William Kentridge x Philharmonia Orchestra: Shostakovich 10

Royal Festival Hall, London SE1

Tom Morris x London Philharmonic Orchestra: Mahler 8

Royal Festival Hall, London SE1

Igor Levit: Vexations

Queen Elizabeth Hall, London SE1

A promise, or was it a threat, ahead of the Southbank’s Multitudes festival was that we would experience “sensory saturation”. This 10-day event was an invitation to discover orchestral music “for all the senses”. With the merciful exception, most of the time, of smell, the great works of the repertoire deliver that anyway. But let’s set quibbles aside. The idea was ambitious, full of experiments that did not necessarily work but provoked interest and, as far as it’s possible to gauge, drew new crowds. If opera is the crucible in which all art forms fuse to create a new unity, here was the opposite.

Dance, film, video and circus were skilfully grafted to particular pieces of music but remained resolutely distinct: an engrossing William Kentridge film premiere created specifically to accompany a Shostakovich symphony; Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé performed alongside breathtaking acrobatics; Mahler’s “Symphony of a Thousand” No 8, with abstract video and movement to try to give clarity to the composer’s opaque setting of Goethe’s Faust. However beautiful or stimulating, these hybrids of sight and sound remained as unresolved as mythical beasts, half-and-half curiosities to see once and wonder.

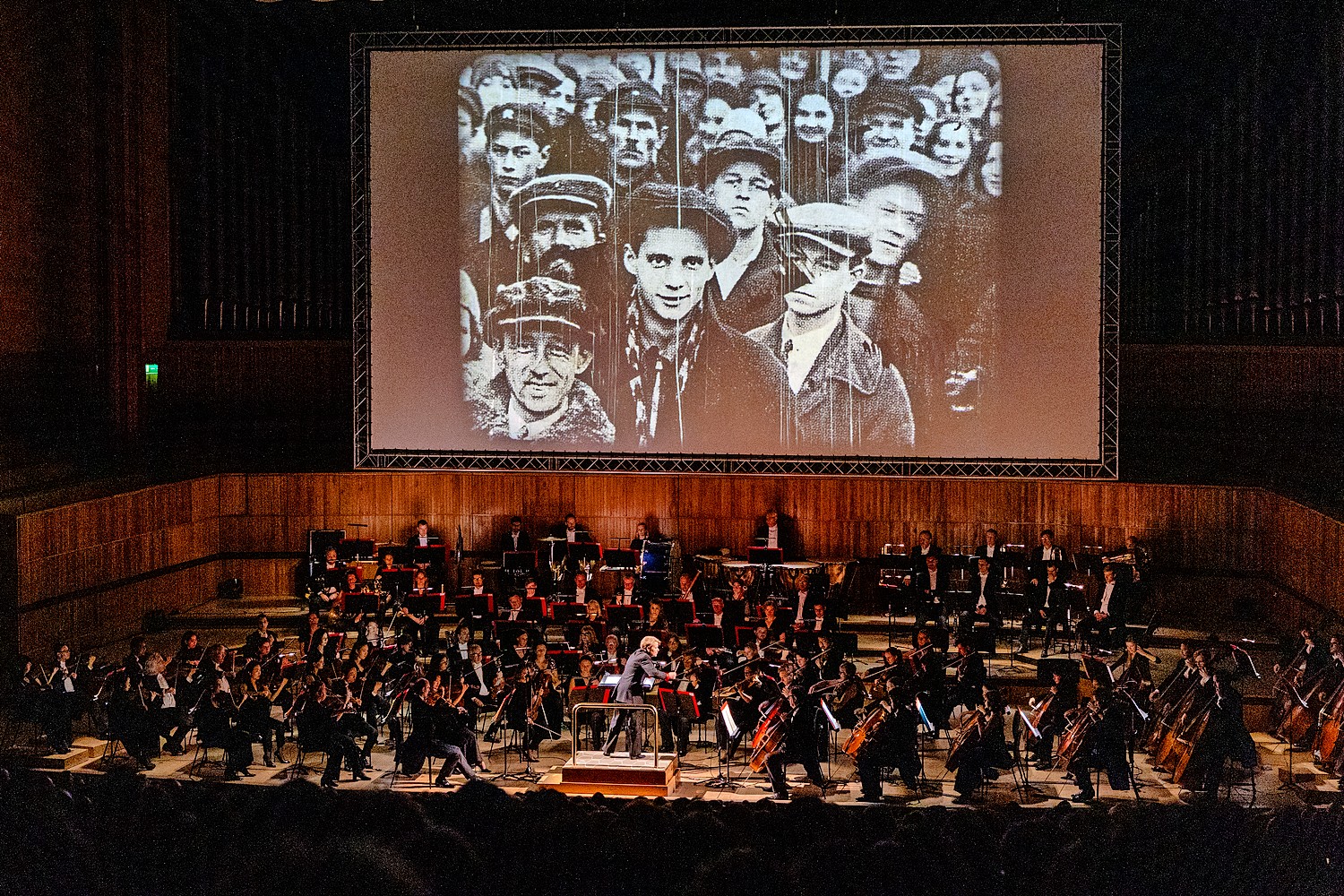

The prospect of Marin Alsop conducting the Philharmonia in Shostakovich’s Symphony No 10 in E minor (1953) was in itself a draw. The programme opened with Chichester Psalms, among the most popular works by Alsop’s great mentor and inspiration, Leonard Bernstein. Sixty years old this summer, this three-part choral and orchestral psalm setting was commissioned by one of the last century’s quirkily brilliant patrons of music and art, Walter Hussey, then dean of Chichester Cathedral. (Benjamin Britten, William Walton, Marc Chagall and Henry Moore all benefited from his visionary support, as did Chichester’s Pallant House Gallery.) Energetically and rhythmically performed by the Philharmonia forces, with notably expressive playing by the pair of harps, this was an unexpected but rewarding prelude to the Shostakovich.

Completed soon after the death of Stalin, whose regime had cast such a shadow over Shostakovich, the composer’s Symphony No 10 haunts from the start. In the long, slow opening movement, clarinet, flute and bassoon sing out in mournful despair. The Philharmonia captured the mood of lament, snapping and snarling through subsequent march and waltz, and embracing the outbursts of fortissimo anguish and tragedy. In his 2022 film Oh to Believe in Another World, the South African artist Kentridge (b1955) has delved into Shostakovich’s complex biography, freely reflecting aspects of the Tenth Symphony.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The setting is a museum, colonnaded, with stuffed historical figures, as well as a Soviet-era, white-tiled swimming pool. Using a miniature camera, puppets, collage and actors, he creates a detailed landscape via the familiar figures of Trotsky, Lenin and Stalin. I was entranced by the many-layered film, and gripped by the music, but never by both at the same time. The only way for Shostakovich’s music and the excellent musicians not to feel like a soundtrack was to shut my eyes, which somewhat defeated the object. Still, it was an intriguing event.

These hybrids of sight and sound remained half-and-half curiosities to see once and wonder

These hybrids of sight and sound remained half-and-half curiosities to see once and wonder

The semi-staging of Mahler’s Symphony No 8 was where sensory saturation, despite serious efforts by all, got the better of sense. With hundreds of choral singers – the combined forces of the London Philharmonic Choir, the London Symphony Chorus and Tiffin Boys’ Choir – with vast orchestra (the London Philharmonic Orchestra at their impressive best) and eight soloists, you could argue there was quite enough action already. Edward Gardner, conducting, squeezed every iota of feeling out of this sprawling score, urging his populous forces to give their all, which they did. Tom Morris (War Horse) directed, but even this admired man of the theatre could not make Mahler’s mix of a sacred medieval hymn and the final part of Goethe’s Faust any more comprehensible. The addition of video screens (video artist Tal Rosner), showing beauteous, gaseous emissions, a naked man and a sequence of intergalactic starscapes, added a further ungraspable but attractive strand. Mahler might well have loved it.

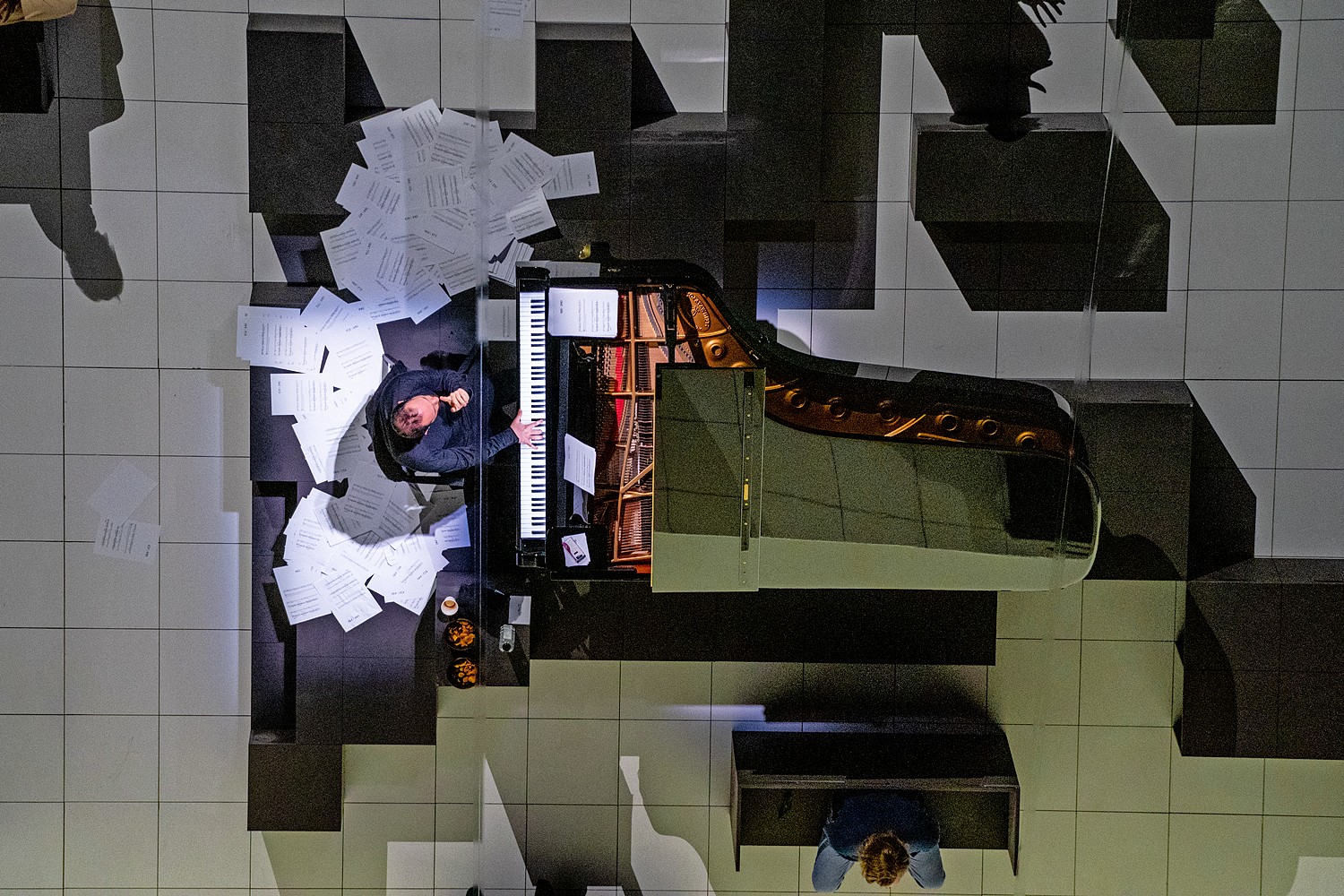

That same day, starting at 10am and ending soon after 11pm, Igor Levit played Erik Satie’s Vexations, repeated 840 times, staged by Marina Abramović. Much has been written about this epic endeavour already, largely concentrating on Levit’s bodily needs, reasonably enough. Having heard large sections when he performed it online in lockdown, I wasn’t rushing to sample it again. Yet the draw proved irresistible. Levit, a disciple of long-form music, is a player of such invention that he could make this same single page of music embrace entire worlds of pianism, now Beethoven, now Cage, now Satie. The physical prowess was incredible, but Levit’s tireless musical imagination was the real miracle.