Photographs Jacob Lillis and Fashion editor Helen Seamons

London, late summer, is a place of return for Brett Goldstein. He is back among the terraced streets of Fulham, a south London neighbourhood 10 miles from the school he went to, and home to the house that he has been rebuilding for the past few months. The decision to leave Los Angeles, the new gravitational centre of his acting career, was not so much a rejection as a correction. California had given the comedian fame and roles he had once only imagined, but after five years bubbling in the froth of success he began to crave the firm and familiar: family close by, friends within reach, a city that did not especially care if you were on television.

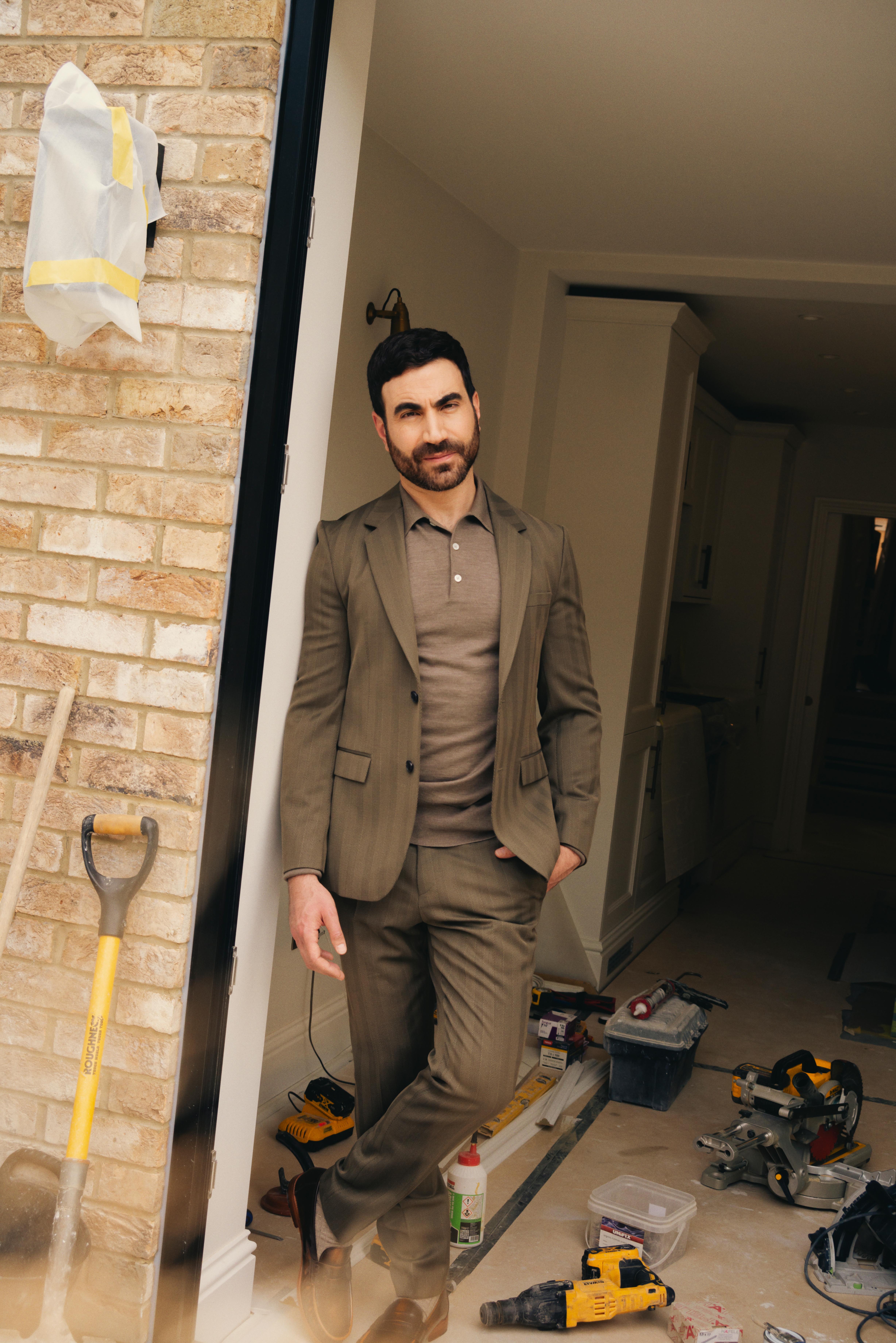

The house is handsome but modest, the sort of property that, 40 years ago, might have sheltered an overworked GP and his family, but which in London’s oligarch-ruined market presumably now commands a price tag achievable only by two-time Emmy winners. It does not yet look the part. The façade is shrouded in MDF boards that resemble a confessional booth for handymen, erected either to keep the dust in or the paparazzi out. Inside, the kitchen is a shanty town of Dewalt drills, Polyfilla guns and tubs of screws, arranged like still life for a macho Dutch painter.

There are no soft furnishings, no comforts of domesticity; just the odd patch of sage paint, tastefully peeking from dust sheets that cover the modesty of the kitchen island. Upstairs, in a bare bedroom, Goldstein perches uncomfortably on the tread of a shortladder. Every few minutes, a Heathrow-bound jumbo rumbles low overhead, causing a transatlantic tremor that shakes the handleless door ajar, which Goldstein dutifully closes.

He shoots, he scores: as Roy Kent in Ted Lasso. Picture by Landmark Media

It is late August and the sky is already struggling to contain autumn. Goldstein has been in town for the summer, living in a nearby Airbnb while he waits for the house to be finished. (“Two weeks to go,” he says, without conviction.) The decision to buy here was, like many in his career, equal parts pragmatic and instinctive. He had been shuttling between London and Los Angeles for three years, six months at a time, and thought it was time to plant something permanent. “I don’t know what home means any more,” he tells me. “I suppose it’s people, in the end, innit? I don’t want to seem cheesy. But seeing my friends here – that feels like home.” He pauses, hedging: “I have friends in LA, too, you know.”

Goldstein is 44, a writer, producer and, bewilderingly, still a jobbing standup. His public image, however, remains frozen as Roy Kent, the mercurial, foul-mouthed footballer of Ted Lasso. The series, which debuted in 2020, follows an affably optimistic American football coach, played by Jason Sudeikis, hired to manage a struggling English “soccer” team despite knowing nothing about the sport.

Goldstein was initially brought on as a writer. He was days away from starting a solo run at the Edinburgh Fringe and, not wanting to let the venue down, almost rejected the offer until his friend and fellow standup, Nish Kumar, said: “Fucking go, man!”

When he landed in the writer’s room on the Warner Bros lot, Goldstein settled into the role of cultural failsafe, steering the otherwise all-American team true in their depiction of English football culture. At one point he played his colleagues the music video for Vindaloo by Fat Les, explaining, “You think it’s Three Lions, but it’s actually this. This is the real culture.” Then, halfway through scripting the first season, he felt a tug he couldn’t ignore: the sense that Roy was a character he was not only meant to write, but one he was meant to play.

Related articles:

Shades of grey: jumper by Connolly; trousers by Oliver Spencer; and shoes by Russell & Bromley

Too embarrassed to say so aloud – “That would be a mad thing to say,” he recalls – he waited until the scripts were finished and then taped himself reading Kent’s lines at his agent’s office, with a Norwegian assistant drafted in to read opposite him. He sent the footage to Bill Lawrence, the show’s co-creator, with the caveat that they would “never speak of this again”. Lawrence’s reply – “This is fucking awesome” – changed Goldstein’s life. Roy Kent became the irascible heart of the series, a man whose Vesuvian temper disguised a vein of tenderness. Goldstein’s sweary but warm performance won him the Emmys.

The timing was uncanny. When Ted Lasso premiered, in the cloistered spring of the Covid lockdown, its unfashionable optimism arrived as a cultural balm. The remit, set by Sudeikis and Lawrence, was deceptively difficult: no snark, and always try to make things better. “We were living in a time where discourse was fucking horrible,” Goldstein says. Instead of cynicism, bluster and Trump-style strongman posturing, the team wondered: what if the protagonist embodied old-American values of leadership – curiosity, kindness, a willingness to admit he didn’t know what he was doing, but also a desire to help? “That,” Goldstein says, “was the DNA of the show.”

Goldstein’s own story was, in many ways, the obverse of Lasso’s. In his case, it was the Brit who had been parachuted into a foreign world, learning the codes of American television even as he tried to explain the lyrics of Vindaloo. Both Goldstein and Lasso were, in their way, experiments in cross-cultural translation, and both discovered that optimism, however unlikely the vessel, could be its own form of authority.

‘With standup it’s just me saying: Here’s what I thought today. You don’t need five trucks of equipment to turn up with you’: performing at The Ice House Comedy Club on February 17, 2023 in Pasadena, California. Photo by Michael S Schwartz/Getty Images

At first, the cast wondered if anyone would even see it. Apple TV+ was a new, unproven platform, after all. But then came word of mouth. “You can’t engineer it,” Goldstein says. “It happened because of magic.” By the second season, when the production trucks pulled into Richmond, fans were already waiting outside to watch. “That’s when I knew things had changed,” he says.

The change felt especially stark to someone whose earliest stage had been his parents’ living room in Sutton, where he performed skits with his sister as soon as he could walk and talk. “We weren’t doing Hamlet,” he says. “More like Cinderella.” After the siblings discovered Pete’s Dragon at the local video shop – “We rented it every week, probably spent a hundred quid on it” – Goldstein became obsessed with movies. He still hosts the podcast Films To Be Buried With, now nearing its 400th episode. As a child he dreamed of becoming a stunt man, or a director, or Indiana Jones. “Then, when I was about six at school, I wrote a short story about a shipwreck. My dad read it, and he was like: ‘This is really good… Do you know that ‘writer’ is a job you can do?’”

That throwaway encouragement made a lasting impression: “You look at all these things that happen when you’re a child – all the negative stuff – but there’s small things like that that really had an impact. I thought: ‘OK, well, I’ll keep doing this, then.’ And I was never, ever, going to do anything else.”

Still, Goldstein spent years working in the margins: bit parts, script-editing, plays and shorts – always making, always writing, always waiting for something to break. In his late 30s, it seemed his moment had arrived. He was cast as an Elon Musk-style figure in the pilot of a sitcom he describes as Scrubs set in a rocket factory. The show never aired and the setback prompted him to reassess his definition of success. “I got to a stage where I thought, I’ve missed my window. But that was OK, because I was working all the time, doing the things I loved.” He abandoned the cliché of success in exchange for something truer, if less glamorous. A week later, the Lasso call came in.

Work in progress: blazer and trousers both by Boss, polo by Connolly and loafers by Grenson

In Hollywood, he felt dizzy, invigorated, and lost. To steady himself, he turned back to standup in the evenings. He had begun comparatively late, at 27, after years of thinking of comedy as a magical, unattainable craft. He had long been taking plays to Edinburgh, but one summer realised he wasn’t enjoying the company of actors. “They didn’t feel like my people,” he says. “I found myself hanging out with the comedians instead, and I thought: ‘Oh, I feel so much more at home here.’”

On the Royal Mile he struck up a friendship with Kevin Shepherd, who was flyering for his own show. Shepherd told him there was no mystery to comedy, only graft. The simple advice made the impossible seem achievable. Goldstein tried five minutes in a pub room, a routine, or performance, jokes might still be the best of his career. The set looped in his head for a week, like a car crash, “But in a good way. It was just five minutes,” he says, “but I was like: ‘Oh, this is it. This is the thing.’”

He was hooked, even though, he admits, he “died every night” for the next two years. Still, he kept going, driven less by ambition than by compulsion. Gradually, he began to thread in material from his life. After graduating from the University of Warwick with a degree in film and feminism, Goldstein had gone to Spain, where his divorced father owned and ran a strip club in the tourist hotspot of Marbella. The experience became a rich seam for his solo shows: an unlikely backdrop for an instinctively private man to share, or expunge, taboo stories. “Standup is like heroin,” he says. “It doesn’t make me feel good, but it does make me feel normal.”

In LA, while living out of a succession of Airbnbs, he found security in the camaraderie of comedians, the ritual of hanging out at the back of gigs – especially at Largo, where the impresario Mark Flanagan “took me in like Fagin” and gave him regular stage time. Standup remains his anchor even now. (Earlier this month, he performed at the Union Chapel in Highbury, on a bill that included Lucy Beaumont.) “TV and film are amazing, but they involve 200 people and constant compromise,” he says. “With standup it’s just me saying: ‘Here’s what I thought today.’ You don’t need five trucks of equipment to turn up with you.”

A lot of what happens in my life goes into the work

A lot of what happens in my life goes into the work

Even as he defined himself against actors, Goldstein’s looks and bearing marked him out for the roles he felt least suited to. He has the face and physique of, if not a leading man, then at least his close understudy. In British comedy, good looks are, broadly, a professional liability. We prefer our comics – even the ones on Radio 4 – to have faces that are interesting rather than appealing. The instinct feels innate, vaguely regal: who wants to hire a handsome jester? Early in his standup career, Goldstein grew accustomed to waving away hen-do whoops as he strode onstage, eager to level the field enough for his jokes to land clean. And like many British people, he learned to mask ambition with self-effacement, believing the only fight worth winning is the one fought from the underdog position.

In Hollywood, the same approach is fatal. At his first agency meetings, Goldstein tried to charm the kingmakers by downplaying his achievements. “They called my agent afterward and said, ‘Why did you bring us this guy? He hasn’t done anything,’” he recalls. “In Hollywood you can’t just say: ‘I’ve been in some skits with my sister. Could you fund my film? By the way: It might be shit.’”

Soon, however, he learned to lean into what seemed to be his physical – if not his spiritual – destiny. His new film, All of You, casts him squarely as the romantic lead, a character whose dilemmas of longing and heartbreak will only fortify his standing as an object of desire. The project, co-written with William Bridges, began life as a short called For Life, set some 15 years into the future.

In that imagined world, technologists have invented a kind of weapons-grade Tinder: a scientific test able to unequivocally identify one’s soulmate, not only the best possible romantic partner but the person with whom you share something more elemental and ostensibly lasting: destiny.

At first, Goldstein and Bridges explored what such an invention might mean for the powerful – for the prime minister, say. Then Goldstein suggested they narrow the lens. Taking inspiration from War of the Worlds, they began to write a more intimate story about how a society-changing event might register in the lives of two ordinary people.

They filmed a short in which two friends walk to the clinic. Despite his scepticism, the man pays for the woman to take the test. Perhaps, we suspect, he hopes it will reveal him as her perfect match: a Jane Austen-esque set-up, hurled into the future.

Nearly a decade later, that fragment has expanded into a feature in which Goldstein plays Simon, a man in love with his best friend, Laura, played by Imogen Poots. When she takes the test, the result fractures their relationship. What follows is a series of vignettes in which their paths diverge and reunite, shadowed always by a love forbidden twice over: once by the old rules of fidelity, and again by the new rules of algorithmic obligation.

“It’s everything I love to write,” Goldstein says. “Two people, long conversations, passage of time. The mystery of what you don’t see. I love films where you must fill in the gaps.” The test, he insists, is less science than metaphor. “The belief that there’s one person for you, that things are destined – we’ve all had that, or still have it. Making it concrete lets you ask: what about the other loves? What do they mean?”

The film is funny in places, but predominantly melancholic, a study of longing, regret, and the mourning of lost futures. “Someone asked me recently if I dislike happy endings, because everything I write is sad,” Goldstein says. “Maybe it’s true. But dramas without humour are bad art. I watch them and think: ‘You’ve not observed life properly.’ People make jokes in war zones, you know? Life is funny and tragic and embarrassing all at once. So I like my dramas funny, and my comedies sad.”

