Portrait by Suki Dhanda

In her bedroom in north London, 93-year-old Nemone Lethbridge turns her face to the sun and wonders how long she is going to have to wait before her husband Jimmy’s murder conviction is quashed. She doesn’t have for ever. “I’m hanging on,” she says. The light captures her skin’s translucent frailty – but her eyes are bright with resolve. “I’ve spent my life as a lawyer fighting for justice, and this is my most important case. Clearing Jimmy’s name would mean everything to me. It would be a vindication of what I’ve spent my life working for.”

Lethbridge has had the kind of life that would lend itself to a film. A daughter of the Raj, born in pre-partition India, she had a stellar career at Oxford, was one of the first women to be called to the bar and defended the Kray twins in court while she was in her twenties.

Then, one night in 1958, she met a man in a London pub whose life would be entwined with hers for ever: Jimmy O’Connor, then aged 40. He was lucky to be alive at all: 16 years earlier, in 1942, he had stood in the dock while a judge in a black cap sentenced him to be hanged for the murder of George “Donk” Ambridge, who’d been found dead in his flat after a break-in.

O’Connor’s sentence was commuted and he was released on licence in 1952. Which is how he came to be in the Star Tavern in Belgravia one evening in 1958, sharing a drink with the beautiful young Lethbridge. He told her straight away he wanted to marry her; she said: “In your dreams.”

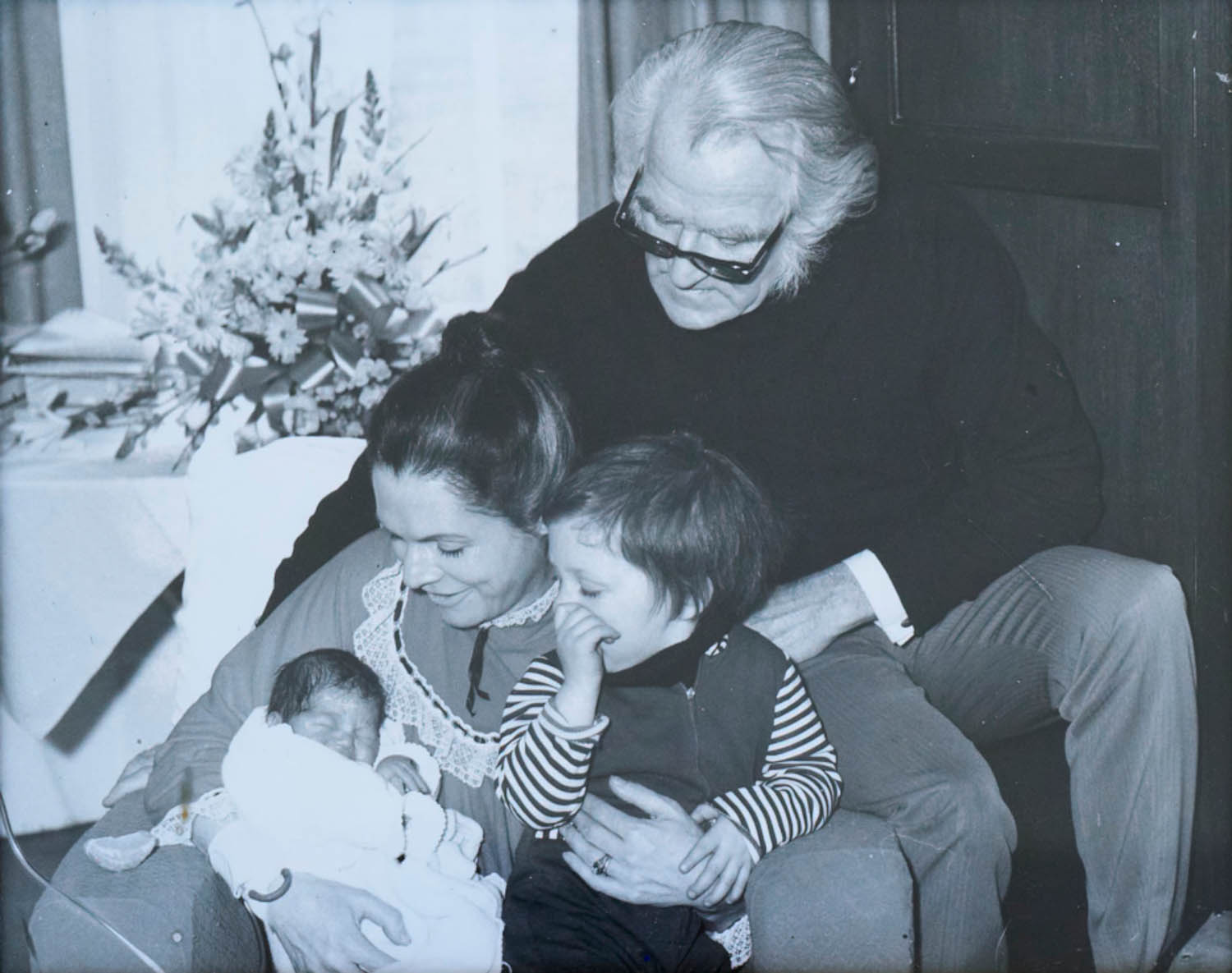

Nemone Lethbridge with her husband, Jimmy O’Connor, and their sons Ragnar and Milo in 1972

But before long they were a couple, and though there would be plenty more twists in their story before O’Connor’s death in 2001, her life’s purpose from then on would be overturning his conviction for murder.

“He didn’t do it,” Lethbridge tells me now, as she has told hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people over the last 70 years. “We spoke about it many times and his story was always the same: he wasn’t at the scene. He did not kill Donk Ambridge. Jimmy was certainly no angel – he was a small-time crook and he’d served time – but he wasn’t a murderer. He was stitched up by the police, who were desperate to pin the blame on someone. Jimmy turned out to be the best candidate.”

The fight to clear O’Connor’s name has come to a head several times over the decades since his conviction. There was an appeal in the early years, which he lost. Then documents were released showing prosecution evidence had been falsified against O’Connor at his trial. As long ago as 1967 the then home secretary agreed there were “troubling aspects” to the conviction.

Then, in 1995, the son of another man implicated in Ambridge’s murder said his father had done it. But each time that Lethbridge’s hopes were raised, they were to be dashed. Now comes perhaps the final roll of the dice: Lethbridge and O’Connor’s sons, Ragnar and Milo, have made a podcast for BBC Radio 4 that will be broadcast this week. They hope the new evidence they’ve uncovered, having dredged through box after box of paperwork in the basement of the family home, will at last prove their father’s innocence. Their findings will be unveiled in the series and are currently being examined by Mark Harries KC.

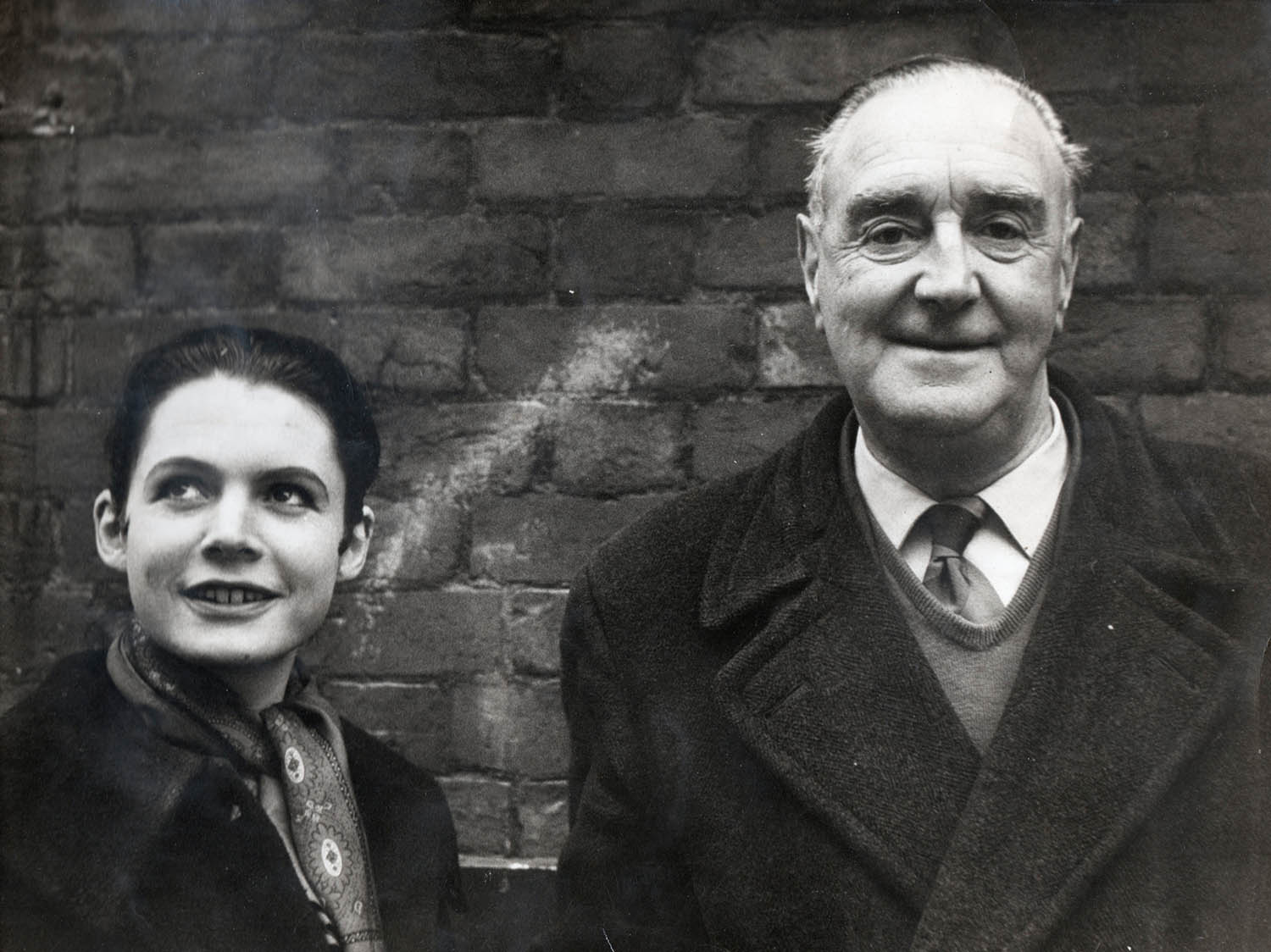

Lethbridge was one of the UK’s first women barristers

Lethbridge, these days confined to her bedroom after a series of falls, is feeling optimistic. “I feel more hopeful than I have for decades,” she says. If Harries agrees they have grounds for an appeal, he will take the case to the Criminal Cases Review Commission. “I’ve dealt with them a lot and I’ve found them hopeless,” says Lethbridge dryly. “[Labour peer] Charlie Falconer described them as lazy, useless and incompetent. But, happily, their chair has resigned, which gives us hope.”

Lethbridge and O’Connor had little in common when they met. She was 26; he was 40. She came from upper-middle-class military stock; he came from working-class Irish labourer folk and was raised in the part of London he always called “County Kilburn”. But they were both Catholics – him by birth, her by choice – and for both of them, the law was the bedrock of their lives. She because she had chosen to work in it; he because he had ended up on the wrong side of it, and was determined to prove his innocence.

By the time the couple met, O’Connor was using the Ruskin College correspondence course he took while at Dartmoor prison to work, first as a journalist, and later as a playwright. Lethbridge was at the bar, though her reception had been somewhere between lukewarm and frosty. “I only got a job at all because of good old-fashioned nepotism – a friend of my father’s,” she says. “The clerk of my first chambers told me I was an experiment he hoped wouldn’t be repeated. He said if I needed the bathroom, I’d have to go to a cafe up the street.”

In fact, it was her low status in her law firm that meant she was available to go to defend two brothers who were suspected of trying to steal a car – her first brush with the Krays, with whom she became a favourite for always getting them off their charges. Ronnie, who seemed especially smitten, once told her he wished he could take her to the moon; on another occasion, the twins offered her a large amount of cash for all she’d done for them (she turned them down). She remembers the Krays with affection, and is godmother to their brother Charlie’s daughter.

Lethbridge and O’Connor with Ragnar

Aware that Lethbridge’s career could be jeopardised if she was known to be the wife of a convicted murderer, she and O’Connor married in secret in Dublin. A couple of years later they were rumbled by a tabloid and the resulting story meant she was asked to leave her chambers, aware another firm would not take her on.

In search of solace, the pair went on holiday to Greece. It was 1961 when they found themselves on the then unspoiled island of Mykonos and decided to stay put and enjoy the sun, sea and glamour. One neighbour was the violinist Yehudi Menuhin, whom Lethbridge recalls standing on his head, and behind her on the shelf in her bedroom is a grainy black and white photograph of O’Connor sitting at a table with shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis. “We saw him a few times,” she tells me. What about Jackie Kennedy? “Yes, I met her once – she was getting off a boat.”

Their network even stretched to Donald Trump; another “great chum” of O’Connor’s was US lawyer Roy Cohn, who holidayed on Mykonos and whose young protege was the up-and-coming, blond-haired Manhattan property broker.

At this point, Lethbridge and O’Connor – spending their summers on the beach and their winters in London – seemed to have put the difficulties of her thwarted career and his criminal conviction behind them. They were making money; she had followed him into writing TV plays, and both had their big breaks through BBC series The Wednesday Play, which put real life front and centre. O’Connor’s 1965 drama 3 Clear Sundays, directed by Ken Loach, told the story of a young labourer who is sentenced to hang for a minor crime. Millions tuned in, and it was seen as instrumental in ending capital punishment, which was suspended the same year. Lethbridge, meanwhile, mined her own experiences to write, among others, Baby Blues, a 1973 drama in the BBC’s Play for Today series about the previously taboo subjects of miscarriage and postnatal depression. Life in Mykonos still had its tragedies, and she had suffered several pregnancy losses.

Our family has never been free of Jimmy’s conviction, and never will be until it is quashed

Our family has never been free of Jimmy’s conviction, and never will be until it is quashed

And then, on the eve of her forties, Lethbridge finally had a baby. Ragnar was born in 1970; Milo followed a couple of years later. By then, though, O’Connor was losing his currency as a TV writer. “The one-off play was out of fashion and Dad wasn’t a series writer,” Milo tells me. “Meanwhile, Mum still wasn’t able to practise law – and they were running out of money.”

Lethbridge was up against it with two young children, no job and a husband who was drinking too much. “It was all catching up with him,” says Milo. “He had no work, he was no longer the TV man of the moment, and he was still a convicted murderer out on licence. In Greece, he had felt free – but now they decided to return to London, and to separate.”

Lethbridge recalls “some wonderful years, and some very difficult years. Back in London, I had to raise the children in poverty and Jimmy couldn’t contribute to their upkeep. I never stopped loving Jimmy, but I couldn’t live with him. I had to think of the children.” She bought a house in Stoke Newington, where she still lives now with Milo, his wife and their four children. “We’ve lived here for more than 50 years,” she says. Milo adds: “Today, it’s a desirable neighbourhood, but when we came here, it was a rat-infested wreck and we were living on lentils.”

Divorce for Lethbridge and O’Connor was not like divorce for most couples. “They always referred to one another as their ‘husband’ and ‘wife’, and there was never anyone else – for either of them,” says Milo. “Dad came for Sunday lunch every weekend. He was never what you’d call a modern man: he didn’t help with the cooking or the washing-up. He used to drink a lot, but he was always a calm person. He seemed to me to be a safe presence. He was very hard to wind up, very streetwise. If someone got uppity, it never bothered him.”

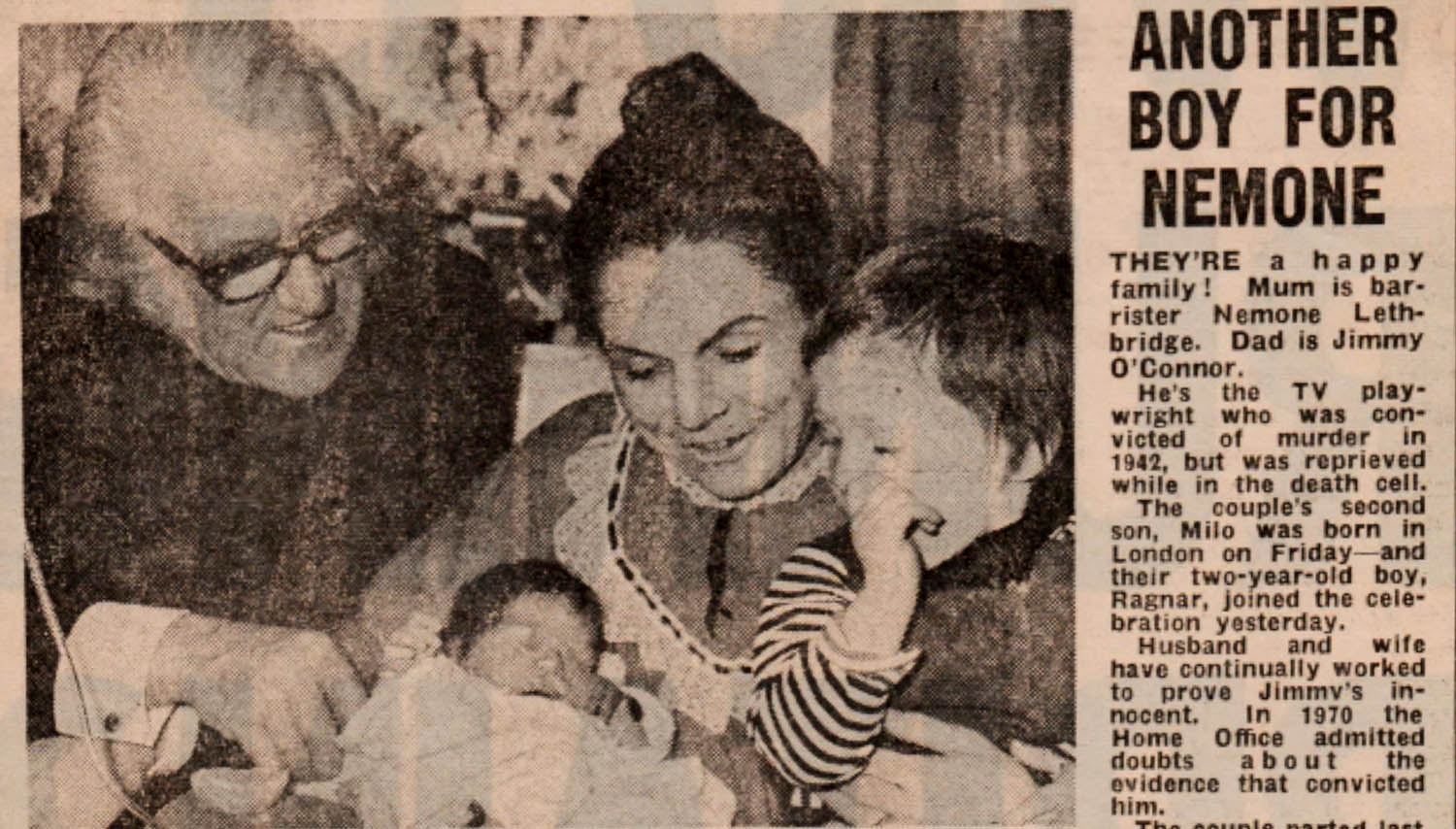

Milo’s birth makes the headlines

In 1981, the tide turned for Lethbridge when she was able to return to the bar. “It seemed like the end of a nightmare – it had been 20 years in which I couldn’t work in the profession I loved. It turned out a lot had changed while I’d been away. I was astonished: there were black faces, and women, in chambers. I couldn’t believe it – it was wonderful.” Lethbridge was able to work on legal aid cases representing those with significant challenges – work she continues to this day, reviewing cases and offering advice through the legal centre she set up 30 years ago at her parish church. “There are so few lawyers who represent asylum seekers, so that’s a lot of what we do. People are in real need and you can’t but want to help them.”

Like their parents, Ragnar and Milo too would have their moment of fame. Milo proudly shows me a copy of Just Seventeen magazine from 1993: on the cover is a picture of the five long-haired band members of FMB. Ragnar played guitar, Milo played bass. When the band folded, Ragnar went to work as a trader but Milo decided to study law. “Mum’s career had been massive, and I knew I’d never be as successful as her,” he says. “But Dad’s story, his wrongful conviction, motivated me to follow her into the law.”

It gave him an insight into what his mum had been up against. “I was having a drink one evening with a colleague after a case at Southwark crown court, and she said to me: ‘The problem for your mum was she made a bad marriage. Things would have been different for her otherwise.’ It made me realise how much this thing still matters – how our family had never been free of Jimmy’s conviction, and how they never would until we got it quashed.” That, he says, is why he and Ragnar decided to go back down into the cellar of their family home, to root though boxes that hadn’t been touched for years and revisit their dad’s story.

Lethbridge with a colleague while representing the Krays in 1957

O’Connor’s defence, from the original trial, was always his alibi: he said consistently that he wasn’t at Ambridge’s flat the night he was killed. There were some big surprises for his family in the paperwork they uncovered in the basement and elsewhere, especially one document that seems to undermine everything they thought they knew about O’Connor’s involvement in Ambridge’s murder. At the end of their investigation, though, Lethbridge and her sons still believe their case for an exoneration is strong.

Even in her nineties, it’s easy to see the still brightly burning spark in Lethbridge that drew O’Connor in all those years ago. She is straight-talking, fearless and wryly funny. As she sifts through the many layers of O’Connor’s case during our conversation, she is aware of every name and date. Nothing seems to stump her, even when Ragnar asks her on the podcast if her being a lawyer was part of why O’Connor wanted to be with her.

Ragnar says he knows there was love there but did part of the attraction lie in her sharp legal mind? Was there a hope on O’Connor’s part that being married to Lethbridge would help him overturn his conviction? “He thought he’d hit the jackpot,” she replies. And when exoneration didn’t come to pass – when O’Connor eventually died without his conviction being quashed – she says he was “deeply disappointed in me”.

It’s not hard to see why Lethbridge is so determined to hang on to see justice done. She was already a fierce opponent of capital punishment when she met O’Connor; perhaps for her too that was part of the attraction: the chance to fight to right a wrong so terrible it had put a young man in a condemned cell.

O’Connor’s sentence was commuted in 1942 just two days before his scheduled execution. Today, there is a similar sense of urgency for his widow. Hoping for the conviction to be overturned is, Lethbridge agrees, partly what’s kept her going all these years. How will she cope, after everything she’s been through, with more disappointment? She turns to the sun again and gazes out of the window; there’s a long pause. And then she snaps into life again, with a voice that’s strong and steady, saying: “I’m a tough old boot.”

All episodes of The History Podcast: The Magnificent O'Connors are on BBC Sounds from 1 October and released weekly on BBC Radio 4

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy