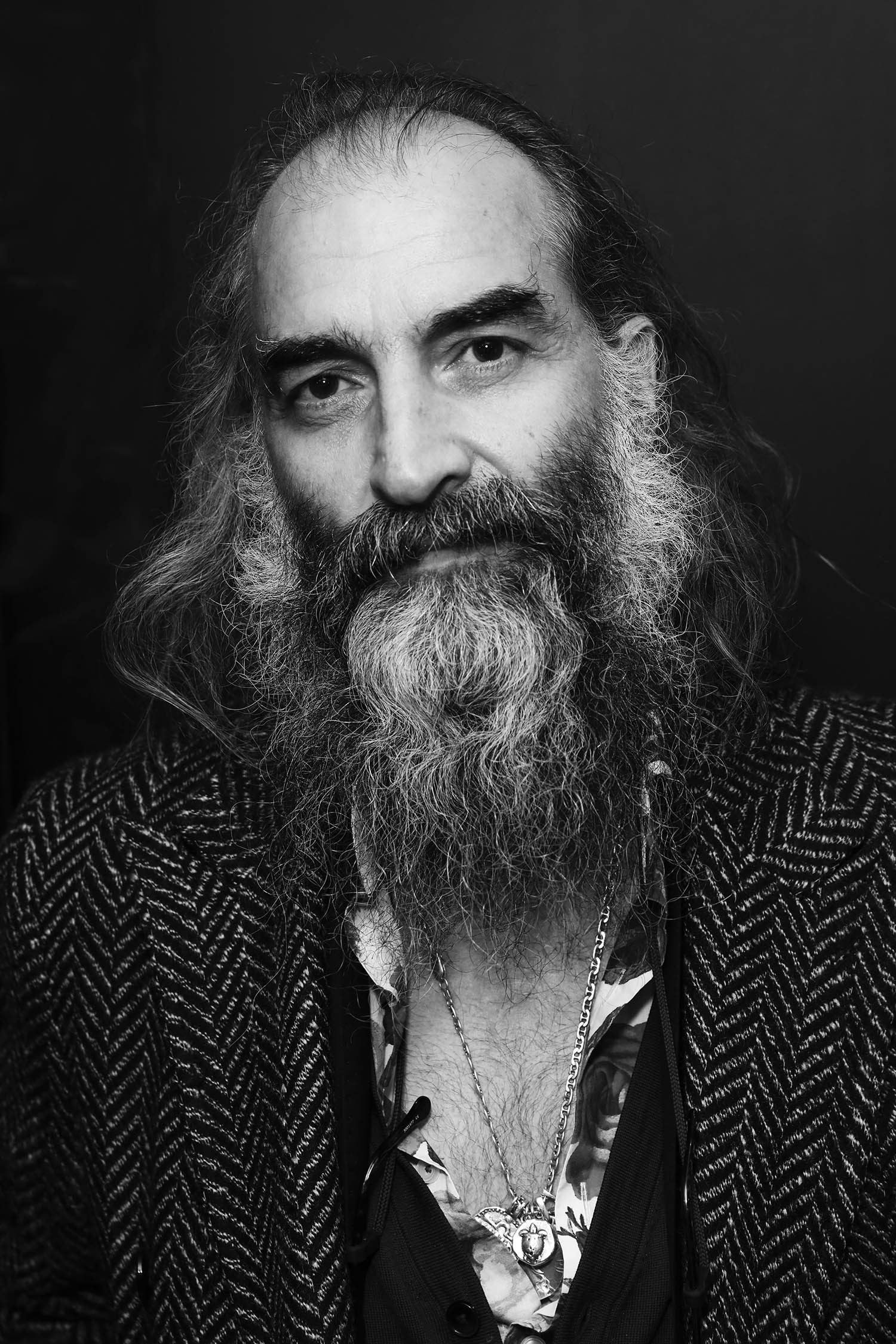

Warren Ellis, 60, is an Australian musician, composer and author. He co-formed the Dirty Three in 1992 and has been a full-time member of Nick Cave’s band, the Bad Seeds, since 1997. Ellis has composed several film soundtracks with Cave, including Blonde (2002) and The Road (2009). In 2021, Faber published Ellis’s debut book, Nina Simone’s Gum: A Memoir of Things Lost and Found. The same year, Ellis bought a plot of land in Sumatra and donated it to the Jakarta Animal Aid Network, which rescues animals that have been held in captivity and cannot survive in the wild. A film about the project, Ellis Park, directed by Justin Kurzel, is released on 26 September.

How did the Ellis Park project come about?

I was introduced to Femke den Haas, [co-director of the Sumatra Wildlife Center] and that was it. Femke is answering a calling: she saw an orangutan chained up and she had it released and, in that moment, her life changed. Everyone who works there is compelled to do what they do. Their motives are pure. They don’t want kudos or praise. Initially I thought of it as simply the right thing to do, but it has changed me in a deep and profound way.

Can you elaborate?

I just think that when love, compassion and trust are in place, it makes for a better world. For me, the park is symbolic of that. Personally, as I’ve become older, the idea of being at peace with myself has become more important, and this project has been a big part of that journey.

The film follows you on your first visit to Sumatra and the animal sanctuary. Were you prepared for that experience?

Oh man, I was so not prepared, but I don’t think you can ever really prepare for an experience like that. I’d come off the Carnage tour with Nick, spent a month looking after my dad, and then jumped on a plane to Sumatra. Thankfully, my son took me aside and talked me through the practicals: water purification pills, shots, a pair of shorts.

It was a real trek to get there and the jungle gets wild pretty quick. The heat was intense, there were snakes and, at one point, I almost got killed by a falling coconut. So, it was pretty wild at times, but also restorative. I had this little house in the jungle and I’d wake up to the call for prayer at sunrise, the monkeys chattering, and the mist rising. I experienced a kind of peace I had never felt before.

Rina, a monkey whose arms had both had been amputated, is a totemic presence in the film, but she did not take to you.

No, she hated me. I thought I would play the violin and soothe her soul but she just leapt over the keeper and went for me. I could hear the producer shouting, “Get him out now!” It was pretty scary.

How did you get on with the director, Justin Kurzel, who is best known for his brutal feature films [such as Macbeth with Michael Fassbender]?

I said to him: “Just make the film you want.” But that was after I’d tried to stop it a few times. Making it was like having years of therapy condensed into a few days.

In one section of the film, Kurzel also travels with you to Ballarat in Australia, where you grew up. It seems like a place that holds many conflicting memories for you.

Initially I had deep reservations about that part. It was deeply personal and I have no interest in baring my soul. I’m a musician, I don’t write lyrics; so no one is trying to judge or analyse what I say. Writing the book [Nina Simone’s Gum] was challenging in that light, but also brilliant – but I did feel like an imposter for a time.

What was it about the Ballarat section of the film that concerned you?

Well, it set off a lot of alarm bells because my family situation is complicated, especially my relationship with my mum, and that caused me a lot of trepidation. But Justin’s film hints at that rather than spelling it out. The idea of me going back to Ballarat was never scheduled; we just did it. It affected me deeply to revisit all those places I used to escape to as a kid. It was a way to settle some things, to find peace with all that stuff that had been hanging over me. It was a defining journey and one that has determined my life since. For a long time, I thought of my work life and my other life as two very different things. But now they feel like one and the same journey.

Your father, John, comes across as quite a character in the film. At one point, you duet with him on one of his songs.

My dad was always away with the fairies, as they say, but I think he got what I was doing. He grew up poor: a wooden shack, earth floor, holes in his shoes. But he always spoke with such curiosity about things. He was creative but he had to shut his dreams down in order to bring up his family. I spent some time with him before he died and that was profound. I settled some things and found peace with some stuff that had been hanging around for ever.

How do you feel about the film now that you’ve had time to process it?

For me, it’s an extension of the idea of communal imagination: if you dream it, it will happen. It’s about having faith in yourself and your ideas. I’ve realised that the uncomfortable place you find yourself in is often the best place to be. That also applies to making music. Your better logic might tell you not to follow certain ideas that seem a bit too out there, but they can often be the ones that matter. The thing is to just keep going and work through it because even if it doesn’t work, it’s productive. You have to make the leap.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photograph by Darren Gerrish