In a wood-panelled pub in central Sheffield, surrounded by car lots and high rises, a bald, bearded man is laden with bags. His Sports Direct carrier contains a box: inside is his Emmy, one of eight awarded to the Netflix hit Adolescence, which his company Warp Films developed and co-produced. “It’s surprisingly heavy,” says chief executive Mark Herbert, grinning.

I begin my day with Warp Films – the Sheffield-based film and TV company rewriting the rules for global success – at Fagan’s, a historic drinking hole bought in 2022 by a collective including Herbert and his long-time colleague Niall Shamma (playing bespectacled barman this morning) when its future was threatened. It’s a regular location in their films and hosted their lively post-Emmys homecoming party in September. Herbert posted pictures of the carnage on Instagram, including one of local pal and singer-songwriter Richard Hawley, who introduced Herbert to the pub in the early 00s; another of an Emmy spinning on a turntable as Lauryn Hill’s Doo Wop (That Thing) plays; and one of him and Shamma at the urinals, backs to the camera, their awards held aloft in their free hand.

It was during a Fagan’s Christmas lunch when Herbert – a warm, chatty presence today in the pub’s front room snug – found out Adolescence had been greenlit by Netflix in December 2023. Before that, he wrote on Instagram, “things were bad”. Netflix’s call, which came in “before the Yorkshire puddings”, turned the company’s fortunes around.

What had been bad? “We were developing it elsewhere, we’d got knocked back, and I was worried.” He won’t say who rejected the show initially. “I couldn’t believe we couldn’t make it. I literally couldn’t breathe when I read the script. It was such a wonderful project. I kept thinking, how am I going to tell Steve if it doesn’t happen?” He means Stephen Graham, who won his first lead actor Emmy for his role as bereft father Eddie Miller and gave a speech on behalf of the whole crew when they won another for best limited series. “Whether you were number one on the call sheet or number 101, we were treated equally,” Graham said, after shuffling everybody on stage.

Owen Cooper and Stephen Graham star in Adolescence. Main image: Mark Herbert at Warp Films HQ with his Emmy award

A stunning four-part series about a teenage boy’s terrifying immersion in the manosphere, with each episode shot in one take, Adolescence found instant success. Only a week after its release in March 2025, it was No 1 in 75 of Netflix’s 93 countries. Herbert credits the crew’s “military precision” in getting each episode right and the “bravery” of the actors in two-handed episodes, such as the third, in which Erin Doherty’s steely forensic psychologist attempts to understand Owen Cooper’s defensive, brittle Jamie, a teenager accused of a girl’s murder. Both actors also won Emmys.

Herbert says the ceremony was “brilliant and mad … to be suddenly standing on stage, looking out at Han Solo [Harrison Ford]”. “Holding an Emmy afterwards is quite good for attracting attention as well,” adds Shamma from behind the bar. “Oh, hello, Ted Danson, yes, it’s very nice to meet you.”

But Adolescence wasn’t the only exciting project from Warp Films this year. Three weeks later, it released the ambitious BBC thriller Reunion, about a deaf man released from prison, which incorporated British sign language and innovative sound design (“an absolute revelation” and “a groundbreaking first”, said critics). Then Warp announced a TV adaptation of the cult nuclear apocalypse movie Threads, set in their hometown of Sheffield, which Herbert and Shamma first saw as teenagers. (Herbert was taught by its writer, Barry Hines, at Sheffield university; the idea has been in his notebooks, he says, for many years: “It’s taken 20 years to build up the courage and strength to take it on … it feels like now is the right time”).

Drinks drained, we travel to the office in Park Hill, the regenerated brutalist estate perched on a hill overlooking the city. Herbert gives me a lift there from the pub, putting his Emmy and a Sainsbury’s meal deal in the boot next to his teenage son’s bike, and tells me that their recent success hasn’t come out of nowhere. “It’s not like we’ve suddenly pivoted and done a sci-fi or a superhero thing, and that’s how we’ve won an Emmy – you can follow a line from where we began to this. There’s a DNA running through nearly 25 years that you can see, and that’s the talent.”

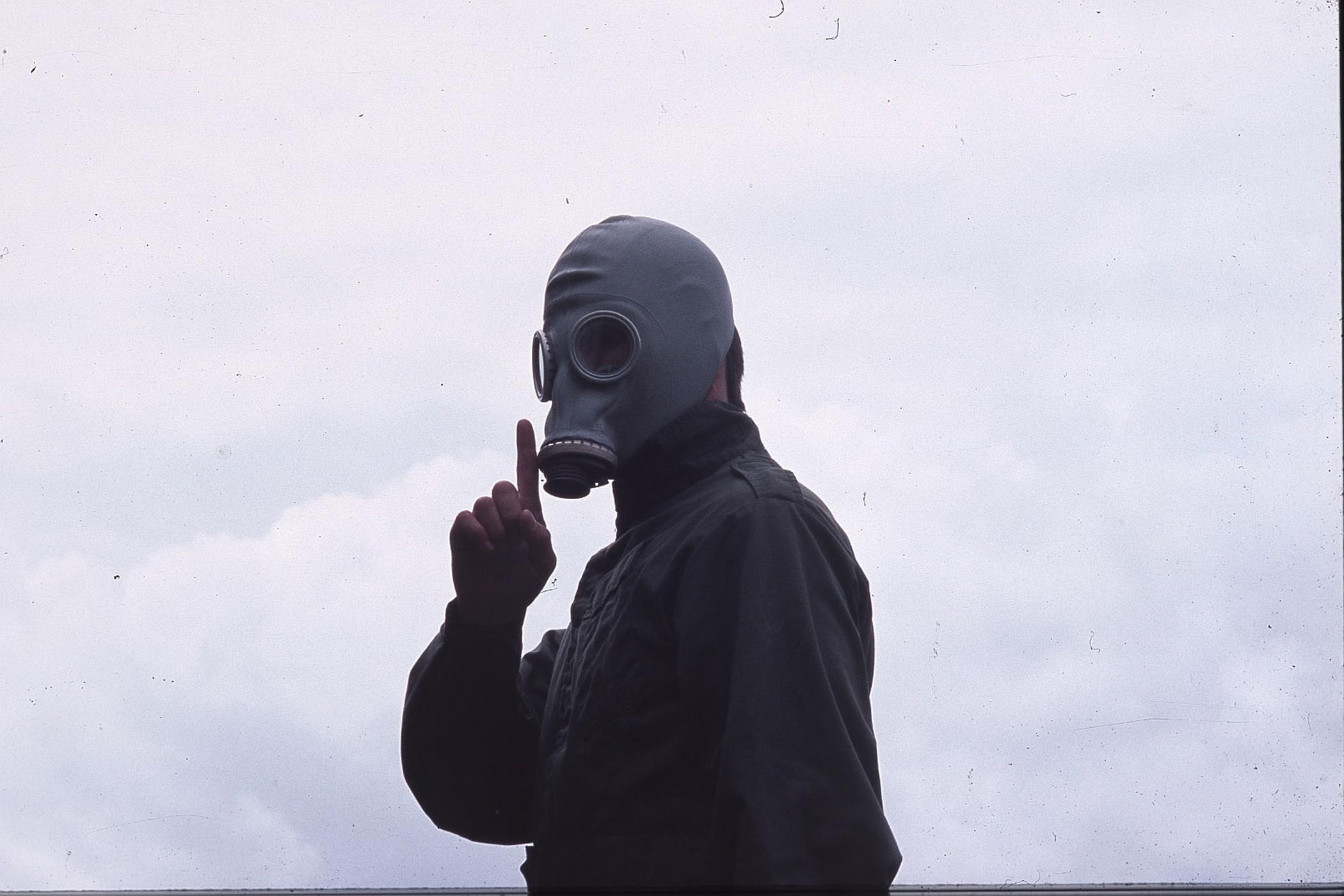

Emily Feller, Niall Shamma and Peter Balm at Warp Films HQ, with props including a gas mask worn in 2004’s Dead Man’s Shoes

Warp Films didn’t begin in Hollywood, but as an offshoot of the Sheffield-based electronic music record label Warp. Founded in 1989, the label released LFO’s techno, Boards of Canada’s ambient and Broadcast’s experimental pop, and commissioned ambitious videos, such as Chris Cunningham’s 10-minute epic for Aphex Twin’s 1999 single Windowlicker.

Moving into film was a dream of Warp’s co-founder, Rob Mitchell, who died from cancer in October 2001, aged 38; he’d also convinced Herbert, a good friend, to leap into TV production after his work as a location manager for 1998’s Little Voice and 1996’s Brassed Off. This move paid off: Herbert’s first producer credit was for the debut series of Peter Kay’s Phoenix Nights.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Weeks after Mitchell’s wake, and after turning down “much bigger” work offers, Herbert met with Mitchell’s co-founder, Steve Beckett, and set up Warp Films in his garden shed. “I remember Rob telling me a few years earlier, just do it. Just do it!” Herbert says. “Warp were big punk rockers, you know – disruptors – and they loved the fact that they disrupted. I felt there was something really important in that.”

