I had a beautiful life,” you say with a tired smile. It’s a few days before your death and you’re lost in happy memories. Your voice is soft, like a finger gliding along a piece of velvet. You don’t say it to make us happy, or to convince yourself – that isn’t your way.

At first, I don’t understand. Your declaration seems like a dissonant note in an otherwise harmonic chord. For so long now I’ve been worrying about you – years of my life spent living through your pain and misfortune until it became nearly indistinguishable from my own. And yet, here we are.

“I had a beautiful life.”

I’m so glad you see it this way.

You are 58 when you die in 2011. Far too young – and yet we never thought you would make it even that far. Most people assumed you had died years ago. To them, you’re already a figure from the distant past.

After your death, the media thrusts you back into the spotlight. The articles all tell the same story, more or less, cobbled together from the same hackneyed clichés: “erotic actress” and “lost child of the cinema”. They write about Last Tango in Paris and of your “ruined career” and “tragic destiny”. There’s the hedonism of the 1970s, the cruelty of the film business and, of course, the sex and drugs.

No one writes about how, when you die, you are sipping champagne, your favourite drink – the one that could make you forget your childhood and help fill in the cracks of a fractured, sensitive soul. You leave us amid bubbles and bursts of laughter, loving faces and smiles – upright with your head held high, a little tipsy. With panache.

Schneider with Marlon Brando in Last Tango in Paris

For decades you refused to speak about Tango. Whenever the movie was mentioned, you froze. In an interview in 1983, more than 10 years after the film was released, you implored the journalist, your hands clasped in prayer: “No, please. I don’t want to talk about that film.” You were there to speak about your role in Luigi Comencini’s The Imposter, but this film clearly didn’t pique her curiosity. You nicely insisted, without getting angry, and you spoke slowly, choosing your words carefully. “I’m always linked to it. Everywhere I go, I have Tango with me. Enough is enough.” You tried to explain: “I did films before it. I would have done things regardless.”

I’m not sure you believed this yourself – that you would have had a film career if not for Tango. But you repeated it often, as if you longed to make it an incontrovertible fact. Tactfully, you attempted to find a way out of the conversation. “I prefer that we speak about The Passenger. This film is closer to me.” The journalist didn’t respond. You were no longer of interest to her.

You hesitated to do the film at first, as you later admitted, since you “didn’t totally understand the script”, though you did recognise that it was audacious and daring. Your agent swept away your reservations. “You can’t refuse a leading role opposite Marlon Brando!”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

You were 19 years old, about to embark on the most scandalous role of the 1970s. Your mother had to sign a waiver so you could accept the part. The first time you meet Marlon Brando is on the Pont de Passy just as you’re about to shoot a scene. You find it funny that he’s wearing lifts in his shoes and think, ‘Oh, he’s not as big as all that.’ You’re ready to do your job, afraid of nothing.

Your first scenes are with Jean-Pierre Léaud (the favoured actor of François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard), who plays your fiancé. Bertolucci didn’t want to put you face-to-face with the icon right away, fearing you would be intimidated. Unexpectedly, however, Brando is there. You perceive a childlike sweetness in him as he tries to put you at ease. The first question he asks is what zodiac sign you are. “Aries,” you tell him. “Me too,” he says. “Rising?” “Libra.” “We’ll get along just fine,” he says, “which is good, because I believe we have a few intimate scenes …”

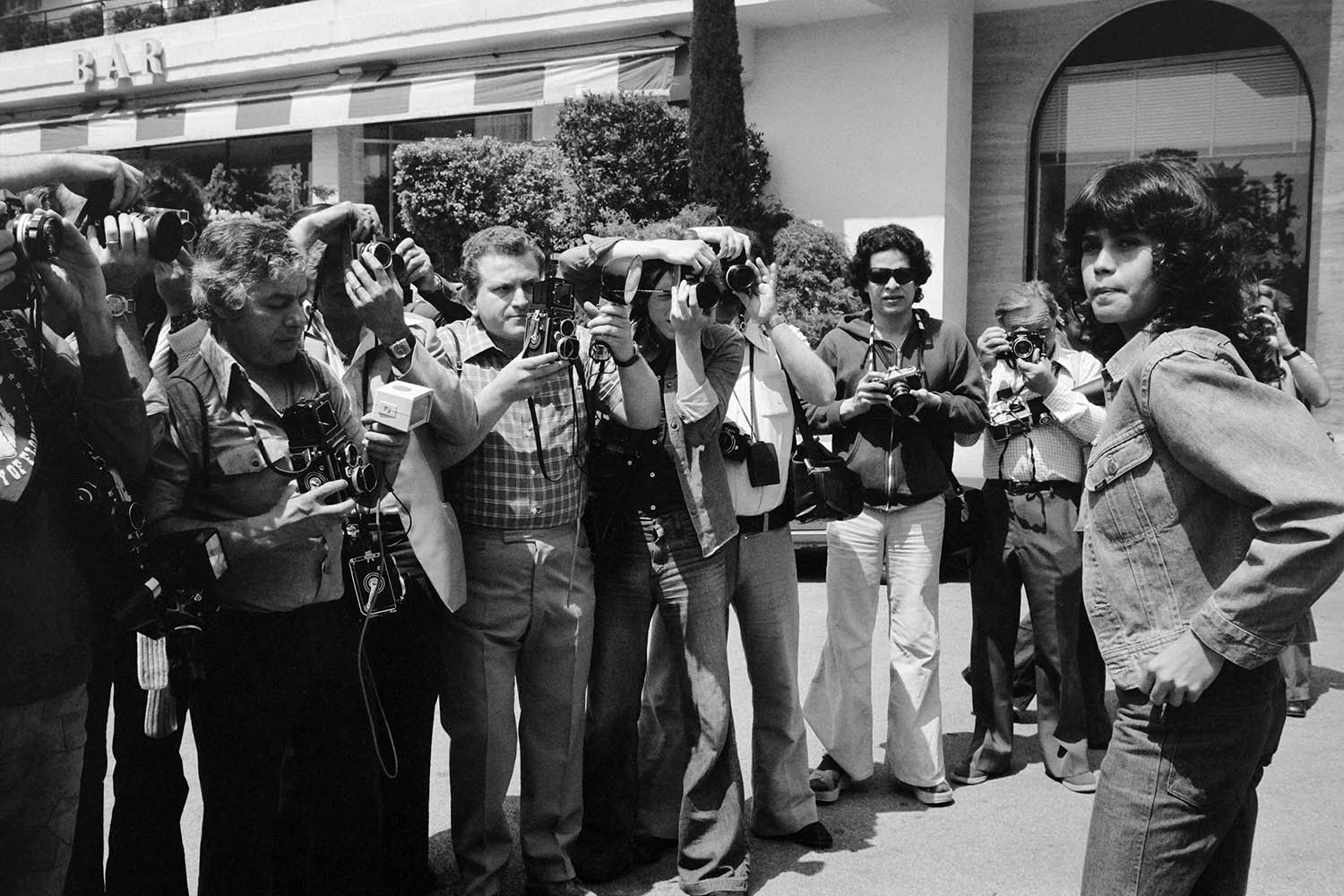

Schneider at the Cannes film festival in 1975

He gives you a kiss on the cheek as a father would give to his daughter. Your first real scene of the shoot takes place in a bed. Any doubt about the nature of the film is extinguished immediately. For the sex scenes, or any scenes with nudity, Brando requests a closed set and Bertolucci complies, making the set off-limits to anyone not directly involved with the film. Photographers and other onlookers wait outside every day for the actors to appear. Some even rent apartments across the street, hoping to get a shot. Only the curious and stubborn Jeanne Moreau manages to break through the barricade. Throughout Paris, rumours spread that the Italian director is making something risky and disturbing.

Brando imposes rules and conditions for everyone involved with the film. He does away with the rigid hierarchy common to film production. It’s out of the question for him that the crew should eat less well than the actors. During the breaks, he offers drinks and sandwiches to everyone, paid for out of his own pocket. “He respected people,” you say later. “No matter how big or small. I’ll always remember him as a generous and genuine man.”

Brando goes back to his hotel every day at 6pm and refuses to work on the weekends. Bertolucci doesn’t object. For you, however, there is no such reprieve. You film take after take until after midnight, and on Saturdays you film your scenes with Léaud. It’s more brutal than a marathon. By the end of the 15-week shoot you’re drained and exhausted, and you’ve lost 22 pounds. The crew often find you in tears. Some try to comfort you with a word or a look; others say nothing, pretending not to notice. She’s lucky, this little unknown, sharing the screen with the great Brando … She doesn’t get to complain. Only once do you dare protest to the director: it’s too much filming, 14 hours a day, every day. You later tell me that Bertolucci responded without even looking you in the eye. “You’re nothing. I discovered you. Go fuck yourself.”

With Jack Nicholson in The Passenger (1975), a film she preferred to talk about

One morning, Bertolucci takes Brando aside and suggests a scene that isn’t in the script. The men agree that nothing should be said to tip you off – that it’s better if you are taken by surprise. Did you sense a particular atmosphere on the set that day, complicit looks between the director, actor, and crew? Or were you too tired by that point to question anything? Who thought of the butter? Was it Brando, as Bertolucci claims, or Bertolucci, as Brando insists?

Rolling, action … You and Brando are lying on the floor, dressed. Suddenly, Brando turns you over, roughly pulls down your jeans and, grasping a mound of butter in his hand, he shoves it between your legs while thrusting his pelvis against you. You fight, you scream and cry. It’s impossible to escape; Brando’s body is pinning you to the floor. Bertolucci keeps the camera trained on your anger and terror. There’s only one take. Afterwards, Bertolucci says, “C’est bon.” That’s good. It doesn’t last long, but for you it’s an eternity. Brando releases his grip and you scramble up, staring at the two of them with murderous rage. In your fury, you destroy the set: tear down the drapes, shatter a vase, a lamp; anything you can get your hands on, you smash on to the wooden floor. After, you go to your dressing room and remain prostrate for hours. The director couldn’t care less; he got what he wanted. He couldn’t have dreamed of better. “She raged against me, against Marlon, against all men,” Bertolucci would comment years later, remembering the scene.

You come out of the filming shattered, sensing this one scene has marked you for ever, like a bad tattoo you’ll spend the rest of your life trying to cover up. It doesn’t matter that the sodomy was simulated – it makes you feel dirty and violated. You don’t understand that you could’ve prevented this scene from appearing in the film since it wasn’t in the script that you had agreed to. You could have called a lawyer, filed a suit against the producers, and made Bertolucci cut it, but you’re young, alone, and poorly counselled. You know nothing yet about the rules of the film world. The perfect victim.

This scene becomes your cross to bear. For your entire life you will have to endure unsavoury jokes and cruel pranks. Once, in a restaurant, a waiter asks with an obnoxious wink if you’d like some butter. On an airplane, a flight attendant puts a pat of butter on your plate when you haven’t asked for any. Without your permission, a dairy manufacturer puts your picture on their labels. In Rome, where you are filming René Clément’s Wanted: Babysitter, you’re insulted on the street. More than once you are physically attacked. Faced with this incredible psychological violence, you hide your pain behind a forced laugh and respond with a quip: “I only cook with olive oil.”

On set with Bernardo Bertolucci, the director of Last Tango in Paris, in 1972

You are not yet 30 when you overdose and are committed to the Sainte-Anne sanitarium, where addicts are sent when going through withdrawal or suffering dementia. Patients are put in straitjackets and knocked out with high doses of medication. Some are given electroshock therapy. The families all know the drill. They navigate the maze of white corridors by rote under the fluorescent lights, trying to ignore the anguished cries escaping the rooms. They know the names of all the nurses; they know the medications and their doses. By this time, you’re shooting four grams of heroin a day, and have become a regular here. Your fame lends you VIP status. You receive a blood transfusion, a treatment that apparently is only ever administered to American celebrities near death.

On the morning of your death, the newspaper Libération prints a big, bare-chested photo of you obviously pulled from Tango. With your naked breasts on display, you appear as a carnal, sexual object. You had spent most of your life trying to erase this indelible mark, and you would have hated this kind of homage. It would have enraged you and made you cry. We didn’t like this representation of you either, seeing you reduced to your flesh, because there is so much more to you than your exposed body, because the deceased should not be represented in such a way, because a newspaper would never dare to accompany the obituary of a man with a naked image of him.

The scene from Tango is always in the periphery, waiting. Even in 2016 as I write about you, I see a photo while scrolling through my Twitter feed. The American version of Elle has exhumed a video of Bertolucci at the Cinémathèque Française in Paris in 2013. The director is relaxed as he explains himself. “The scene with the butter was an idea that I had with Brando the morning of the filming.” He confesses that he felt “horrible” about the way it made you feel, but still, he justifies the decision. “I wanted her to respond like a girl, not an actress.” Regardless of the guilt he says he feels, he regrets nothing. “I wanted her to feel humiliated,” he says. “To get something real, you have to be completely free. I didn’t want Maria to play at the anger and humiliation, I wanted her to feel it. She hated me for the rest of her life for it.”

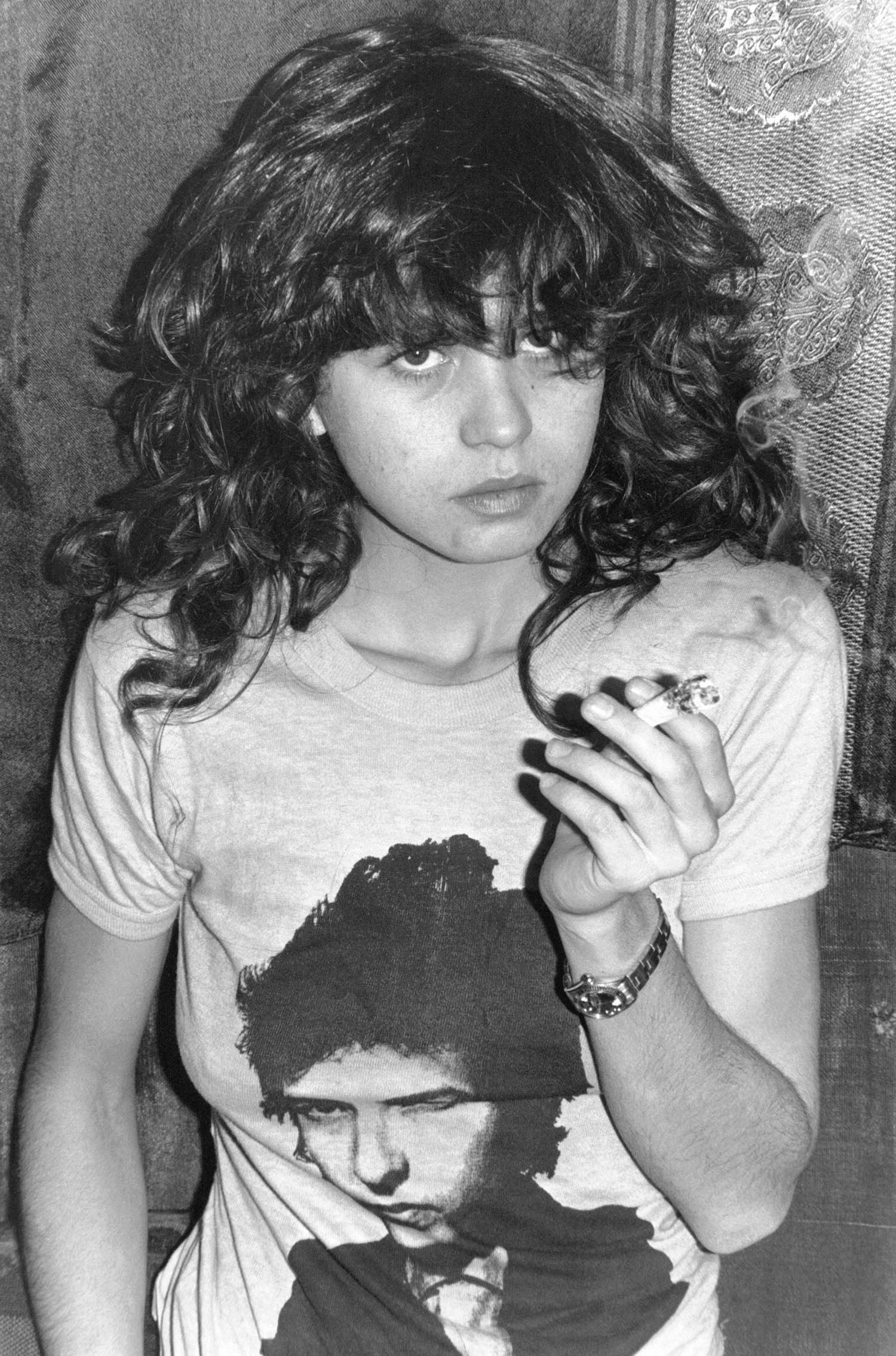

Schneider in 1978 – ‘She raged against me, Marlon, all men,’ Bertolucci said

Art before everything. To him, you were merely collateral damage. It’s what you’d been saying all along, but you may as well have been shouting into the void. No one wanted to hear it. In 2013 not much was thought of the filmmaker’s comment. When the interview resurfaces in 2016, it ignites the web. The New Yorker and the Guardian pick it up after Elle. Then Vanity Fair and the Spanish, Latin American and Italian media. The hour has come to denounce the culprits and bring the 1970s, when abuse was tolerated under the guise of sexual liberation, to task. Le Parisien reprints the article from American Elle: “In Last Tango in Paris, Bertolucci and Brando planned the rape of Maria Schneider.” The polemic spreads on Twitter, in all languages and on all continents. The American actor Jessica Chastain types a ferocious post: “To all the people that love this film – you’re watching a 19-year-old get raped by a 48-year-old man. The director planned her attack. I feel sick.” It’s retweeted tens of thousands of times.

Facing the onslaught, Bertolucci decides to end his silence, beginning with this disturbing sentence: “I would like for the last time to clear up a ridiculous misunderstanding regarding Last Tango in Paris, which continues to be reported around the world.” Not wanting to go back on his last remarks, he stitches a new version together. “Several years ago at the Cinémathèque Française someone asked me for details on the famous butter scene. I specified, but perhaps I was not clear, that I decided with Marlon Brando not to inform Maria that we would use butter. We wanted her spontaneous reaction to that improper use [of the butter]. That is where the misunderstanding lies. Somebody thought, and thinks, that Maria had not been informed about the violence on her. That is false!” He continues. “Maria knew everything because she had read the script, where it was all described. The only novelty was the idea of the butter. And that, as I learned many years later, offended Maria. Not the violence that she is subjected to in the scene, which was written in the screenplay.”

He’s lying, but you are no longer here to give your version. The early decades of the 21st century will be a time of moral reckoning. The victims are heard, and aggressors are pilloried in the media. I see an article about the culture of rape in the film industry. To illustrate, there’s the photo of Brando on your back while you fight to get away. From then on, Bertolucci will have trouble securing financing for his films. Until his death in 2018, he will continue to defend himself in order to preserve his image and films for posterity. But his career as he knew it, is finished. You might have been satisfied to see him facing such public derision – this man who had so terrorised you and is still contradicting himself all these years later. Maybe you wouldn’t even have bothered to comment, content to just smile, with that wry, knowing expression of yours.

My Cousin Maria Schneider by Vanessa Schneider, translated from French by Molly Ringwald, is published on 3 July by Little, Brown

Photographs by Bettman Archive, Raph Gatti/ AFP, Getty, Alain Dejean/Sygma, Getty, Jean-Jacques Lapeyronnie/Gamma-Rapho, Getty