Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run was released 50 years ago this week and if ever there was a record that deserved commemorating, it’s this one. It arrived, unheralded, in a desperate period for rock music. The likes of Elton John and Led Zeppelin were dominating the album charts and the Rolling Stones had become (as they have remained) a tribute band to themselves. When the coke-addled David Bowie wasn’t trying to be a film star, he was lurching from plastic soul towards electronic music. We needed heroes all right but they were years away. Punk was starting to make loud, discordant noises in the basements and garages of the Bowery and Hammersmith but nothing coherent had emerged yet. And then came Springsteen.

After two unsuccessful albums, the latest “new Bob Dylan” seemed to have missed his chance. So when a concert reviewer in an obscure Boston weekly, the Real Paper, declared that he “had seen rock’n’roll future and its name was Bruce Springsteen”, the prophecy attracted sneers, not cheers, from the sophisticates of the all-important British music press. But that reviewer, Jon Landau, who went on to become Springsteen’s manager and sometime producer, was on to something.

In the autumn of 1975, I was 18 and had taken a job as a live-in teaching assistant in a remote Kent school just to be near the girl I loved. She had, with crushing insouciance, dumped me before I turned up (late) for my first day.

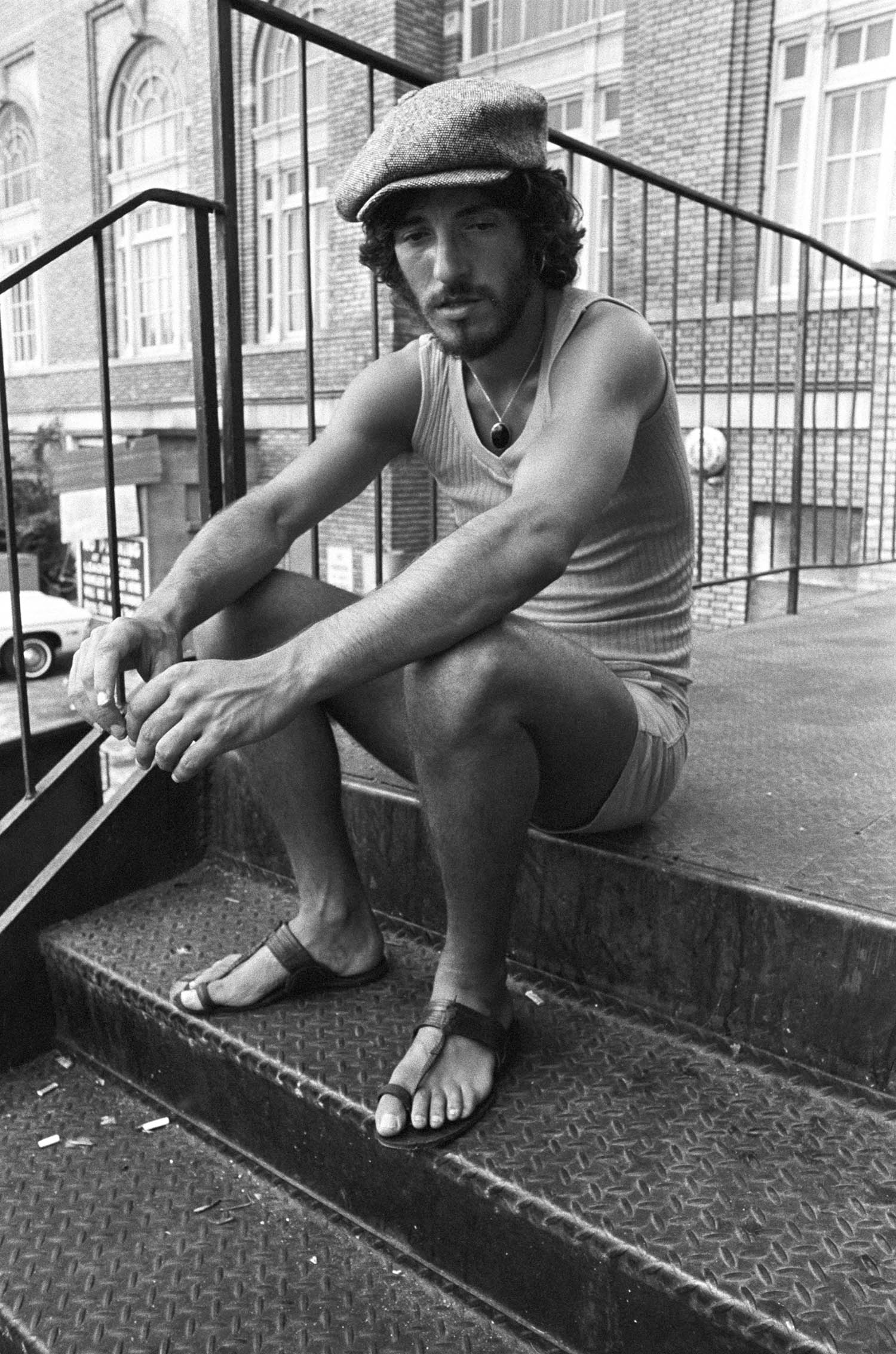

‘All I had going for me was a transistor radio, a record player, and a handful of albums’: Keith Blackmore at age 18, in the summer of 1975

My work colleagues were all at least a decade older than me and my new boss thought, not without reason, that I was a sulky trouble-maker. I was not only heartbroken but also extremely badly paid, even by the standards of the times.

When the staff and pupils went home each day, I was left alone but for a couple of Spanish caretakers, neither of whom could speak English. In the days before the mobile phone or the internet, civilisation was a complicated series of bus rides away. After each interminable day teaching unruly 10-year-olds badly in a temporary classroom, I was learning my own hard lesson about loneliness.

All I had going for me was a transistor radio, a record player, a handful of albums and a picture of David Bowie taped over a bad landscape hanging on the wall.

One evening, however, amid a lot of dispiriting dross, a thrilling new single crackled out of that radio. It was so good I wondered if I’d heard it before. Even its title seemed familiar. But it was new. By an artist with a strange and memorable name.

So one night, after ensuring the last small figure had been gathered from the playground by a tardy parent, I was desperate enough to take those complicated bus rides. The small town record shop I entered just as they were trying to close didn’t have that single. But it did have one slightly marked copy of the album of the same name. I took the complicated bus route home and, for the first time but not the last, a record saved me.

Born to Run’s romantic vision of escape from drudgery was exactly what tramps like me were seeking

Born to Run’s romantic vision of escape from drudgery was exactly what tramps like me were seeking

The gatefold sleeve of Born to Run is now justly famous in its own right. Eric Meola’s black and white photograph of a white man and a black man, artfully arranged to suggest a lifetime of interracial friendship, was mildly daring and about as cool as it was possible to be in 1975. But that wasn’t even the best thing about Born to Run. That would be the songs.

Not all of them, of course. My rule of thumb is that a great album must have at least two great songs. A handful, mostly by Joni Mitchell, have more. Born to Run has four.

The first to make its greatness known to me was Meeting Across the River, a song seldom mentioned today, even by diehard fans. It was the B-side of the single that had attracted me in the first place.

Against Randy Brecker’s mournful trumpet solo and Roy Bittan’s tinkling, late-night barroom piano, Springsteen gives us a vignette of failure. The 27 succinct lines of the song tell a film’s worth of story (it was originally titled The Heist) as we hear a desperate young hood try to persuade a friend to join him on an ill-conceived and obviously doomed robbery.

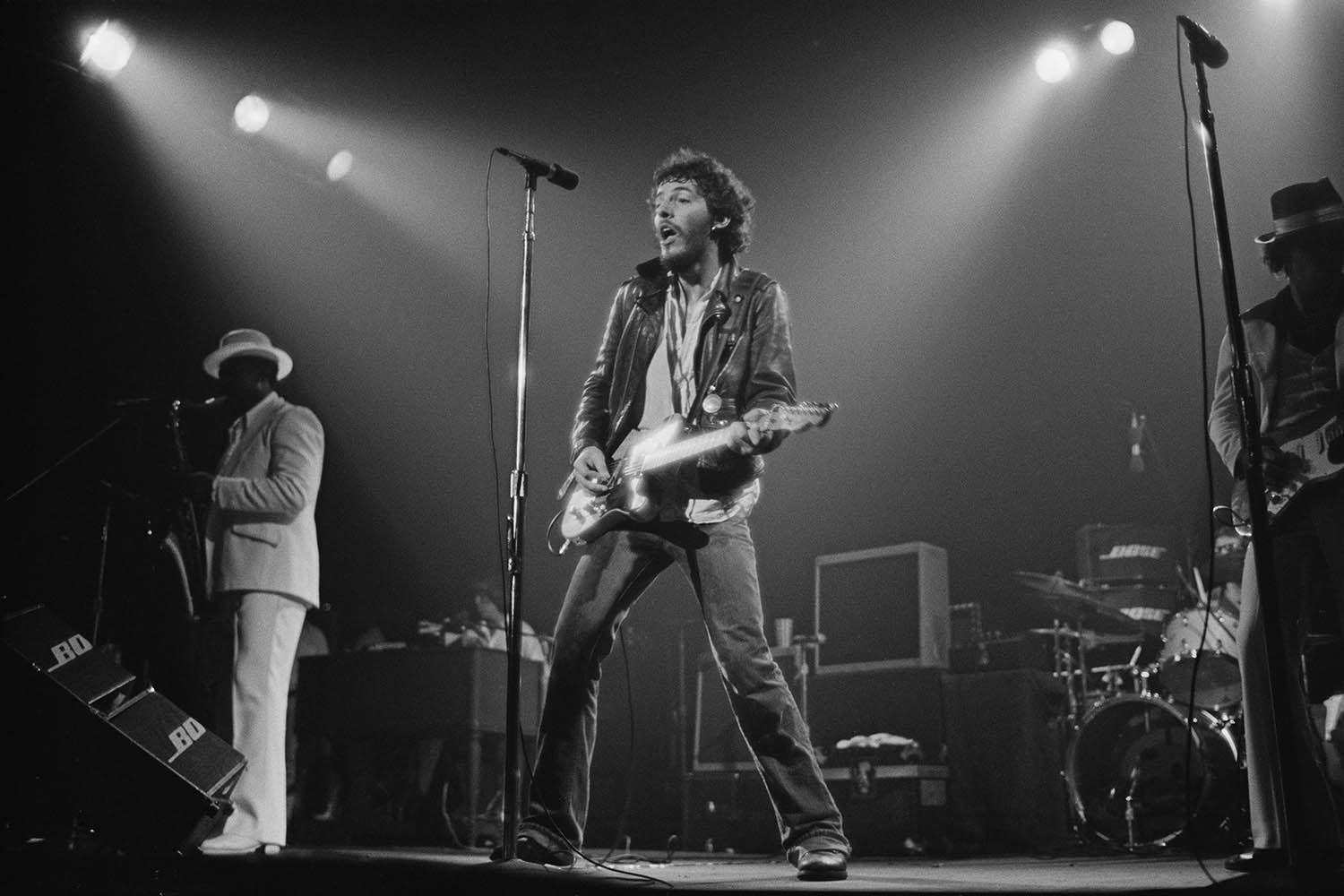

Bruce Springsteen takes a break from soundchecking during the Born to Run tour in Atlanta, 1975

He promises that when the deed is done, he’ll just throw that money on his girlfriend’s bed. Not hard now to see why that would have appealed to me so much then.

Similarly, Backstreets, with its depiction of a suffocating romantic betrayal, could hardly have been better designed to pierce my self-regarding gloom. It also contains some of Springsteen’s best writing: “Remember all the movies, Terry / We’d go see / Trying to learn how to walk like the heroes / We thought we had to be.”

The first time I heard the third great song, Born to Run – the one that put me on the buses – was through that transistor radio, exactly as it was designed to be heard.

It jumped out of the tiny, tinny speaker like a firecracker. And its romantic vision of escape from failure and drudgery was exactly what tramps like me were seeking, even if it was not entirely clear where we would be going.

Nothing I’ve heard since tops the thrill of hearing for the first time Springsteen counting back in his band as the song reaches its thunderous crescendo.

Which brings us to the fourth great song, the album’s opening track. I contend that Thunder Road is the peerless love song in all rock music; it is certainly Springsteen’s best. For many years, though, I thought it was purely romantic: a bid to persuade Mary to run away with him to a happier life.

Then a woman friend told me firmly that the song was in fact about sex. This set me back. After long consideration (“You know just what I’m here for”) I have come to see she might have been right. Or at least that it is about romance and sex.

In any case, it has always seemed perfect to me, right from its brilliantly realised opening (“The screen door slams / Mary’s dress sways”) to its thrilling end (“So Mary climb in / It’s a town full of losers and I’m pulling out of here to win”). And it has gone on revealing its meanings for 50 years now.

Springsteen actually wrote a sequel to Thunder Road but for years declined to release it. The Promise, which can be found on bootlegs and, these days, rerecorded, in his official canon, is a song about disillusionment, written in the late 70s when he was trapped in a legal bind and unable to record or perform. It’s powerful – “Lived a secret I should’ve kept to myself / But I got drunk one night and I told it” – but bleak, with Thunder Road being explicitly depicted as a road to nowhere.

That leaves four other songs. One of them, Jungleland, is famous and beloved but makes no sense to me (great sax solo by Clarence Clemons, though) even if a tenuous case can be made for it completing the story begun by Thunder Road.

Both Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out and She’s the One are boisterous, fun and nonsensical. Both are frequently performed by Springsteen today without carrying much weight. The remaining song, Night, is filler.

I still have that first copy of the record, with its evidence of my attempts to remove the mark on the sleeve and, for collectors, the important misspelling of Jon (not John) Landau’s name on the back. I also have remastered and extended versions, a 30th anniversary edition, bootlegs of early demos and every other iteration I have chanced upon. But there is one copy I treasure above all others.

In June 1981, on Springsteen’s first extended tour of Britain with the E Street Band, he walked into Harrods looking (incongruously) for a pair of swimming trunks. My friend Eleri, a Springsteen fan, was working there. She pointed him in the right direction and then rushed upstairs to the record department to grab a copy of Born to Run. Risking instant dismissal, she asked him to sign it. He did, taking evident care in spelling a tricky name right. Eleri died from cancer more than 20 years ago and her record somehow came to me. That’s the one I play, remembering her and the lonely boy Born to Run rescued 50 years ago.

Photographs by Redferns/WireImage

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy