“This is my Eggs of Evil,” says the Dutch artist Madelon Vriesendorp, pointing at a row of busts made out of eggshells and painted to look like Putin, Stalin, Hitler and Kim Jong-un, each in his own bell jar. Around us, in every room of her north-west London flat, is an ever-accumulating menagerie of objects and images made and collected by her: Candomblé deities from Brazil, Day of the Dead figurines from Mexico, plastic milk bottles exquisitely crafted by her into waterfowl, a bowl of eyeballs, American postcards of giant rabbits – an alternative natural history in which animal, vegetable and mineral swap souls, species intermarry, and the living and lifeless change places.

Madelon Vriesendorp's 'menagerie of objects

Vriesendorp has been awarded the Soane medal by Sir John Soane’s Museum in London, and will be giving this year’s Soane medal lecture on 18 November. There’s something appropriate about this recognition: Vriesendorp’s home has a lot in common with the famous house and museum Soane built for himself two centuries ago in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, if with added notes of Hieronymus Bosch, Looney Tunes and Sigmund Freud. “I love the way that everything is completely crammed,” she says of Soane’s array of antiquities and curiosities, “it’s like an audience; everything is talking to you at the same time.” Both she and he, she notes, collected sculptures of feet.

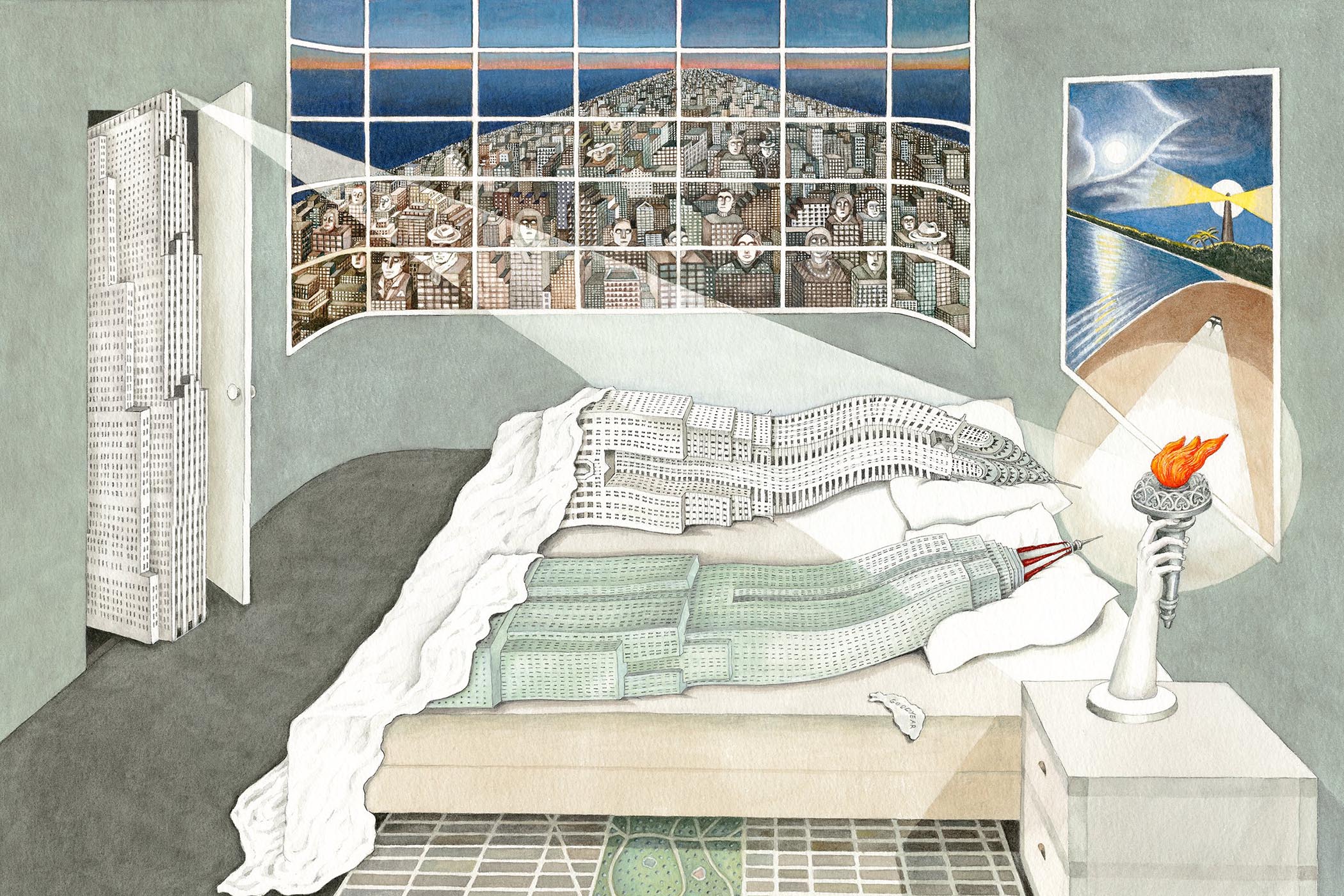

The Soane medal recognises people who have made telling but under-recognised contributions to architecture, who may or may not be architects themselves. Vriesendorp is an artist who half-accidentally created some of the most indelible and influential images of modern buildings. Her Flagrant Délit of 1975 shows the Empire State and Chrysler buildings lying in post-coital languor, while ranks of other skyscrapers gaze disapprovingly through an art deco window. She made this work and several others of New York and its fabric while she was living in the US with her then husband, the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas.

Her Flagrant Délit of 1975 shows the Empire State and Chrysler buildings lying in post-coital languor

These images bring to and bring out of architecture such things as desire, darkness, humour, playfulness, conflict, dream and absurdity – subjects that professional designers of buildings, constrained by the protocols and respectabilities of their business, often find hard to acknowledge. Vriesendorp’s pictures tell stories. They get objects to speak.

Koolhaas put Flagrant Délit on the cover of his 1978 book Delirious New York, with several more of his wife’s images inside. It was a last-minute decision, made after someone else used the picture without her permission in another publication in Italy, which showed that it had some reach. Delirious New York, which celebrated Manhattan’s “culture of congestion” and its ability to “arrange new and exhilarating human activities in unprecedented combinations”, acquired mythic status. It launched Koolhaas and the Office for Metropolitan Architecture – the practice he, Vriesendorp and two others founded – on a path to global stardom. Vriesendorp’s husband was for some time, probably accurately, described as the most famous architect in the world.

‘Behind every successful man is a surprised woman,’ she has said, and ‘behind every successful woman is an angry man’

‘Behind every successful man is a surprised woman,’ she has said, and ‘behind every successful woman is an angry man’

Mostly, though, Vriesendorp stayed out of the limelight. She continued developing her work and collaborated with Charles Jencks, the theorist and critic who promoted the idea of postmodern architecture, by creating images for his books. Jencks could be portentous and literal as well as brilliant. “I was drawing ridiculous cartoons all the time while he was talking. And then he laughed about my cartoons and I laughed about his crazy theories.” She created a “cosmic jacket” for him, decorated with stars, planets, pyramids and skycrapers, for a “cosmic party” at the “cosmic house” he made for himself from 1978, with its interior full of galactic iconography. “I mean, they’re not my ideas. I don’t mind. I just do drawings,” Vriesendorp says.

Her mother was Harriët Freezer, a “tough feminist writer” after whom, Vriesendorp is pleased to say, at least 16 streets and public places are named in their native Holland. (Vriesendorp’s daughter Charlie Koolhaas has set about photographing each one.) So Vriesendorp doesn’t need reminding of the politics of attention-seeking men who are helped by more reticent women. “Behind every successful man is a surprised woman,” she has said, and “behind every successful woman is an angry man”.

Vriesendorp is not especially comfortable talking about herself, diverting to anecdotes about others. “I’m always trying to sort of not be visible,” she says. “So many women, they don’t like to be visible, because the frontmen always get all the flak and all the hate. So in a way, you’re happy that you’re not on the frontline of criticism.” She is, though, fierce in defence of her name when others try to pass off her work as theirs.

Madelon Vriesendorp’s The City of the Captive Globe 1972

Her childhood, in a house “on the edge of a forest” between Amsterdam and Utrecht, also helped her develop her sense of mischief and subversion. Her father came from a “patrician” family in which Vriesendorp, her two sisters, brother and later her stepbrother “were always the black sheep”. Her parents divorced: in the 1950s, “you didn’t do that in those families”. “My aunt,” she recalls, “said to her kids: ‘Don’t look at them, they’re beasts’. So then, of course, that was an open gate for us to be completely beastly.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

She went to an “old-fashioned” art school but was expelled, when she and her fellow students responded to an exercise in drawing potatoes by peeling them, cutting them into “beautiful blocks”, then shredding them. He mother persuaded the school to readmit her. “I said no, I’m going with my boyfriend to London, I’m not coming back here. That was Rem.” The two stayed together, with some ups and downs, until they divorced in 2012.

So now, aged 80, she does her art – “I feel I have to make something every day” – and her collecting, in which beasts and sometimes beastliness figure prominently. Her home is like an artwork in itself. “I have nothing really designed in my house,” she says, meaning there is little by the way of the design classics with which many architects like to furnish their interiors, and instead the art brut of unknown toymakers, printers and figurine manufacturers. There’s a fascination with the sinister and the uncanny – “disturbing,” she texts me later, “is my way of operating” – yet the overall effect is celebratory more than dark.

Much life is there, as well as quite a lot of death, illuminated by wit. The atmosphere is also childlike, both in its spookiness and its wonders. An artist, Vriesendorp has said, has to recover “that focus you had as a child, you have to be super curious about stories”. Without ever having done much to promote herself, she now has works in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, but mostly she seems concerned, as she always has been, with playing her games and telling her stories.

Madelon Vriesendorp gives the Soane medal lecture at the Royal Academy of Arts, London W1, on 18 November

Photographs courtesy of the artist/Tilly Buckroyd