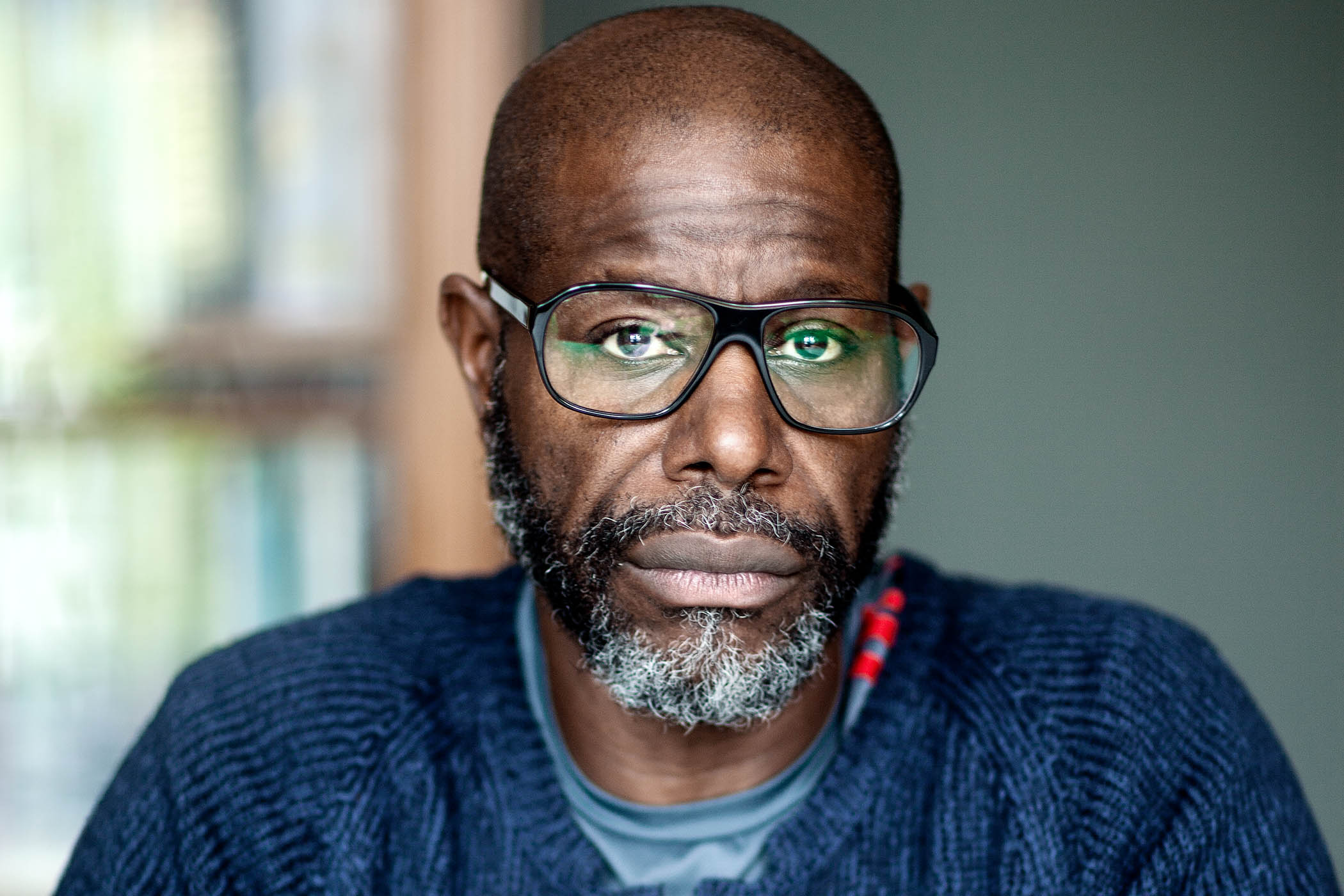

Portraits by Maarten Kools for The Observer.

Citizens of Amsterdam who walk, or more likely cycle, through the distinctive double arch of the Rijksmuseum this month will have the eerie impression that live surveillance footage is being screened above them. But before cyclists whizz under the imposing building and out the other side, a few will spot that something looks off. The trees are bare and spiky in several of the scenes, despite the fact that Amsterdam is still in full leaf, with autumn colour just edging in.

The images now being continuously shown on a huge screen on the museum’s facade are a cinematic account of Amsterdam’s wintery Covid lockdown of 2020. Shot over a three-year period by director and artist Steve McQueen, Occupied City documents a time when cycling from one place to another was one of the few sanctioned things that Amsterdammers could do.

Speaking to me at the museum, McQueen describes his 34-hour-long work as “a mirror” of contemporary Amsterdam. It captures the city by observing more than 2,000 different private, public and commercial addresses. “The point is to admire the whole city, in all its randomness, and to show the mundaneness of life as well as what is spectacular,” he says. It is “an experience”, and not an entertainment, he adds, so viewers can watch as little or as much as they like. What matters is what they take away.

McQueen, a winner of the Turner prize and the director of the best picture Oscar winner 12 Years a Slave, is still adjusting to the fact that his silent footage of Amsterdam is now a feature of the same urban landscape he filmed. “I love the way it is up there in a place of fluidity, with the bicycles going below it. It is integrated with the city now,” he says. “There is even footage of cyclists going through the Rijksmuseum in it.”

Occupied City is projected on to the facade of the Rijksmuseum

Crucially, though, McQueen’s film has another layer: his contemporary footage covers dark shadows of the past. The route his camera took through Amsterdam – the city where his wife, the historian and film-maker Bianca Stigter, grew up, and where McQueen moved almost 30 years ago – is a record of the lost geography of the second world war, and the period of widespread starvation that followed. Here, where he has filmed cafes around a square, people were once rounded up; there, where we see schoolchildren now playing, stood interrogation rooms used by the SS. In the modern square where we watch the police move in on anti-vaccine protesters, the Dutch Nazi party once marched.

It was Stigter’s book, Atlas of an Occupied City, an exhaustive Dutch-language chronicle of the repressed history of the Nazi occupation, that first inspired McQueen. He has followed her map around Amsterdam’s corners, canals and parks in a testament to all the crimes that left a trace, and to many more that didn’t.

It will now play continuously, come rain or shine, for passing citizens and tourists into the new year as part of the museum’s commemoration of Amsterdam’s 750th anniversary. Meanwhile, inside the building, the film will be screened with a narrative voiceover explaining what happened at each site during the Nazi occupation. The 34-hour film is an expanded version of a four-hour feature that has already been released in cinemas.

“Both versions were embraced by me from the beginning – the shorter film and the 34-hour version,” McQueen says. “It was never either this, or that. The point of it was always to show everything that went on in every single bit of footage in the longer form: the Covid lockdowns, Black Lives Matter protests and the climate change protests. It’s a period where so much happened; like the whole of the 60s in just three years.”

When families watch the shorter film, or read Stigter’s atlas, and first find out that something terrible happened in their street or even inside their house, Stigter, who joined McQueen last week to launch Occupied City, says they often find it difficult – especially if a Dutch Nazi sympathiser once lived there.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

‘Covid lockdowns, Black Lives Matter protests and the climate change protests. It’s a period where so much happened; like the whole of the 60s in just three years.’

‘Covid lockdowns, Black Lives Matter protests and the climate change protests. It’s a period where so much happened; like the whole of the 60s in just three years.’

Stigter believes the full film’s length is a recognition of all that history often misses out. “It covers all the random things you didn’t think were important at first,” she says. That sense of “randomness” is central to the project.

“The past is much more complex than we like to think and yet we all try to simplify it, even when we are still dealing with it,” McQueen says. “My film is like an archaeological dig, but at the same time, it is all accidental. As an audience hears the wartime story of a particular place, they connect the text with images I show, but they are not necessarily connected at all. The film simply shows the past and the present together.”

Amsterdam already offers walking tours that track the phases of the occupation; the initial registration of Jewish citizens, followed by waves of transportation to extermination and work camps, alongside Roma people and members of other minority communities. By the end of the war, more than 60,000 of the city’s Jewish residents had died.