All of You’s story is gently didactic, too. It cautions against placing one’s future in the hands of the supposedly omniscient gods of Silicon Valley and their sacred algorithms. Relationships, the film suggests, are as much about choice as destiny. There are no shortcuts: no machine can replace the unglamorous work of understanding yourself, recognising the patterns you repeat, or tracing the events that first described their circumference.

The irony of his career is that, just as he has stepped into the role of a romantic lead, he has grown more wary of the culture of exposure. He has retreated from social media, turning his phone screen black-and-white, deleting Instagram from the device altogether. The same man who once trudged home after bombing to 10 indifferent drinkers in a pub basement now found crowds waiting in Richmond to cheer his name. The vertigo between those two realities has never quite gone away.

His private life is guarded and yet leaks occur. Earlier this year, tabloids suggested he was romantically linked with Jennifer Lopez, his co-star in another forthcoming film, Office Romance. “He is one hot ticket and a real class act with talent to back it up,” said a “source”, in that uncanny, robotic syntax apparently unique to unnamed Daily Mail sources. “He is like the younger, better, British version of Ben [Affleck, from whom Lopez divorced earlier this year]. She thinks he is very cute.”

“I really hate it,” Goldstein says of this kind of attention, peculiar to a certain strain of British tabloid journalism. “I’m the luckiest man in the world – I get to do exactly the job I wanted, at the level I wanted. But I need a part of my life to be kept sacred, or it gets corrupted. Otherwise you can’t make art. I don’t want to engage in gossip. I want to create.” The privacy is not coyness but method. “A lot of what happens in my life goes into the work. I can look at a script and know exactly what I was going through when I wrote it. But that’s where I share it – in the art.”

The paradoxes are unmissable. Here is a man who distrusts algorithms, recoils from gossip, insists on privacy, and yet whose latest work is a film about technology that promises to quantify love, about intimacy made public and mechanical. In stepping into the role of a leading man, Goldstein has become something unlike the comedians he most closely identifies with, something the British standup world typically mistrusts: an object of culture rather than its satirist.

Conspicuous success, for all its undimmable allure, inevitably isolates. It is no surprise he has returned to London, not for career reasons but for community. And so the tension endures: the self-effacing British comic who feels out of place among actors, and the confident Hollywood player who must summon conviction to keep his projects funded and moving.

Someone asked me recently if I dislike happy endings, because everything I write is sad

Someone asked me recently if I dislike happy endings, because everything I write is sad

Goldstein’s resistance to certainty, to being defined or flattened into a headline, feels of a piece with the story he has chosen to tell. If All of You warns against surrendering to the neatness of algorithms, its co-writer and star seems equally determined to preserve the untidiness of his own life, even as the spotlight beads.

Back in the half-finished Fulham house, Goldstein seems both restless and oddly at peace. He is in London to film the fourth season of Ted Lasso, then hopes to return to Los Angeles to continue Shrinking, the Apple series he co-created with Lawrence and Jason Segel. He will keep flying back and forth, renting accommodation by the week, performing standup in small rooms, writing scripts in larger ones.

The house, with its boarded façade and bare rooms, provides an obvious but potent metaphor for this stage of Goldstein’s life: under construction, its shape visible but unfinished, the old patterned with the new. He is refitting his life as he refits the house: messily, noisily, while the jets keep time with window-rattling reminders that his commute now spans continents, not postcodes. For now he resides in the in-between, flitting between the back of a comedy club and the front of a film poster.

Still, he seems comfortable in contradiction. Permanence, he suggests, may be overrated; a fixed address, a settled definition, might even be a trap. “Maybe I’ll never have a fixed abode,” he says. “And maybe that’s OK.” The uncertainty that once felt like failure has become, in middle age, the apparent condition of his success: the freedom to keep moving, to keep remaking himself, to live with the hope of new rooms always ahead.

All of You is released on Apple TV+ on 26 September

Credits for opening photograph: blazer, top and trousers all by Brioni; shoes by Russell & Bromley

Grooming by Carlos Ferraz at Carol Hayes Management using Depuffing Wand for Therabody Beauty for skin and K18 for hair. Photographer’s assistant Mia Dawson.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy