Portrait by Maria Spann

Fran Lebowitz is angry with me on sight. I am waiting in a room just off the main bar of the Chelsea hotel.

“I was looking in there for you,” she says, irked, as she sits down.

“I’m sorry,” I say. “There was construction above the other room so it was a bit noisy.”

“I can’t hear you,” she says.

“I said: ‘I’m sorry, there was construction in the other room, so ... ’”

“There’s nowhere in New York there isn’t construction. Impossible.”

Lebowitz, who once described herself as “the designated New Yorker”, has made a career and a life out of sweeping statements about the city, some of them practically aphorisms, impossibly general but acutely insightful too. This is a fitting balance for New York, a place that is burdened with bland, schmaltzy, romanticised tourist board representations of itself, but that also is as unique as they say.

Related articles:

Lebowitz, 74, whose signature uniform of Anderson & Sheppard blazer, blue denim and boots has been lauded by Vogue, makes for an easily recognisable icon, a consummate walker like any true New Yorker, often stopped for selfies by fans. I saw her by chance several times before this interview, once smoking in the West Village and once at a Paris Review gala, where I looked admiringly upon her ability to stroll between tables of millionaires and beloved literary stars unperturbed while I cowered by the bar, afraid my country mouse origins were apparent to all.

I ask if she minds being stopped and approached so often, being a public emblem of the city.

“It doesn’t bother me if I’m standing still. Sometimes, I’ll be in the middle of the street crossing Fifth Avenue and someone coming across stops and says: ‘Can I just ask you?’ ‘Yes, but you have to come on to the sidewalk. Because here come a million cars.’ And I don’t like it if I’m going down the stairs to get to the subway as someone’s coming up, because then I’m going to miss the train.”

Warming to her theme, she shifts happily in her seat, as she does when she has a good, kvetchy story.

“Lately, this kid comes into the subway – he had seen this video I made in a museum about a Rembrandt. He goes: ‘I can’t believe I’m seeing you. I just saw that video you made about your Rembrandt.’ I said: ‘It’s not my Rembrandt.’ ‘You said it was your Rembrandt,’ he goes. I said: ‘I certainly did not. Let me just explain something. There are two kinds of people in the world. The kind of people who own Rembrandts and the kind of people who are racing to get the F train, and they are never the same people, OK? And there are many, many more people riding the F train than have their own Rembrandt.’”

Lebowitz has a somewhat singular career for the current age; there are few people in today’s culture allowed to be professional wags. She came to fame as a writer, with columns in Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, among others, and two collections of comedic essays. There was a novel long rumoured that has yet to make an appearance.

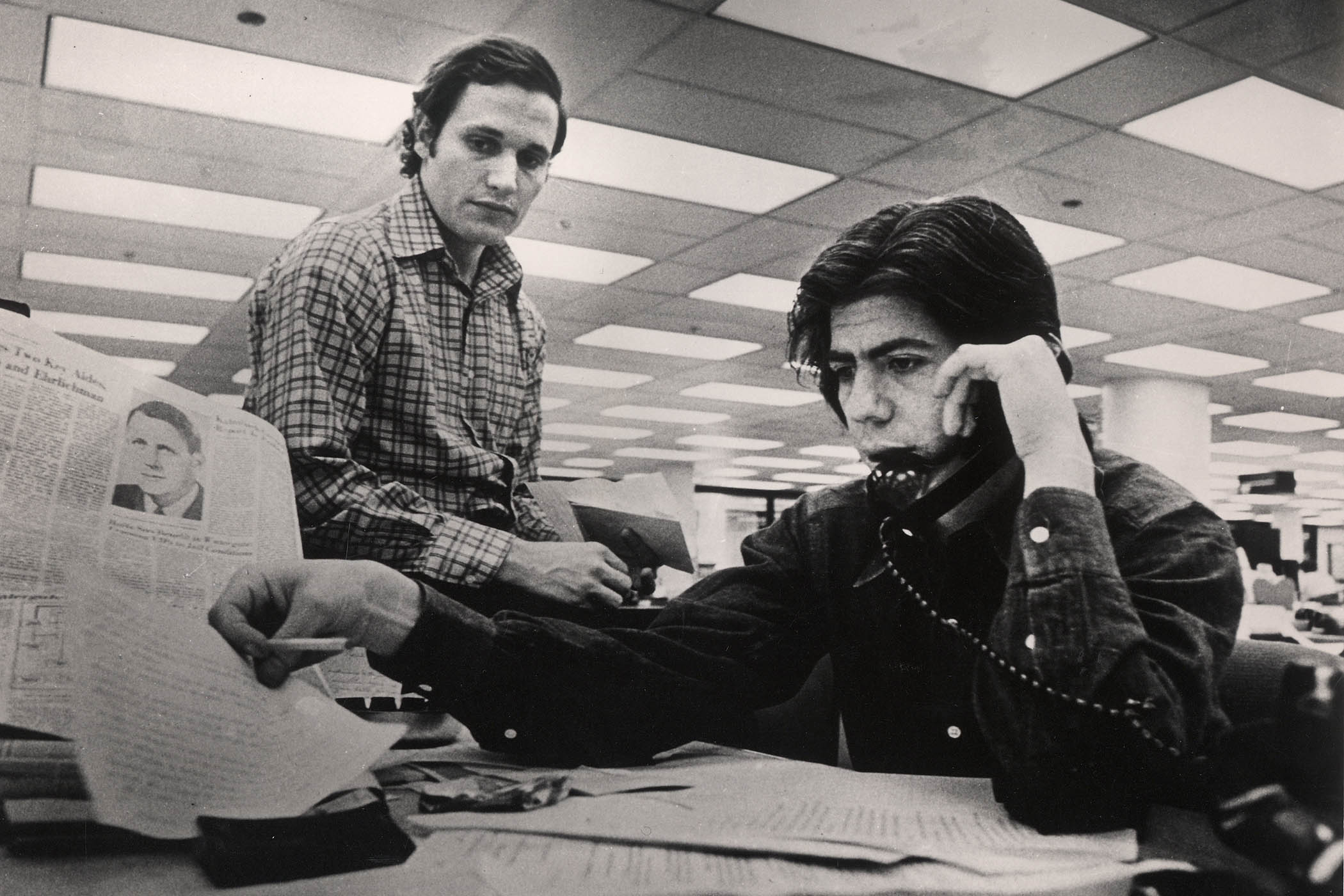

Fran Lebowitz and Andy Warhol at a New York party in 1977

Primarily, though, she makes her living as a wit, as a bearer of bon mots, and as the poster girl for a certain kind of crusty but erudite and essentially good-natured New York archetype, intellectual and judgmental, and walking the line between rudeness and frankness with engaging grace. Martin Scorsese has made two films of her walking through the city and delivering talks, a feature called Public Speaking and a Netflix series named Pretend It’s a City.

We are meeting in advance of a UK run of September shows, including one in London at the Barbican centre, and I ask what her relationship to that city is.

“I went to London once in the summer and I remember two things. It was during Wimbledon, so there were a million people I know, who, unbeknownst to me, leave my country once a year for a tennis game. And it was the Fourth of July, and my UK tour manager asked me: ‘Do you usually do something special on the Fourth of July?’ I said: ‘Yes, we celebrate our victory over you.’ But now, of course, no sane American is celebrating anything.”

I tell her that since moving to New York, people at home will sometimes ask me how I can live in the US and that all my native New Yorker friends will reassure me that I have no idea because New York is not the US.

“Oh, you live here?” she says, and I believe I can see her like me a sliver more. “Well, that’s right, New York is not America. America could be more like New York. And in fact New York should now try to be more like New York. A lot of my friends have never been to America. I have friends who have been 50 times to Cambodia, to Vietnam … have you ever been to Kansas?”

I ask what she makes of the recent unprecedented victory in the Democratic mayoral primaries for socialist candidate Zohran Mamdani – I read in the New York Times before voting day that Lebowitz considered herself too old to vote for anyone so far to the left.

“Well, now I will, because I can’t vote for [Andrew] Cuomo. I don’t know him [Mamdani], and perhaps he really thinks these things. A lot of young people do. I felt such things, but I wasn’t as old as he is. I stopped thinking that kind of stuff when I was 20 – around the time I got old enough to realise the thing about socialism is that the ideas are delightful, but the human species is not good enough for it. The human being is a horrible species, and so it always results in something horrible, not because the ideas aren’t nice, but because it doesn’t work. So he may really think these things, but he certainly can’t do them.”

But you’re willing to vote for him?

“Yes. In a way, it’s a very good thing that happened, I think, because I’m dying to get rid of old blood. And I’m old. So, you know, I’m 74. I think: ‘Let’s get rid of these old people’ – imagine what people who are 20 think. And it seems like a reaction against Trump, which is good, because the Democrats in office do nothing.”

I have always liked taking the subway, partly because I am susceptible to all the New York romanticism I would prefer to be above; partly because I rarely have an office to go to so don’t have to ride it in rush hour; and partly because once, while stoned on the Q train, I saw a man wearing two enormous snakes around his shoulders and he allowed me to touch them slowly for the 20-minute journey, which felt at the time like a profoundly spiritual experience.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The subway, however, has become something of a symbol of the rise in crime post-Covid, a time when many social contracts dissolved or were revealed never to have existed. In recent years, crime on the subway has been trumpeted so loudly that tourists will post photos from it, proud to have braved the trip. There was a dreadful killing on F train in 2023 in which Daniel Penny subdued a mentally ill Black man named Jordan Neely who was behaving erratically and threatening passengers; Penny put Neely in a chokehold and killed him. Penny, a former marine, was later cleared of all charges and subsequently invited by Donald Trump to join him at an army-navy football game.

I ask Lebowitz, who has spoken often of the pleasure in people-watching on transit, if her relationship to the subway has changed at all.

“I ride the subway. Not because it’s delightful. It’s horrible. I have friends who yell at me because it’s dangerous, but here’s the thing. I work too hard to burn my money, because nowadays you catch a taxi, you open the door and it’s $40 – you put your foot in, it’s $45. It’s not worth it. The subways are no more dangerous than being in the street, and I’m not going to stop doing that either. There was a period where there were a lot of people being thrown into the tracks; this is the thing people were yelling at me about, and I said to them, and this is the truth: ‘I am pasted against that wall. I am like the young Muhammad Ali against that wall.’”

Money is an interesting subject for Lebowitz; she claims to be disturbed by the gauche transparency with which younger people discuss finances (“One thing we never, ever talked about when I was young was money – it was so unfashionable to have money”) but is also fairly open about her own economic desires and needs.

When I ask how her summer is progressing, she replies that she works all the time, presenting her shows, hour-long conversations with interlocutors like Spike Lee and Frank Rich, and which involve substantial audience question and answer, which she has described as her favourite thing to do.

“So there’s an east coast aspect, places like Cape Cod, where city people go for the summer. I don’t like to do that because the theatres are very small, which means it’s the richest audience and the lowest fees. I already live in a country like that; I don’t need more. Last summer, I did the western version of that, which is all the ski towns in Colorado, but in the summer, unbeknownst to me, people go to these places to go hiking – hiking is the human activity I find the most puzzling.”

When she moved to the West Village as a young woman from New Jersey, Lebowitz paid $112 a month for a tiny room. Her friends in the then dingy and dangerous East Village asked why she didn’t live there instead, where she would have four rooms for the price of her single one.

“I’d say to them: ‘Yeah, but I would then get raped.’ That was important to me! And also because it [the West Village] was so gay – there was no comparison.”

I ask if she is aware of the recent New York magazine article about West Village girls. The piece profiles a particular subset of wealthy, overexercised white young women who live in the once avant garde neighbourhood; they are ardent consumers who love nothing more than a few $20 cocktails or discovering the hot new brunch spot, and seem indicative of the rampant neutering of Manhattan., of its descent into a kind of tournament for the very wealthy – a place once defined by artistic innovation which that has now become a backdrop for the elite to tick off their lists of aspirational experiences and restaurants. She nods, lightly grimacing. “Somebody said to me lately: ‘So you lived in the West Village – you were there because it was bohemian, right?’ I said: “No. I lived there because it was cheap. It was bohemian because we lived there.”

She pauses. “The person who asked me that [was a journalist] – you may not know this, but Scandinavia, though small, has about 100 million gay magazines. I know this because I’ve been interviewed by every single one. I was on the phone with one of these kids and he said: ‘When you first came to New York, you were my age – 22.’ Young people always tell me how old they are. Always during speaking dates, kids in the audience go, ‘I’m 26,’ then ask the question. They want to be congratulated. No one ever goes: ‘I’m 42.’”

Human beings are not good enough for socialism. We’re a horrible species so it always results in something horrible

Human beings are not good enough for socialism. We’re a horrible species so it always results in something horrible

We talk a little about an unfathomably popular biscuit bakery named Crumbl, which has a branch near her apartment, where she sees lines stretching round the block and marvels that anyone can be bothered to stand in line for anything in New York, where there are infinite options, and how TikTok has reinforced this sort of collectible-focused attitude towards neighbourhoods; this particular doughnut becoming the winning token of this street, that cacio e pepe the prize of the next one over – like Pokémon Go for people with too much money.

Lebowitz, however, doesn’t even have a phone. Does that ever present a problem? “Never. On these long rides I take for work, because I don’t have a phone, there’s always someone saying: ‘What the fuck do you do for nine hours? Do you listen to music?’ No? ‘Do you read?’ No. ‘What do you do?’ I think. ‘Is that boring?’ Not for me. I don’t find my thinking boring. Other people, I’m definitely bored by.”

It occurs to me then to ask if she keeps a diary. She doesn’t (“Guess what? I don’t need to live my life twice – once was enough”). I wonder if, despite being a luddite in practical terms, she might share the same existential oddness of a social media influencer. The tools of their trades could hardly be more divergent, but Lebowitz, like the influencer, is professionally herself. She shows no signs of interest in continuing her writing career; her job now is to exist in the form that has pleased the public, and to lend us her verdicts and inclinations and tastes, her signature style rendering them all the more marketable. This is not a criticism as such, but the idea of living so publicly, of your identity also being your meal ticket, strikes me as potentially draining. She lives alone; does she ever get lonely, want for company?

“I’m a split person. Half of me is very sociable. I do like parties, I like to go out, I like to go to dinner, I have my friends – and then part of me is really selfish. I have more than enough company. I’ve lived alone my whole life. The idea of living with someone else, I find so horrible. I would do anything in order to afford to live by myself, because the idea of a life spent yelling: ‘Don’t move this! Why did you put it there?’ is not tolerable.”

Lebowitz is describing here my exact social makeup, the relentless sociability alongside the requisite extended solitude to make up for it. It is cheering to hear about a woman in her later life who lives this way – to my mind the most ideal way – and having stuck it out in New York this long when it defeats or depletes so many. The reward for such persistence, for the New Yorker, is to complain, an activity she has elevated to an art form.

Is there a kind of person you think shouldn’t live in New York, I ask her, hoping she will not appraise me and say she’s looking at one. She is quiet for a moment and responds earnestly. “One of the large differences between people is this: people who like cities and people who don’t. And it doesn’t matter where. Someone who lives in New York has many more things in common with someone who lives in London than with someone who lives in Kansas, or even a rural part of New York state. So the problem is here; it’s my belief that people in the cities should make the laws.

“All this anti-immigrant stuff we have around now – this does not come from people who live around a lot of immigrants. The point of the US is immigrants. There is no other point to it. There is real fear here now, real hatred, ICE [immigration and customs enforcement] going into churches.” She shakes her head, momentarily, uncharacteristically at a loss. Then she takes off her sunglasses and says: “Someone said to me: ‘You have to stop speaking so badly about Trump – you’re going to get deported.’” I said: ‘Really? Where? To New Jersey?’”

Fran Lebowitz is on tour in Bristol, Manchester and London on 16-19 September. See here for more details

Photography by Getty Images