Tourists understandably now line up to pay their respects at Anne Frank’s attic on Prinsengracht and at other more formal memorials. Underfoot, there are also the Stolpersteine, or “stumbling stones” – commemorative plaques that mark the homes of exiled and murdered former residents.

‘The point is to admire the city in all its randomness; to show the mundaneness of life as well as what is spectacular’

‘The point is to admire the city in all its randomness; to show the mundaneness of life as well as what is spectacular’

But McQueen’s film, in contrast, is a spectral tour of the way the past has been hastily overlaid. “I kept feeling like I was living with ghosts; that there were two narratives going on the whole time, and wanting to do something with that,” he recalls. “And then, hearing my wife in the next room, tapping at the typewriter keys, working on her atlas … Well, I thought that could be the soundtrack of my feelings: the past as text in the present day.”

The couple are content for others to take up the same challenge in previously war-torn locations: Stigter suggests northern France or Prague. But when I ask McQueen if he might use the method to mark the sites of atrocities from the trade in enslaved people, his response is firm. “No, I’ve done my bit on that with 12 Years a Slave. When Bianca and I were in Washington to visit [Barack] Obama at the White House, we did find the hotel where Solomon Northup [the protagonist of 12 Years a Slave] was kidnapped. There was no sign up. Nothing. We did try to erect a plaque.”

McQueen with his wife, the historian and film-maker Bianca Stigter, whose book inspired the film

Occupied City differs significantly from the literary genre of “psychogeography” adopted by writers such as Iain Sinclair or by Edward Platt in Leadville, his acclaimed study of London’s degraded Western Avenue. McQueen’s art is closer to the cinematic tradition of “city symphonies”, but it is really a study of the lack of evidence of the past, not of concrete remnants. In fact the director, ever a contrarian, believes the wiping away of a tragedy can be positive: “Sometimes the present should completely erase the past. It happens in this film when some kids are shown having their spliffs, totally unaware of their surroundings. It’s important.”

At Cannes, where the film premiered in 2023, McQueen said: “It is the mundane which is monumental.” Explaining this, he tells me: “The blood spilt back then is the thing that has allowed people to have the freedom to be mundane now. What Europe has come through in the last 85 years is a testament to freedom and we have to keep thinking about what that means. So, as an artist, I have never felt more useful.”

It is also important to McQueen that joy and hope are represented in the footage. So there are stories of resistance. His lens fixes on the home of a Jewish man who had never flown a seaplane before, but who commandeered a German one and flew his family to safety in England. Striking contemporary scenes also show a partnership ceremony, children skating on a frozen canal and a dog leaping to the sound of his master’s saxophone. Most movingly, the 262-minute film closes with a barmitzvah celebration. “Human beings always celebrate, even in the worst of times, so it fits,” McQueen says. “There is always time to be joyous. Party like it’s 1999, like Prince said.”

In emphasising the unwieldy nature of the past at this time in Amsterdam, McQueen’s newly public artwork highlights our unresolved understanding of the barbarity of war. “It is too big for us … Even in this 34-hour version, there are more stories than we can tell. You don’t even get a handle on it. We can’t comprehend it.”

This appeals to McQueen, who has a record of making us return to historic offences that are in danger of becoming troubling cliches; the beaten enslaved persons, reviled Jewish people. Grenfell, his 2023 film about the west London fire, wordlessly pointed at a painful national disgrace, while his recent feature Blitz was prompted by domestic disasters that were hushed up to protect wartime morale. The academic Will Brooker, who studied art with McQueen at Goldsmiths, University of London, praised his unflinching gaze. “He won’t cut away and is committed to shooting difficult and sometimes unpleasant scenes, which ties in with my sense of him from 20 years ago,” he once said.

McQueen was ambitious when it came to the great scale and complexity of the film that is now confronting Amsterdam daily. When it comes to its lasting impact on the story of the city, he is more modest: “I don’t know if it will change people’s feelings about Amsterdam much, but it will leave an impression, at least.”

Other Photographs by Jordi Huisman