Seventy years after his death in 1955, age 48, George Platt Lynes is arguably America’s least well known important photographer, a larger-than-life figure whose cultural status is undergoing a belated reappraisal as an artist and a pioneer of queer photography.

In the 1930s, he was an accomplished portraitist – his subjects included Tennessee Williams, Igor Stravinsky, Orson Welles and Dorothy Parker – and one of the most celebrated fashion photographers in the US, whose work appeared regularly in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar.

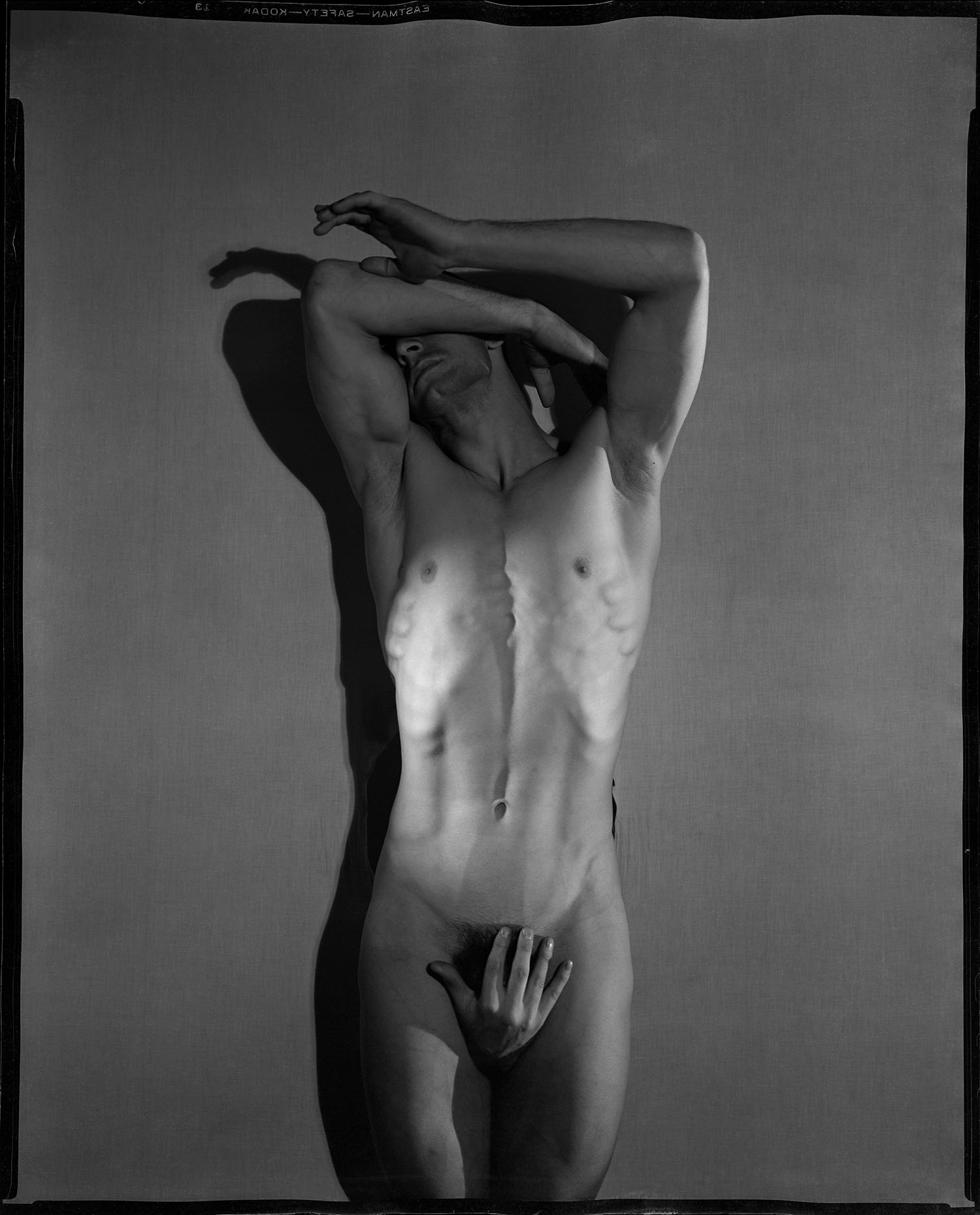

Unbeknownst to all but his close circle of gay friends, though, he was simultaneously creating a secret archive of provocative male nudes, their often explicit sexuality so at odds with the censorious morality of the time that, had they been discovered, he risked arrest and imprisonment. For several decades after his death they remained unseen, but they have led to an ongoing repositioning of his life and legacy (though there is yet to be a major retrospective of his work). They range from classically-inspired tableaux featuring dancers from the New York City Ballet to more overtly sexual portraits of the friends and acquaintances he persuaded to undress for his camera and more personal images – often closeups – of intimate love-making.

“He was a pioneer who did not live long enough to overcome the prejudices of the era in which he worked,” says Sam Shahid, director of a documentary film, Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes, which is released in the UK on 11 July. “For a long time, he was invisible to the mainstream, but he influenced so many photographers, from Robert Mapplethorpe to Bruce Weber and the late Herb Ritts, who loved his work.”

Shahid first realised Lynes’s importance when he was commissioned by the publisher, Rizzoli, to design a coffee table book, George Platt Lynes: The Male Nudes, published in 2011. “There were maybe 300 images that George had given to the Kinsey Institute and they were a revelation. I just immediately thought, ‘My God! What an artist. The world should know who this man is.’”

So began a labour of love that took almost ten years to complete. Drawing on the often colourful anecdotes of those who knew him, as well as the testimony of curators, collectors and contemporary photographers, the film delves into the artist’s extraordinary double life. It is a story of privilege, ambition, innate artistry and singular self-belief. But, perhaps most importantly, it is a portrait of a self-taught photographer who seemed supremely confident that the world would one day acknowledge his importance.

George Platt Lynes was born in East Orange, New Jersey in 1907. His father was a rector of an episcopalian church and his mother a teacher, who was fascinated by the experimental modernist literature of the time. It was through her literary connections that, during his initial sojourn in Paris aged 18, he befriended the writer Gertrude Stein and her partner Alice B Toklas. (Lynes’s formative ambition was to be a publisher, but his sole achievement in the field was to publish a small edition pamphlet by Stein titled Descriptions of Literature.) On his return to America to study at Yale, he wrote to Stein and Toklas to say how much he missed Paris and how his Ivy League education was “dull and stupid … intellectually timid … and infuriating” in comparison.

In 1926, he met the American author Glenway Wescott and publisher Monroe Wheeler, with whom he formed a long-term romantic threesome and embarked on an extravagant lifestyle of socialising, wild parties and, for the time, freewheeling sexual adventurism. In the film, Lynes’s biographer Allen Ellenzweig explodes the myth that, as he puts it, “before Stonewall, everyone was in the closet”. Lynes and his privileged social circle were both out and in, writing their own rules and, as many of his notebooks attest, recording their encounters, cultural and sexual, in letters and risqué images.

It was Wheeler who gave Lynes his first state-of-the-art camera, having been impressed by some of his snapshots. Lynes immediately began photographing the world around him with an effortless facility for composition and lighting. He had happened by accident on his creative metier and, having returned to Paris, made evocative black-and-white portraits of many of the city’s major creative figures, including Stein, Jean Cocteau, André Gide and Colette.

By the mid-30s, through sheer force of will and his considerable charm, he had established himself as a fashion photographer in New York, shooting subtly-lit and formally adventurous portraits of actresses, including Katherine Hepburn, and famous models such as Lisa Fonssagrives, who would later become Irving Penn’s wife. “I love George Platt Lynes’s fashion pictures,” photographer Bruce Weber tells Shahid, before succinctly summing up their strange appeal. “They are so odd and beautiful and there’s always an edge.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Having relocated to Los Angeles in 1946, Lynes continued to work for Vogue and also made a series of starkly atmospheric portraits of emigre writers such as Thomas Mann and Christopher Isherwood, whom he befriended. He also photographed several elaborately staged male nudes of dancers from the New York Ballet that hint at the more personal work that has surfaced since.

By the late 40s, Lynes had returned to New York, but his star was no longer in the ascendant as a new generation of fashion photographers emerged, including the likes of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon. (By then, ironically, Avedon had taken on Lynes’s former studio on East 49th Steet, which may have prompted Lynes to bitterly dismiss his and Penn’s work as “the all-time low in formula dreariness”.)

Lynes’s decline was as dramatic as his rise, his commercial career ending in bankruptcy and financial hardship. He burned many of his early portraits and reiterated his oft-expressed disdain for the fashion industry. “I’ve usually done my best work when I’ve worked only for pleasure, have not been paid, and had a completely free hand… ” he elaborated. During his final years, he bequeathed his archive of male nudes to the Kinsey Institute, founded by the pioneering sexologist Alfred Kinsey, where it remains.

No one in Shahid’s film really explains the reason Lynes disappeared from photography history for so long and why his moment may finally have arrived. The writer and curator Vince Aletti comes closest when he says: “There is a way for him to be appreciated now that didn’t exist 10 or 20 years ago, and certainly not when he was living.”

He remains an elusive figure, whose extravagant life is documented almost exclusively in still images. The exception is a nine-second fragment of Super 8 footage of him chatting and laughing with Isherwood, filmed by the latter’s lover, Don Bachardy, in New York in January 1955. Lynes looks animated and debonair, if a little self-conscious. In December of that year he died from lung cancer.

Mary Panzer, an art historian and curator, says: “He was a creative genius propelled by his aesthetic imagination, his need to suppress his gay identity, and his need to express it… and that ground him down until he expired of a broken heart.”

George Platt Lynes is long overdue for a major retrospective that draws together, and sheds light on, the conflicting strands of his singular journey. Hidden Master is a good place to start.

Photographs courtesy of the estate of George Platt Lynes