Photograph by Christaan Felber

Six years ago a man named John J Lennon – seldom has a middle initial been more necessary – published a piece in the New York Review of Books. It began: “On 10 February 2002, in a New York state prison cell, the bestselling author and twice-convicted killer Jack Abbott hanged himself with an improvised noose. That same day, the body of the man I murdered washed ashore on a Brooklyn beach in a nylon laundry bag.”

It was the kind of opening that any feature writer would, well, I was going to write “kill for”, but the emptiness of that cliche is brutally exposed by the experiences recounted in Lennon’s extraordinary debut book, The Tragedy of True Crime.

Lennon is serving a 28-year-to-life sentence for the murder in December 2001 of a friend and fellow drug dealer whom he believed to be robbing his clients. Having moved around a number of New York state prisons, he is at present in Sing Sing correctional facility, on the banks of the Hudson River north of New York City. That’s where I recently spoke to him on a long phone call.

In the background, I can hear the clang and shouts of prison life, the cacophony that has been an unrelenting feature of his life for almost 24 years.

“It’s the worst thing about prison,” he says. “I hate it and it’s nonstop.”

Incessant noise is not easy for anyone, but for a writer in search of peace to think, it’s a particular kind of hell. Nonetheless, it hasn’t prevented Lennon from becoming a contributing editor to Esquire and writing a succession of pieces for the New York Review of Books (NYRB), Rolling Stone, the Atlantic, the New York Times and others.

He has written about how the lack of gun control in the US feeds violent crime, about education in prison, and about the effect prison has on time and ageing. He’s written about pen pals and conjugal visits. And now he has written a near 370-page book that challenges the misleading tropes of the multimedia genre known as true crime.

Lennon had a tough start in life. Growing up in New York, he was abandoned as an infant by a father who later killed himself, joined a Hell’s Kitchen street gang as a teenager, was placed in juvenile detention, and then became a gun-toting drug dealer and addict in his twenties. So his is a story of literary redemption.

Except there’s just one problem, as Lennon recognised in his NYRB essay: Jack Henry Abbott. A lifelong criminal, Abbott had killed a man in prison, then escaped and robbed a bank, but also wrote powerful letters that convinced Norman Mailer, former NYRB editor Robert Silvers, and the actors Susan Sarandon and Christopher Walken that he was a reformed character.

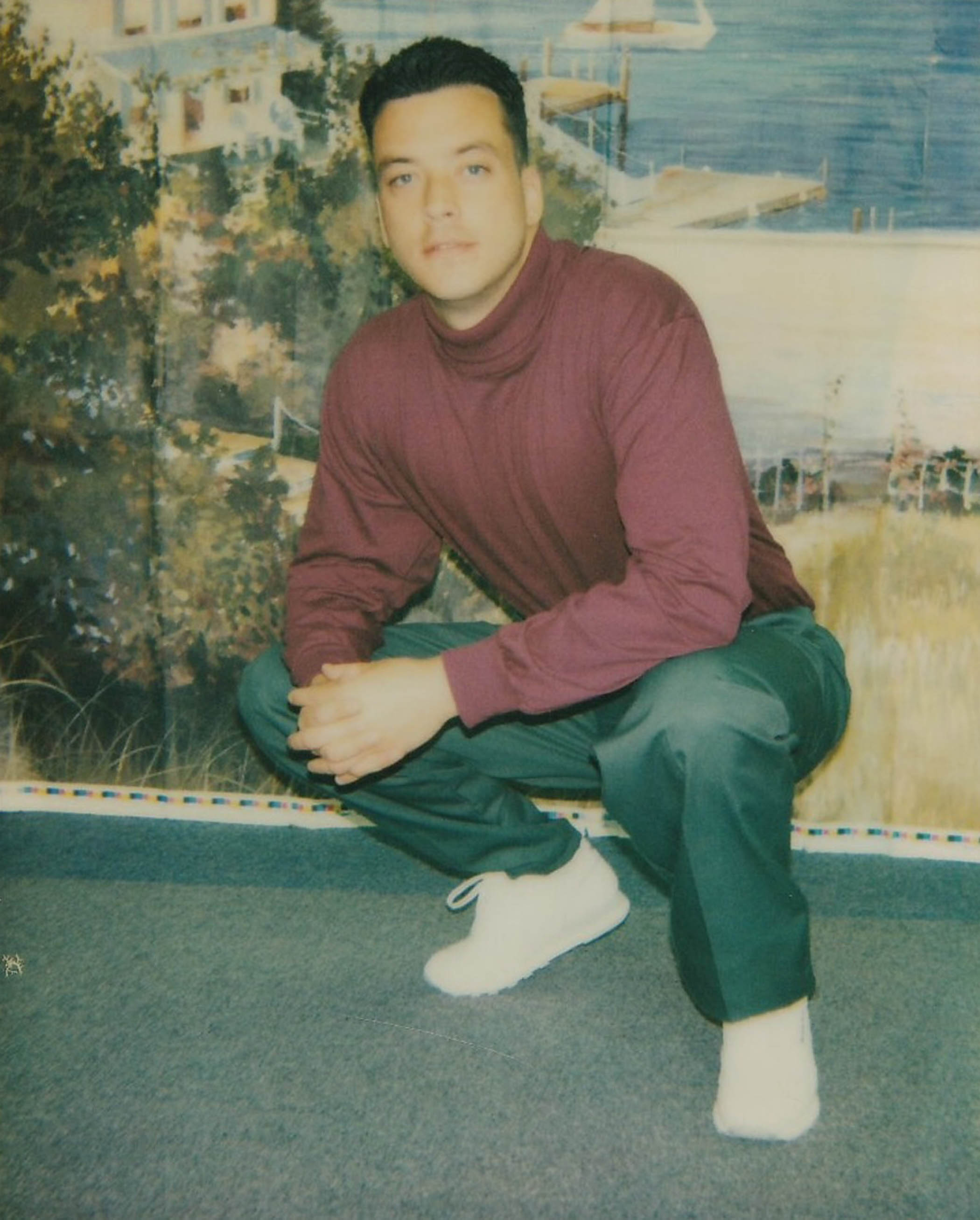

John J Lennon early in his incarceration. He is serving a 28-year-to-life sentence for the murder of a fellow drug dealer

With glowing testaments from Mailer and Silvers, he gained an early release in 1981, saw his collected letters published as a book called In the Belly of the Beast and, just six weeks into his freedom, stabbed to death a 22-year-old waiter and aspiring playwright outside a Manhattan restaurant.

“It’s been an albatross around my neck,” says Lennon of Abbott’s legacy. “Every time they talk about a successful prison writer, his name comes up.”

He resents the comparison for many reasons, not least their very different attitudes and styles.

“I think it’s pretty revealing on the page what he was about and how searing his anger was,” Lennon says. “I remember one sentence he wrote about COs [correctional officers]: ‘The only time they appear human is when you have a knife at their throats.’ I can’t imagine myself writing a line like that. It’s actually good writing but it’s a disgusting sentence.”

Unlike Abbott, who tried to mitigate his crimes by making unsubstantiated claims about the men he killed, Lennon is clear in his culpability and his remorse. The man he murdered was a fellow gangster who’d earlier been tried for (and acquitted of) murder: Lennon points out that it would be meaningless for him to make claims about his own change of character if he didn’t acknowledge that he denied his victim that opportunity.

Still, the lingering Abbott effect may be one reason why Lennon’s own appeal for clemency has so far left New York’s governor unmoved, despite the backing of a number of leading American journalists.

The Atlantic’s David A Graham wrote as part of the appeal: “I believe he has a bright future in professional journalism ahead of him.” Leann Alspaugh, managing editor of the Hedgehog Review, stated: “I see in John the qualities I would look for in a friend – trustworthiness, empathy, a desire to work and improve, a sense of humour, intelligence … We here on the outside need him – we need to see what rehabilitation looks like.”

Another factor working against Lennon, however, is likely to be that the sister of the man he killed does not accept that his repeated expressions of remorse and contrition are sincere. She has also requested that he desist from using her brother’s name in his writing (in the book he is referred to only as “E”).

At Lennon’s sentence hearing, E’s sister quoted the Harvard philosopher William Ernest Hocking on crime and punishment: “Only the man who has enough good in him to feel the justice of the penalty can be punished.”

Those words weighed heavily on Lennon as he came to learn that the more he recognised the far-reaching effects of his crime, the harder prison became. Accepting guilt is a recurring theme in his writing. But the writing is not simply cathartic; it, in turn, creates another layer of guilt.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“What gives my life purpose may be the thing that causes E’s family that much more pain,” he writes in the book. “I’ve often wondered whether I would have become a writer had I not murdered a man and gone to prison. Probably not.”

That is the fiendish paradox in which the prison writer is trapped: had he not killed someone, he would not have discovered the talent that gives his life meaning – and that talent only causes further suffering for the family of the man he murdered.

What’s the answer?

“I don’t know if I’ve figured out how to reconcile that,” he says. “Some questions don’t have easy answers.”

If guilt – the fact and emotion – is his literary preoccupation, then prison, he says, is filled with men who claim to be innocent. This is partly because it offers the only hope of a way out from the extremely long sentences – sometimes 50 years to full life – that are commonplace in American prisons.

“Those sentences are undoable,” he says. “So [the prisoners] often get lost in the law library, trying to find ways to challenge their convictions.”

He sympathises with that desire for freedom but he says that, as a journalist, he’s more interested in those men who try to come to terms with what they’ve done.

In The Tragedy of True Crime, Lennon looks at the plight of three killers he got to know and interviewed at length in prison. One is a gay man who killed his older lover, he claims after many years of domestic abuse. Another is an African American who, as a teenager, took part in the murder of two priests. Both these men are serving 50 years to life. The third is Robert Chambers, an Upper East Side child of privilege who, while still at school, strangled an 18-year-old female friend and gained tabloid notoriety as the “Preppy Killer” and was namechecked in Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho.

With his expensive lawyers, Chambers got a 15-year sentence, but became a junkie inside. After his release, he soon returned to prison with a 19-year sentence on drugs charges.

Around these three stories, Lennon also weaves his own tale. His aim is to step back from the lurid focus on criminal deeds that is the hallmark of true crime, and also address the before and after. He’s interested in the harsh or dysfunctional conditions that formed the killers, as well as the harsh and dysfunctional conditions in which they serve their time.

The idea came to him after he took part in a documentary about his crime that was entitled, much to his distress, Inside Evil. He felt misled by the producers and believes that both the killing and the pain experienced by E’s family were exploited for entertainment. E was an old friend, but a rival drug dealer, whom he shot dead with an assault rifle, having lured him into a car journey. He then unsuccessfully tried to dispatch the body to the bottom of the Atlantic at Sheepshead Bay. He says he partly committed the murder to prove to himself that he was a real gangster.

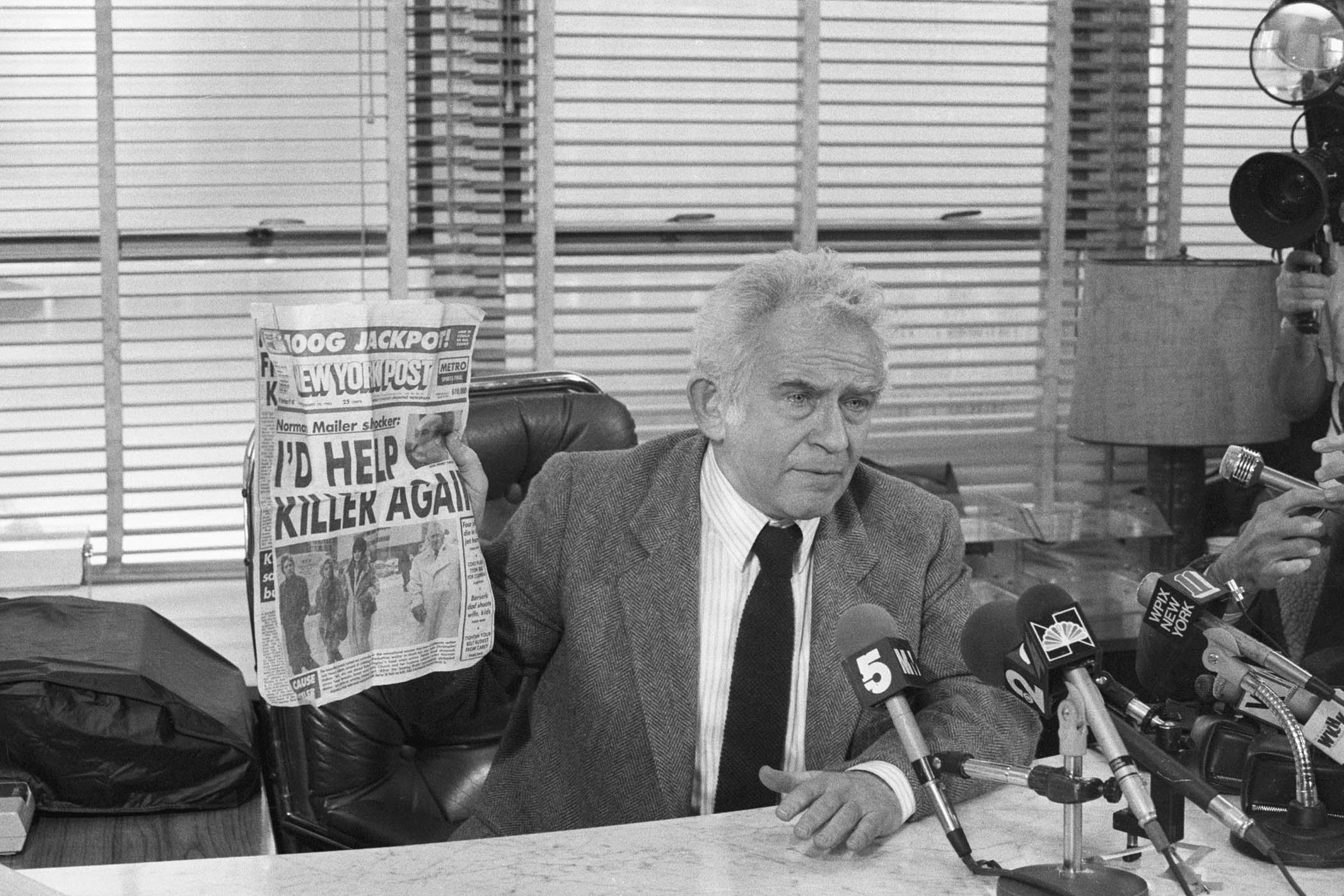

Norman Mailer, who was convinced that murderer Jack Abbott was a reformed character after reading his letters

“[The producers] weren’t interested in my crime until I started to get my act together,” he says. “It was a run-of-the-mill drug murder, not to diminish my culpability. There was a lot of unethical behaviour.” He sounds a little riled, but his way of dealing with that experience is not just to critique the explosion in the true crime books, podcasts and TV. He also seeks to demystify crime and show the long shadow lives of its perpetrators.

Of course, that in itself could be construed as self-serving, a mea culpa that is really another version of: “Society made me do it.” But as Lennon writes: “What happened to me growing up, as far as I was concerned, didn’t explain why I chose to run the streets and kill a man.”

Nor do any of the stories of the other three men lead inexorably to murder, but they do explain how each of them arrived at stress points, where that outcome grew dangerously more possible.

Having studied writers such as Gay Talese, who crafted his stories out of a lengthy research process, Lennon is at pains to find out all he can about his subjects, contacting their friends and family on the outside, as well as those of their victims. Although he was helped by external research volunteers, it’s no small achievement for a man without internet access and an electronic typewriter that only has about 1,000 words of memory.

Lennon no longer thinks of himself as a criminal. But when he was first imprisoned, he was quite upfront about introducing himself as a murderer.

“You [have] to show your paperwork,” he explains, “show that you didn’t kill a woman or do something to a child. There’s a pecking order here.”

His attitude began to change when he was attacked by a friend of E’s in Green Haven prison, who stabbed him six times with an ice pick and missed his heart by an inch. For refusing to identify his assailant, Lennon was transferred to Attica, known as the “worst prison in New York”. It was here that he joined a creative writing workshop and “learned to live with what I did, on the page”.

He also began reading voraciously. There were many books – Albert Camus was an early influence – but as they became harder to access, because of tightening prison rules, he turned to magazines, about which he became obsessed.

Nowadays, Lennon prefers to identify himself as a journalist. He believes that writing about his past and about the struggles of prisoners like himself has helped him “develop the thing I’ve always lacked: empathy”.

Every prisoner has to negotiate a line between the rules of the system and the code of the yard. It’s a task that can seem like walking a tightrope if you also become a working journalist, with the potential to provoke both sides. “Journalists are curious, sometimes a bit nosey, and asking questions is something you probably shouldn’t do when you go to prison,” he says.

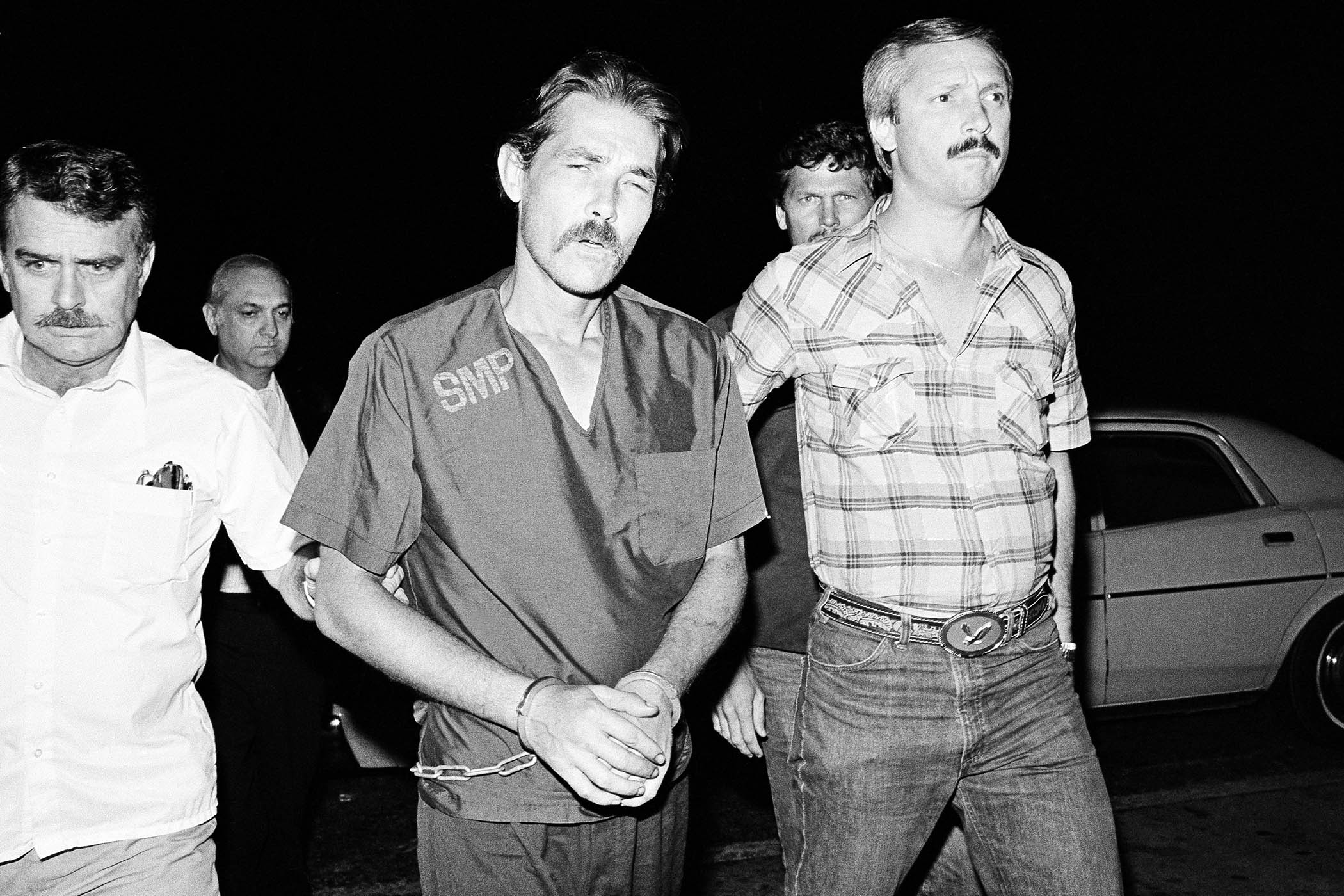

Abbott, centre, killed again six weeks after his release

The feedback he’s received from fellow prisoners on his work has been varied, depending on the subject matter. One piece he wrote about mental health – it’s no coincidence that the closure of psychiatric units in the US was accompanied by a huge rise in prison population – went down well, but no one stands on ceremony because he’s got a byline.

“One time a guy tried to extort me and I was on a deadline for the New Yorker. I was like: ‘Get away from me, I have a deadline.’ You know, I’ve outgrown this bullshit.” I say I have difficulty imagining how the line: “I’m on a deadline for the New Yorker” would go down in prison and he bursts out laughing at the absurdity.

Should we be more sympathetic to prisoners who take up intellectual work, the kind that conventionally marks a person out as bourgeois, cultured, civilised? There’s a scene in the book in which Lennon recalls his court case, and how, before the jury arrived in the morning, the lawyers from either side would greet one another and exchange pleasantries. It’s in these moments, he writes, that “the murderer feels most like a stranger to humanity”.

All the subjects of Lennon’s book live with that estrangement, just as their victims’ families live with another kind of estrangement – the irreversible separation from their loved ones. Lennon leaves the reader in no doubt that the killers must bear the responsibility – and the punishment – for their crimes. But he also believes there is a point at which the punitive aspect of a sentence serves no further purpose, other than to destroy the person serving it. His neighbour in prison has been inside for 43 years and can only walk with a cane.

“We’re real serious about our punishment in America,” Lennon says. “We’re not playing any games.”

One of the few physical connections to the outside world available to inmates are occasional conjugal visits – but only with spouses. Lennon has married twice during the course of his sentence to women he met through Friends Beyond the Wall, the prisoner pen pal organisation in the US. Neither marriage has survived.

I ask him: what’s in it for the women?

“Oh, that’s dangerous territory, to ask me to speak for women,” he laughs. “Neither of my wives was cruising the internet looking for men in prison. But often, it’s a safe relationship that’s not controlling and some of the women may have got out of toxic relationships. What became problematic for me is that I started being very involved in my career.”

He is fully aware of the irony of being a middle-aged man married to his work. “That’s why I’m single and alone,” he says, “but I have my writing.”

The great majority of murderers who’ve served the length of sentence that Lennon has do not kill again. Abbott was a damaging exception – an impulsive killer with a compelling gift for blaming society.

While Lennon doesn’t shirk his personal responsibility, he does believe his crime was social rather than pathological; the rotten fruit of a certain milieu, lifestyle, age.

“I’m pushing 50 years old and I think very differently to [when I was in] my 20s. I’m not a criminal just because I live in a cell. If a detached politician doesn’t acknowledge that, it’s not my problem. I’m going to live a life, I am going to be a successful and a decent human being, and that’s that.”

He sounds like a man who’s eager to catch up on what he’s missed out on. He dreams of being able to pursue subjects beyond the confines of a prison, of testing his abilities against journalists who can travel freely. Going on his book and published journalism, he obviously has the writing skills. Does he have the life skills?

As punishment rather than rehabilitation is the main focus of the prison system in which Lennon has been held for 24 years, there is only one way to find out.

The Tragedy of True Crime by John J Lennon is published by Castle Point Books (£25.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £23.39. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images, AP