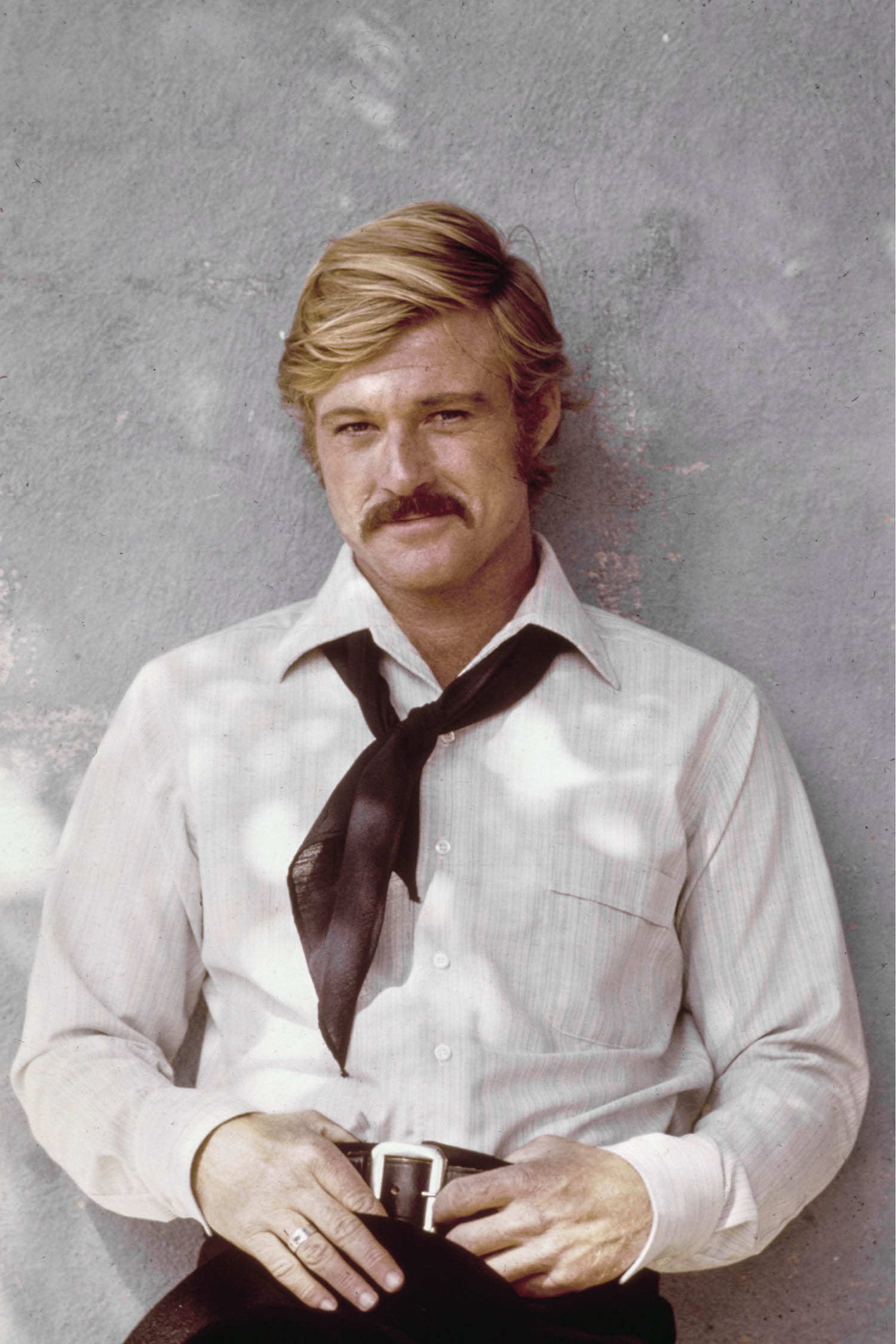

Lean, rangy, with sun-streaked highlights in his cowboy blond hair and a healthy, outdoorsy glow that set off his blue eyes, Robert Redford had archetypal movie star looks. He had the kind of weapons-grade charisma and magnetism that made compelling even his less notable performances in stodgy middlebrow pictures.

But the actor whose early promise was cemented by the massive success of George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in 1969 had a conflicted relationship with celebrity and with the mainstream movie industry that, for several decades at least, couldn’t get enough of him. He distanced himself from Los Angeles and the heart of Hollywood, preferring to live on a homestead in Utah’s mountain country. His idealist’s fervour for film as an art form meant his contribution to cinema went far beyond the movies he starred in and directed. Through his not-for-profit organisation the Sundance Institute, and the Sundance film festival that grew out of it, Redford was a transformative force in an industry he strongly criticised for treating movies “like vacuum cleaners or refrigerators”.

Born 18 August 1936, in Santa Monica, California, Redford spent his early years rebelling against anything and everything. He rejected his religious upbringing and the conservatism of his background: throughout his life, Redford’s politics leant firmly to the left, with a particular focus on environmental issues. Contrary to his family’s hopes, he didn’t acquit himself well academically. At school, he once claimed he was the kind of student who would “climb flagpoles naked for a buck”. He was initially drawn to sports, and attended the University of Colorado on a baseball scholarship, but was kicked out for heavy drinking and never completed his college degree. Redford’s early life was marked by loss. The drinking coincided with the unexpected death of his mother when he was 18; previously he lost an uncle, a father figure who had a major influence on his life, during the second world war.

Untethered from the world of education, Redford toyed with the idea of becoming an artist and travelled to Europe in the hope of awakening his muse. But when he returned to America, he moved to New York, where the hardscrabble authenticity of stage acting fired his enthusiasm for a new career path. A breakout theatre performance came in Neil Simon’s Barefoot In The Park in 1963; he reprised the role opposite Jane Fonda in a 1967 film adaptation that raised his profile.

Breakout role: The actor in 1969’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Weapons-grade charisma: Robert Redford stars in The Sting in 1973

But it was two years later that Redford caught the attention of both the public and the movie industry as the raffish Sundance Kid, opposite Paul Newman’s Butch Cassidy. The film, a wildly successful and bracingly irreverent western comedy, would define Redford’s life and career in several ways. Foremost was the enduring friendship he built with Newman, one based on mutual respect, beer and elaborate pranks.

Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid also whetted Redford’s appetite for doing his own stunts. He later said, “I like the tough stuff. Half the fun of making movies is doing the action scenes. Anyone can say words.” This was an ethos he always embraced: at the age of 77, he delivered one of his finest performances in JC Chandor’s All Is Lost. As a solo yachtsman who finds himself in difficulties following a storm, Redford was effortlessly commanding in a role with virtually no dialogue but numerous physically demanding sequences, almost all of which he performed himself.

Redford’s passions – the outdoors and politics – would frequently inform his film choices. During the filming of the 1974 adaptation of The Great Gatsby, Redford’s co-star Mia Farrow complained that she found it hard to build a connection with Redford because he was so consumed with the unfolding Watergate case that he barely left his trailer. Two years later, Redford not only starred in Alan J Pakula’s propulsive procedural about the case, All The President’s Men, he also served as an executive producer on the project.

It could be viewed as a turning point for Redford – a move away from the escapist pop cinema of films such as The Sting towards weightier themes and more substantial roles. And it perhaps demonstrated to Redford that he could use the power of his stardom to champion the stories that he wanted to see told – something that informed his lifelong support of independent cinema. The choice of the Sundance Institute’s name was no accident: a pioneer at heart, Redford was drawn to the outlaws and the mavericks of indie cinema rather than Hollywood’s cynical money men. His legacy is as much about the nurturing of new careers as it is about his own considerable success.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photographs by Getty Images