Studio Ghibli, cinema’s most unexpected global hit machine, turned 40 this summer. The animation house’s two surviving founders, Hayao Miyazaki and Toshio Suzuki, seem to have abandoned dreams of finding successors. But could Ghibli survive without them?

Ghibli films are not like other movies, and not just because they are the last bastion of hand-drawn animation. It’s the rules they break. Take My Neighbour Totoro, created by lapsed Marxist Miyazaki and released in 1988. Themed around animism and Shinto symbols, it has a loose plot about two girls meeting a large fluffy woodland spirit. The renowned US film critic Roger Ebert described it as, “a film with no villains. No fight scenes. No evil adults. No scary monsters.”

In 2022 the Royal Shakespeare Company’s star-free stage version – now playing in the West End – became the fastest-selling show in the history of the Barbican theatre’s box office, beating Benedict Cumberbatch in Hamlet and Cate Blanchett in The Seagull. This is Ghibli’s mysterious power. It has managed to become a global phenomenon using a strategy that can best be described as aggressively uncommercial.

Ghibli was formed in 1985 by Miyazaki, producer Suzuki and fellow animator Isao Takahata. The founders have a wary attitude to interviews. Takahata died in 2018, leaving Miyazaki, who almost never meets the press, and Suzuki, who does a little publicity.

I was granted an audience with Suzuki when he passed through the UK recently. He is in London very briefly, I was told, so could I be at the hotel before 7am? He comes down wearing a loose-fitting garment and traditional sandals, and the translator says that he has a Eurostar to catch so we can talk while he has breakfast.

“The founding and the philosophy of Ghibli has a lot to do with us being the postwar generation after Japan lost the war,” Suzuki, 76, says while nibbling fruit. “We hated the Japan of the war. Afterwards, Japanese society looked to America for inspiration and guidance, and Miyazaki hated Japan even more for that. He felt neither Japanese nor American and he turned to Europe and that western influence. Europe and the UK are like Japan, in the way we have got old history. And so that has helped him with his pictures.”

Ghibli’s philosophy and style evolved long before the studio was founded, Suzuki says. He got to know Takahata and Miyazaki just after they had finished adapting Johanna Spyri’s Heidi novels into the kids’ cartoon Heidi, Girl of the Alps for Fuji TV in the 1970s. “Heidi contained many of the themes that films like Totoro have,” he says. “The power of nature; the contrast between the wealthy and the simple life.”

Toshio Suzuki: ‘Our philosophy was to make films that are fun to watch, include a message and make money’

After the failure of Miyazaki’s movie debut, Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro, based on Maurice Leblanc’s gentleman thief Arsène Lupin, Suzuki hired him to draw for his anime comic Animage; then the trio founded Ghibli, naming it after an Italian second world war plane, which in turn took its name from a hot desert wind.

“Takahata was the philosopher who understood the politics,” Suzuki explains. “He instilled themes into our work, but the person who was good at expressing them in pictures was Miyazaki. So we decided the studio should have a philosophy with three purposes. One, to make films that are fun to watch. Two, that we include a kind of message in each film. And three, in order to be able to continue on to the next film, each film has to make money.”

Global domination, however, has never been part of the studio’s plan, says Justin Johnson, head of cinema programming at the British Film Institute. “Ghibli almost seems to be unconcerned with its reach outside Japan. It makes films for its home markets, and if they resonate and work outside, that’s brilliant, but that’s not what they’re designed to do. You couldn’t imagine a less commercial film than The Boy and the Heron [2023]. It follows none of the structure of western movies but it was huge and award-winning.”

Ghibli’s attitude to marketing is unusual. It operates a theme park and museum outside Tokyo: both require dedication to visit. “I literally had to get somebody who lived in Japan to go to a supermarket and book tickets seven months in advance,” says Johnson. “It puts every barrier up to stop you. Studio Ghibli is huge in this country and the US. If you had a Studio Ghibli shop in the UK, you’d clean up. But even in Japan, there’s hardly any merchandise. When I went to the museum, I came back with as much as I could – bags full of stuff.”

This resistance to success extends throughout the company. Harvey Weinstein, overseeing the US release of Princess Mononoke for Disney in 1999, suggested that American audiences might find a two-hour-plus Japanese animation a little too long; Suzuki sent the now disgraced film producer a samurai sword with a note saying: “no cuts”. When the New York Times wanted to write a big feature on Ghibli’s theme park, the PR team wasn’t sure. “They said,” the reporter wrote, “that it might make more people want to come and visit. This struck them as a problem.”

Ghibli Park, which I visited last year, has no security checkpoint, no ticket booths, no ambient soundtrack, no giant statues of animated characters and no rides. Most of the park is open to everyone for free, except for sections called things such as Hill of Youth, Dondoko Forest, the Valley of Witches and Mononoke Village. Within these zones are full-size recreations of houses, castles, shops and streets from famous films. Sitting in a recreation of the house at the heart of My Neighbour Totoro, it was staggering to open drawers and find the entire accoutrements of life – pencils, toys, bedding, clothes – that are changed seasonally. The stove works and the water runs. But there are no characters and no action.

My Neighbour Totoro on stage in London

That matches Ghibli’s on-screen style. The studio leans into quiet, contemplative scenes with meticulously animated characters, almost always hand-drawn with a hint of Franco-Belgian artists such as Tintin’s Hergé, Lucky Luke’s Morris and Blueberry’s Moebius.

It’s so distinctive that when ChatGPT released a flood of Studio Ghibli-inspired pictures to show off its new image generator, the move was largely met with fury – and yet fans nevertheless used the chatbot to create their own images, loathing themselves as they did.

“People describe Ghibli as anime but that isn’t right,” says Michael Leader, co-host of the Ghibliotheque podcast. “Miyazaki and Takahata pre-exist that term. They’ve been working in Japanese animation from the 1960s, so they pre-date anime. Miyazaki encapsulates so much of what Japanese animation is, how it developed and how it became an artist’s medium.”

Originally the duo worked for Tokyo studio Toei Doga, which had ambitions to become the Disney of the east. Both artists were Marxists and their trade union activism developed there, with Miyazaki leading walkouts as general secretary. In the 1970s, they worked on adapting European children’s fiction for teatime telly in Japan and visited the original story settings to get a feel for the locations.

“This all informs the worlds they create, even in a fantasy film such as Castle in the Sky, which is inspired by the miners’ strike,” says Leader about one of the more unlikely sources of inspiration for a Ghibli movie. Miyazaki’s visits to Wales, with its striking miners, in 1984 and in 1985 became the basis for the 1986 film. The village at its heart is drawn with rows of terraced houses like the mining towns in the Rhondda valley – with no echo of Japanese architecture – and the burly miners who come to the rescue of the heroes Pazu and Sheeta are based on the striking miners he met.

“I admired those men,” Miyazaki said in a 2005 interview. “I admired the way they battled to save their way of life, just as the coalminers in Japan did. Many people of my generation see the miners as a symbol, a dying breed of fighting men. Now they are gone.”

And while many of Ghibli’s stories play with tales from Japanese myth, the books Miyazaki has adapted include two by the Welsh author Diana Wynne Jones: Howl’s Moving Castle, which plays out in a valley kingdom inhabited by wizards, fire demons and undulating shadow monsters in natty straw boaters; and Earwig and the Witch, in which an orphan is adopted by the eponymous witch.

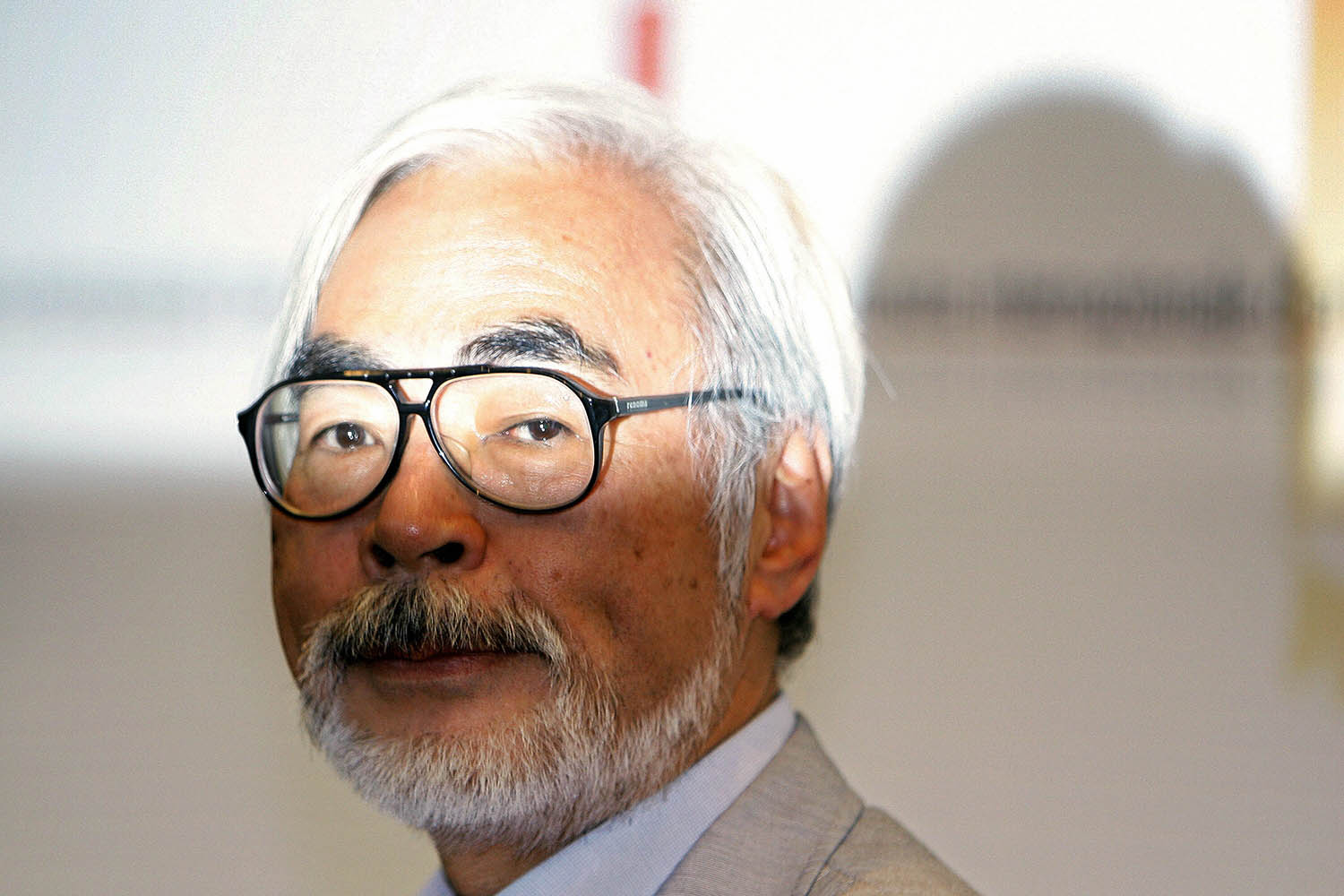

Hayao Miyazaki: ‘I admire the way the miners in Wales battled to save their way of life, just as miners in Japan did’

“Diana Wynne Jones made a very interesting observation about Miyazaki,” says Leader. “She said she and he were the generation who grew up in the shadow of bullets. The fantasy writers of that generation have war at their heart, often pushed to the sidelines in a subtext conflict, whereas Miyazaki likes to have his cake and eat it. He’s a pacifist who loves the machines of war. He has an innate, maybe generational talent, for drawing planes and tanks.”

Anime author Helen McCarthy has written that Miyazaki’s work, from his early television animations to Princess Mononoke, begins with an attempt to find the pacifist hero in an action genre. In Princess Mononoke, he finally manages this in Ashitaka, who struggles to stop a war between forest spirits and the guns of Irontown.

After Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki’s films become increasingly autobiographical. The Boy and the Heron deals with both of his recurrent traumas. Born in 1941, he saw Japanese cities bombed, and grew up in the aftermath of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 80 years ago this month. But he also had to deal with the guilt of his father’s factory making parts for the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter plane. Meanwhile, his mother, Yoshiko, suffered from spinal tuberculosis. The film involves a troubled child, Mahito, who is sucked into a fantasy realm after the death of his mother and the marriage of his factory-owning father to his aunt.

“Miyazaki felt very protective of his mother,” says Japanese-born psychologist Dr Ryota Kishi. “And I see his films having an underlying self-hate, underlying repentance, guilt, shame; all those things that a nation that is not traditionally open to talking about healing is still dealing with. That’s why some of us really get into a sort of therapeutic space while watching these films.”

Miyazaki’s mother and her illness appear regularly in his movies, according to Suzuki. In Totoro, the reason the family heads to the country where they meet Totoro is because the mother is in hospital. “That’s his own mother,” says Suzuki, explaining that she spent nearly eight years in and out of hospital with spinal tuberculosis. “She is why he really wanted to portray women in film rather than men,” Suzuki adds. “He is more interested in women.”

Ghibli films have a complicated relationship with women. About half the films have female leads, but they are at times idealised in their innocence and purity. The only western works Ghibli has adapted have been by female writers: Wynne Jones, Mary Norton (The Borrowers), Joan G Robinson (whose book When Marnie was There was the source for Ghibli’s eponymous 2015 Oscar nominee) and Ursula K Le Guin, author of the feminist Earthsea fantasy series.

A model of No-Face from Spirited Away at Ghibli Park

“The fact that it chose Le Guin is hugely significant,” says Phelim McDermott, co-founder of the Improbable theatre company, who directed Totoro for the RSC. “What you see in her books is a kind of stealth archaeology of her own internalised patriarchy and the way that she solves that problem. Ghibli is not overtly political, but for me, it is massively so, because of how it holds questions rather than stating answers. Totoro deals with ecological issues but gives people space to find their own sense within them.

“A good children’s story keeps speaking to us as we get older. [The films of] Miyazaki and Suzuki are like little ghost roles in our conversation, creating a kind of deep democracy within us.”

Forty years after its birth, Ghibli has never been so successful. But, true to form, it is on the edge of wrecking that success. Miyazaki is 84 and has retired at least three times. Like a grouchy Willy Wonka, he shuts down the studio and sends everybody home for good, then grinds it back into life for reasons he never makes clear. A harsh, exacting boss, he is irascible to the point of rudeness, dismissing other animators’ work, including that of his own son Goro. In the documentary How Ponyo Was Born, director Kaku Arakawa captures Miyazaki fidgeting and taking a cigarette break during the first screening of Goro’s debut, Tales from Earthsea. When asked afterwards what he thought of the film, Miyazaki replies: “I saw my own child. He hasn’t become an adult. That’s all. It’s good that he made one movie. With that, he should stop.”

Miyazaki also insists on hand-drawn animation, dismissing AI as “an insult to life itself”. All of which makes him frustratingly irreplaceable. In 2023, Ghibli was sold to Nippon TV, in part because succession planning for Miyazaki proved impossible. Goro, unsurprisingly, declined to take on his father’s role as head of the studio. At a lunch in Tokyo last year, Nippon TV executives said to The Observer that they planned more theatrical adaptations, tour exhibitions, and wanted to expand the screening and streaming of existing films. They had no intention of replacing Suzuki or Miyazaki, which is probably for the best.

“Miyazaki is a generational talent but so much of the context around him allowed him to do what he did,” says Leader. “There’ll be no other Steven Spielberg, because what he created in the seven-year period from Jaws to ET can’t be replicated. It’s the same with Paul McCartney, [Mick] Jagger and [Keith] Richards. When they go, that’s the end of the spirit they captured and embodied. As somebody who’s very invested in these films, it feels appropriate to see Miyazaki’s passing as the end of the story.”

As a founding talent of Ghibli, Suzuki’s legacy, too, is assured. “After we are gone, I don’t know what’s going to happen,” he says amiably over breakfast. “But that will be something for other people to work out.”

The remastered 4K Princess Mononoke is screening at the BFI Imax. The RSC production of My Neighbour Totoro is at London’s Gillian Lynne theatre

•

This article was amended on 22 August 2025 to include information about Joan G Robinson

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photographs by Yuichi Yamazaki, Getty Images, RSC