Their first outing was Chris Morris’s 12-minute comedy My Wrongs #8245–8249 & 117, about a disturbed man dogsitting for a friend. It won the best short film Bafta in 2002. Its lead actor, Paddy Considine, introduced Herbert to a “frustrated” young director, Shane Meadows. Together, they would make Warp Films’s first full-length feature, the startling 2004 horror film Dead Man’s Shoes. “Paddy and Shane showed me some brilliant short things they’d made, improvising, but said, ‘We can’t do that in the film’,” Herbert recalls. “They thought you’d need a massive crew. We got [now Oscar-nominated cinematographer] Danny Cohen to do handheld camera, a crew that could fit on a minibus, and we made Dead Man’s Shoes in 17 days.” Two years later came the cult classic portrait of 80s Britain, This Is England, then three subsequent miniseries.

Paddy Considine stars in Dead Man’s Shoes

I’m reminded of Dead Man’s Shoes on entry to Warp Films HQ: a figure wearing a boiler suit and a gas mask, just like that of Considine’s revenge-seeking soldier, stands eerily by the stairs. The concrete walls are full of posters for films such as Richard Ayoade’s inventive 2010 comedy Submarine, Peter Strickland’s brain-twisting Berberian Sound Studio (2012), and one film that had many investors asking, Herbert says, “if I was taking the piss”: 2010’s Four Lions.

A blackly comic tale of four hapless jihadis living in Sheffield planning a bomb attack, the film fulfilled several of Warp Films’ missions. “I kept saying [to funders] that pushing boundaries is a big thing for us and so is humanising people, but so many people said, ‘This’ll be the end of Warp Films, the end of your career’.” Four Lions returned £6m on its £2.5m budget, and boosted the profile of actor-director Riz Ahmed and Succession showrunner Jesse Armstrong. The next film, 2011’s Tyrannosaur, gave Olivia Colman her first award-winning dramatic role.

In my two hours at HQ, I meet chief creative officer Emily Feller, who worked on Adolescence with its writer Jack Thorne. Three days after the series went up on Netflix, Feller tells me, she was invited to Downing Street to speak at the women’s equalities committee. Did its impact surprise her? “I don’t think you ever set about trying to tell a story for the whole world,” she says. “You want to tell a story that connects with people, and I think it hit a moment. It was the right time for that conversation.”

On his laptop by the brainstorming blackboard, company director and “rogue southerner” Peter Carlton says he’s working on international business prospects, “contacting Chinese film-makers and talents all over the world”. Warp used to have offices in Sheffield and London, but the latter was shut after the pandemic. “There’s a feel here of slightly chippy outsiders joining together up here. It does sometimes feel like in this industry everybody went to the same school.” Herbert tells me he’s rare among producers for having gone to a comprehensive school; eight of the company’s core staff of 13 are women (including a new female hire, Sheffield-based producer Amy O’Hara from Film4, announced a few days after we meet).

From Four Lions, the 2010 black comedy about jihadis based in Sheffield

As well as Threads (“which is at a very early stage,” Feller says, adding that the “huge names” contacting them to work on the project have been overwhelming), Warp Films’ future slate includes an “AI horror” and “something from the team that brought you Adolescence”, Shamma says. A second season? “Not a second season. But something on that scale, with that ambition.”

Before I leave, I spot a familiar young face at the main table: the actor Fatima Bojang, 18, who played schoolgirl Jade in Adolescence. We walk with her character at the astonishing end of episode two, when the camera is fitted to a drone and flies over to Graham, placing flowers at the site of the murder committed by his son. She’s working on a new project, although she’s not here today for work. “I’m just here to say hello and have a cup of tea because everyone’s lovely,” she says.

Later in the week, an email from the actor Hannah Walters – a producer on Adolescence and Graham’s wife – confirms my theory about Warp Films’ secret ingredient: its tireless support of those it works with. “I refer to Mark as my Obi-Wan Kenobi,” she writes. “His experience and guidance for me as a relative newbie [in producing] has been priceless.” Two days later, Graham sends a voice note from the US where he’s filming an undisclosed project. “I’ve been fortunate enough to collaborate with Warp and especially Mark Herbert for over 20 years,” he says, his voice full of affection. “He always makes you feel like anything is possible. Mark is a man for the underdog, a voice of the people.”

When Herbert sends on these notes, he asks if I can make sure I include their comments about the wider company, not just himself: “I want to reflect the team.” It’s a comment that encapsulates the spirit and humility of Warp Films. I’m reminded of Stephen Graham’s words on the Emmy stage. “We’re all the same, and I think that’s how you get the best work.”

Warp is soon to announce a paid internship scheme supported by Netflix as part of its commitment to creating opportunities in Sheffield and the surrounding areas. Adolescence is available on Netflix and Reunion on BBC iPlayer.

Photographs by Gary Calton for The Observer/Netflix