Portraits by Suki Dhanda

An intimate gig for Radio 2 in the BBC’s live theatre. Pulp – singer Jarvis Cocker, keyboard player Candida Doyle, drummer Nick Banks, guitarist Mark Webber – are dotted about a small stage. Surrounding them are several other musicians, including a four-piece string section; during Sorted for E’s & Wizz, they put on bucket hats.

It’s a scrum on stage, but Cocker still finds room to do his thing. He throws grapes like sweeties into the crowd: “Who wants a red? A green?” He discusses how several Pulp songs concern women whose names end in “a”: “Deborah, Sylvia… and now we’ve got a new song about Tina.” His chattiness brings the audience in, but Cocker is far from an everyman. The man has his own particular glamour: he throws poses like an animated anglepoise, sweeps his hands before his face like a serious mime artist. His long-limbed jumps make geometric shapes.

Afterwards, Pulp consider their performance.

“I liked that everyone was very near us,” says Cocker. “I could direct particular lines to people. Some people looked a bit frightened of that. And the new songs worked.”

Doyle: “I felt like people were behind us. Not thinking, ‘What the hell are they doing?’”

Webber adds: “…‘God, I thought we’d seen the last of them.’”

Ah, Pulp. Confident yet diffident, proper performers who don’t like to shout about themselves. Hardcore representatives of the Crimplene class, charity shop misfits who’d get “a smack in the mouth just for standing out”. Outsiders with their noses pressed up against the VIP glass.

Or are they? The Radio 2 concert is actually the smallest gig Pulp have played in some time. Since 2023, with their This Is What We Do for an Encore tour, Pulp have been appearing as big-name headliners, playing in front of tens of thousands as the closing act for stadium gigs and festivals. They’ve joined their Britpop contemporaries Blur and Oasis as a band not only for those who like to recall nostalgic glories but also one that attracts a new audience, excited young people who recognise themselves in Mis-Shapes or Freaks or Common People. Their June gigs at the O2 sold out in minutes; they’re playing enormo-halls across Europe and the US until the autumn. And, 24 years since their last LP, they’re bringing out a new album, More, with a single, Spike Island, that has done better in the US than any previous Pulp release (No 38 on the Adult Alternative Chart!). Against all the odds, Pulp are slap-bang in the middle of their second imperial phase.

It’s the day after the gig, and the band have just emerged from a group photo session. Though it is Cocker who we usually think of when we refer to Pulp – a uniquely British hero: wry, skinny, be-spectacled, be-corduroyed – this is a band. A Sheffield band, specifically. Formed after a 15-year-old Jarvis dreamed up the idea in school in 1978 – he came up with the name Arabicus Pulp, and drew pictures of what they’d wear – Pulp were a long, slow burn. Working their way through various lineups (24 different members in total; Mark, from Chesterfield, once head of their fan club, only joined in 1995), they finally broke through with His ’n’ Hers in 1994, and followed it up with the era-defining Different Class in 1995. The band are usually remembered as the six cutouts in the wedding group on the cover of Different Class. But violinist/guitarist Russell Senior left in 1997, unable to cope with what Pulp had become (he cited too much focus on Cocker and having to play fashion shows); and bassist Steve Mackey died after suffering three AVM brain bleeds in 2023. (During the Encore tour, Cocker regularly dedicated Something Changed to Steve, and More is, too.)

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Bands can be an impenetrable gang, a bolshy family, but Pulp are more like four quietish cousins. Not self-conscious, but not particularly close, and certainly not starry – even Cocker. Banks, chatty, slightly eccentric, is the easiest company. Doyle, tiny, with glamorous blond hair, is quietly friendly, as they all are. Webber is reserved, accurate, occasionally spiky. Cocker is Cocker: more watchful than you might expect, articulate and a little shy.

At the lunch table, chat doesn’t flow. “So,” says Cocker, “what’s everyone doing this weekend?” A pause, filled by Banks, who, it turns out, is going to a hen night.

Not a stag night?

“No,” says Banks, firmly. “A hen.”

It might seem strange that such modest people have become a stadium act, but actually, playing live has always been central to Pulp. Not in a cheesy way – Cocker has long stood against the “hold the microphone out to the audience for a sing-song” method of getting a gig going – but creating an interesting performance is part of their raison d’etre.

Cocker: “We’ve always slightly not wanted to be like a normal band. The first thing that we did after Russell joined [in 1983] was put on a play called The Fruits of Passion.”

Banks: “We used to spray footballs silver and make a giant mobile five minutes before going on stage. Maybe not the best idea.”

Cocker: “There was one pub in Sheffield where all the bands used to go, the Hallamshire, and they just talked about really boring things all the time. Amplifiers, stuff like that. We hated all that. And when we were asked to do these gigs, I was only interested if we could put on a show.”

So, for the Encore tour, the first sight of Cocker was in silhouette, in front of a big sun, at the top of a central staircase. The visuals were interesting and playful, and there were, as mentioned, a lot of other musicians. Fifteen in fact; many from his solo project, Jarv Is, five of whom form what Cocker calls Pulp 2.0. (As a side point, bands don’t usually bring on lots of extra musicians for big gigs, because they need to be paid, meaning there’s less money for core members.) They did 13 UK concerts, which were a success, so they added more. And then came the idea that they might write a new album. “We didn’t have a contract,” says Webber, “no one expected anything of us, so we felt free.”

This is very Pulp, meaning slightly haphazard. Most bands make a new LP before they tour, even if it’s an unexpected return (Blur did this). Some, like Oasis, refuse to make new music at all. Pulp fall somewhere in between, doing things the wrong way round. Cocker thinks doing a new record might have something to do with Mackey dying; also, his mum died at the beginning of 2024: “It does make you feel like, OK, you are still alive and you still have the opportunity to create.” Anyway, once the decision had been made, they worked on the songs and recorded the whole of More in super-quick time – just three weeks (“one song a day,” says Doyle, “pretty much”). And they could only do this because, unlike with previous albums, Cocker had already written the lyrics.

He always used to leave his words to the end, he says, because he really had to build up the courage to do them. “I’d get into a dangerous headspace where I’d think, ‘Oh, this is the only chance I’ve got to do this song.’ And it would become too much,” he says. As his words were so private, that would also put him off doing it. This time, he tried to be less self-conscious, sometimes just singing his phone notes without really analysing what they were. Though, as a lyric-writer supreme, he would then tweak away at them until they were right. And there are some excellent lines: “I exist to do this/ Shouting and pointing”; “So you move from Camden/ Out to Hackney/ And you stress about wrinkles/ Instead of acne”; “I know it’s all about the journey not the final destination/ But what if you get travel sick before you’ve even left the station?”; “We thought we were just joking, trying dreams on for size/ We never realised we’d be stuck with them for the rest of our lives.”

According to Cocker, he used one set of notes across three songs in the end: Spike Island, Farmers Market and Background Noise. Farmers Market is a fictionalised account of him meeting his wife, Kim; a little like the 1995 song Something Changed, in that it describes grabbing an opportunity to talk to someone who might change your life. Background Noise is interesting because it’s the flipside of that.

I love the sound of a fridge. Sometimes I just go down in the middle of the night to listen

I love the sound of a fridge. Sometimes I just go down in the middle of the night to listen

“Yes, it’s about how relationships, if you’ve been in them for a while, you can become blind to them,” says Cocker. “They become like the buzzing of a fridge. Something that you would only notice if it stopped.”

Something annoying but ignorable?

“No, I love the sound of a fridge,” he says. “Sometimes I just go down in the middle of night to listen... It’s more about how the secret to happiness in life is to find ways of carrying on appreciating things, rather than letting them become background noise. I’m not an expert on that, by the way. I’ve often almost spoiled things by taking them for granted.”

Doyle: “So it’s like being present, appreciating this person every day in this situation.”

Cocker: “Yes, that’s it. Living in the now.”

If that sounds a little un-Pulp, rest assured the album tackles several familiar themes: relationships, ageing, unrequited desires (Senior once described Disco 2000 as “about meeting a girl at school and then losing touch… standard Pulp fodder”; Tina is this type of song, though darker).

“I’ve only got very narrow interests,” says Cocker. “Someone said to me when they heard the album that it’s age appropriate, and you could think that was rude but actually, it’s just good to realise that being old is all right.”

On the back cover of This Is Hardcore, which includes the song Help the Aged, it says: “It’s OK to grow up … just as long as you don’t grow old.”

“I still would endorse that,” says Cocker. “It’s OK to develop and change – that’s growing up. Growing old, to me, is like forming a shell and thinking, ‘I’m not bothered with the world’. You’ve got to stay curious about what’s happening, because you change as well. And that’s the thing that’s hard to cope with if you’re like me.

“I’ve never liked change. I’ve always wanted things to stay exactly the same. I think that’s because you don’t feel that you change as a person, but you do. When you remember being a kid, you feel like it’s the same person, you feel like you are fundamentally the same.”

“When I was young,” says Banks, “I thought life was over at 21. I remember being around 10 and thinking that. I thought, ‘Well, at 25, I’ll probably be at home, pipe and slippers.’ It was logical really, because when you started going out in Sheffield, they had a nightclub called Top Rank, with an over-21s-only night, and everyone called that ‘Grab a Granny’… But here we are, in our mid-50s and beyond, still titting around in a band.”

If you ask Pulp about the 1990s, the decade that embedded them into public consciousness, the thing they remember most is Glastonbury 1995. Famously, the Stone Roses were set to headline the Pyramid stage on the Saturday night, but guitarist John Squire broke his collarbone with only a couple of weeks to go. Pulp stepped into the slot and their performance was triumphant and typically Pulp. They played a few songs no one had heard before (Sorted…, Disco 2000), which you shouldn’t do in a headline slot. Common People had only just been released, but somehow everyone knew the words and belted them out.

Banks: “God, the whole thing was terrifying. Terrifying, but exhilarating.”

Doyle: “I felt like I’d moved to a different planet when we came off stage. Completely out of my body. Afterwards, I went to bed, I was absolutely freaked out... You all went and watched the sunrise.”

Banks: “Not me. I was forced to listen to Robbie Williams doing his poetry backstage.”

Webber: “He was doing that all weekend. That wasn’t connected to our concert.”

Pulp camped backstage that year, not the usual star accommodation, and possibly why they couldn’t quite get away from Robbie Williams. (A bleached and spiky Williams was breaking out of the boy-band strictures of Take That: he chatted to everyone he saw and appeared on stage with Oasis.) Glastonbury 1995 did feel a little like something was shifting, the UK morphing to celebrate an alternative, outsider youth culture. At the time, Cocker wrote that he felt that it was significant, not because Pulp were headlining, but because he had a sense that everybody there – around 80,000 people – were of similar minds.

“Which was unusual,” he says now. “Because it was before mobile phones. So shared stuff would be rumours, rather than real, like ‘Oh, Cliff Richard has died’. And you couldn’t check. You were in your own world for those three days, but at that time it felt like so was everyone else.”

After Glastonbury 1995, for the next year or so, Pulp entered that first imperial stage, and were busy being Pulp for several years, up until We Love Life in 2001. After that, for more than two decades, they created their own lives (though they did play Glastonbury again in 2011). Cocker hosted a 6 Music show and several series for Radio 4, presented TV programmes on outsider art, forged a solo career, gave lectures. He’d often be seen at art shows and gigs: Jeremy Deller, Baxter Dury, Chilly Gonzales. Webber, a natural academic, became a curator and programmer of avant-garde films for places such as the BFI and the Tate.

Doyle trained as a therapist and was a counsellor for 13 years.

“I can’t do that any more,” she says cheerfully. “I can’t do it with Pulp in my head, and it does make you a little bit miserable… For a while, I thought I could go and work at those places where pop stars go and chill out.”

Banks: “What, rehab? ‘So you’ve come off tour and there’s no one to wipe your bottom. How do you feel?’”

Doyle: “Well, I thought I was going to go crazy in 96, when we were in the band, so I thought, ‘Oh, that’s good, I can speak from experience’. But then I thought, ‘I can’t face those people. They’d drive me nuts.’”

Banks, being a drummer, drums (he joined a Pulp tribute band recently for one night). He also keeps an eye on social media. “Do you answer people’s questions?” asks Cocker, astonished; Banks says he does, sometimes, but has also been building “a sex pond”.

Sorry, what?

Banks: “It’s down the bottom of my garden. We had this big bank of earth and we started digging into it. And I sometimes go on holiday with Richard Hawley [himself a former Pulp member], and we’ve stayed in places that have got a jacuzzi, so I said, ‘I’m digging this thing out. Maybe I’ll put a jacuzzi in.’ He said, ‘We don’t call it a jacuzzi. We call it a sex pond.’”

But now they’ve had to put other projects aside, even the sex pond, because Pulp are back, back, BACK – and people are excited. Is it fun?

“I’m enjoying it a lot,” says Doyle. “This is my favourite time ever to be in the band – but I don’t like to think about being in Pulp. If I think about it too much, it does my head in.”

“I don’t really understand it,” says Webber. “I can’t explain it.”

“There’s no manual,” says Banks. “I think that kids these days think there is.”

Cocker ponders.

“In recent years, there’s been a lot of mentoring of pop stars, like in X Factor. Which gives an idea that you can be taught how to do something, and there’s a right way to do it, a wrong way to do it. But a band is just people who have started off together. You learn your own way of doing it. Like we tried to do a song that sounded like Barry White – what a crazy thing to do, you know, for some people in South Yorkshire to try to sound like Barry White – but you end up inventing your own ways, and that’s good. It’s a self-sufficient thing, rather than this template that you have to adhere to.”

“We all have our own ways of playing our instrument,” says Banks. “Like Candida has got a wonderful, unique way of playing the keyboard which no one else has got, and that just brings, I think, a massive spin of differentness and how all of us interact.”

Pulp is the whole band, that unique combination of ideas and talent; and also a world that you enter into, that takes certain things seriously, and others not. A few years ago, Cocker wrote a book, Good Pop, Bad Pop, that used objects – personal ephemera such as matchboxes, notebooks and toys that he’d kept in an attic – as a way of telling his autobiography. Webber, too, brought out a book last year – I’m With Pulp, Are You? – that’s similarly filled with physical objects, real life detritus of being in Pulp. The band is a celebration of the ordinary, the amateur, the physical; a rejection of dull professional virtual slickness.

“I probably should just chuck all my stuff away,” says Cocker, who recently moved to Derbyshire and will be selling his London home in the next few months. “People don’t have so many physical objects any more, do they? Their life and memories are on their phone. But I worry about that. And the objects really bring back very, very vivid memories, so I don’t know whether I can get rid of them. I’ll have to be buried with all my objects. Like Tutankhamun. It’ll be an enormous coffin.”

It can be hard to get older when you’re weighed down by the past.

“It’s not weighing down though, is it? It’s not physical, because physical work doesn’t really exist any more,” says Cocker. “And that used to really wear people out, so then they really would be old, because they were physically worn out. Whereas, although we can say, ‘Oh, it was hard work playing yesterday,’ it wasn’t really that hard. I was in a taxi a few months ago and went past lots of young kids queuing up to go into somewhere like a roller disco. And they were, like, mid-teens, and you could sense all that unsureness, because they were wondering how you act when you’re on the threshold of being an adult. I would not want to go back to that. That’s one of the things about getting older that’s good, at least you don’t have to do that any more.

He pauses. “I used to think that one day I was going to wake up and think, ‘Oh, yes, I’m an adult now, I know how it all works. Let’s go have some sushi.’ That day never happened. But you do get to know yourself. For better or for worse.”

Pulp’s new album, More, is released on 6 June and they tour the UK and Ireland from 7 to 21 June

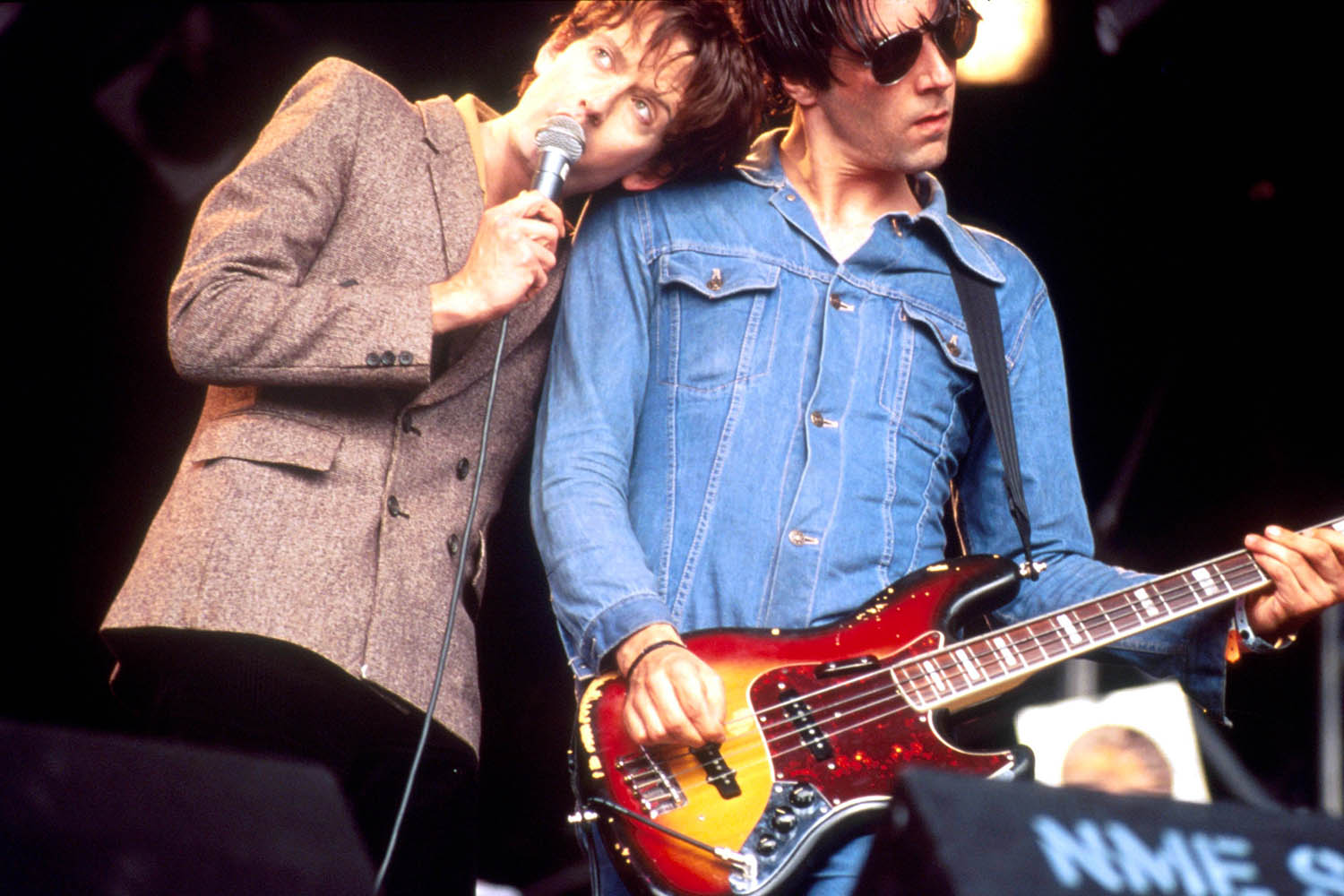

Photographs by Michale Putland, Redferns, Richard Saker