When Dennis Morris was a teenager growing up in Dalston in east London, his obsession with photography was such that his friends nicknamed him “Mad Dennis”.

“Just wandering around taking photos was enough for them to think I was odd,” he recalls, “but I instinctively knew it could be a way to step out of my environment and do something creative with my life.”

Morris had first been given a camera aged eight. A year later he started attending a weekly camera club in the vicarage of St Mark Dalston. It was overseen by one of the church’s benefactors, a local businessman called Donald Paterson, who had amassed a fortune producing high-end darkroom equipment.

“Most of the other kids just used the camera club as a way to get out of the house for a few hours,” says Morris, laughing, “whereas I couldn’t wait for Thursday to come around. I’d go there early to get into the darkroom before anyone else.”

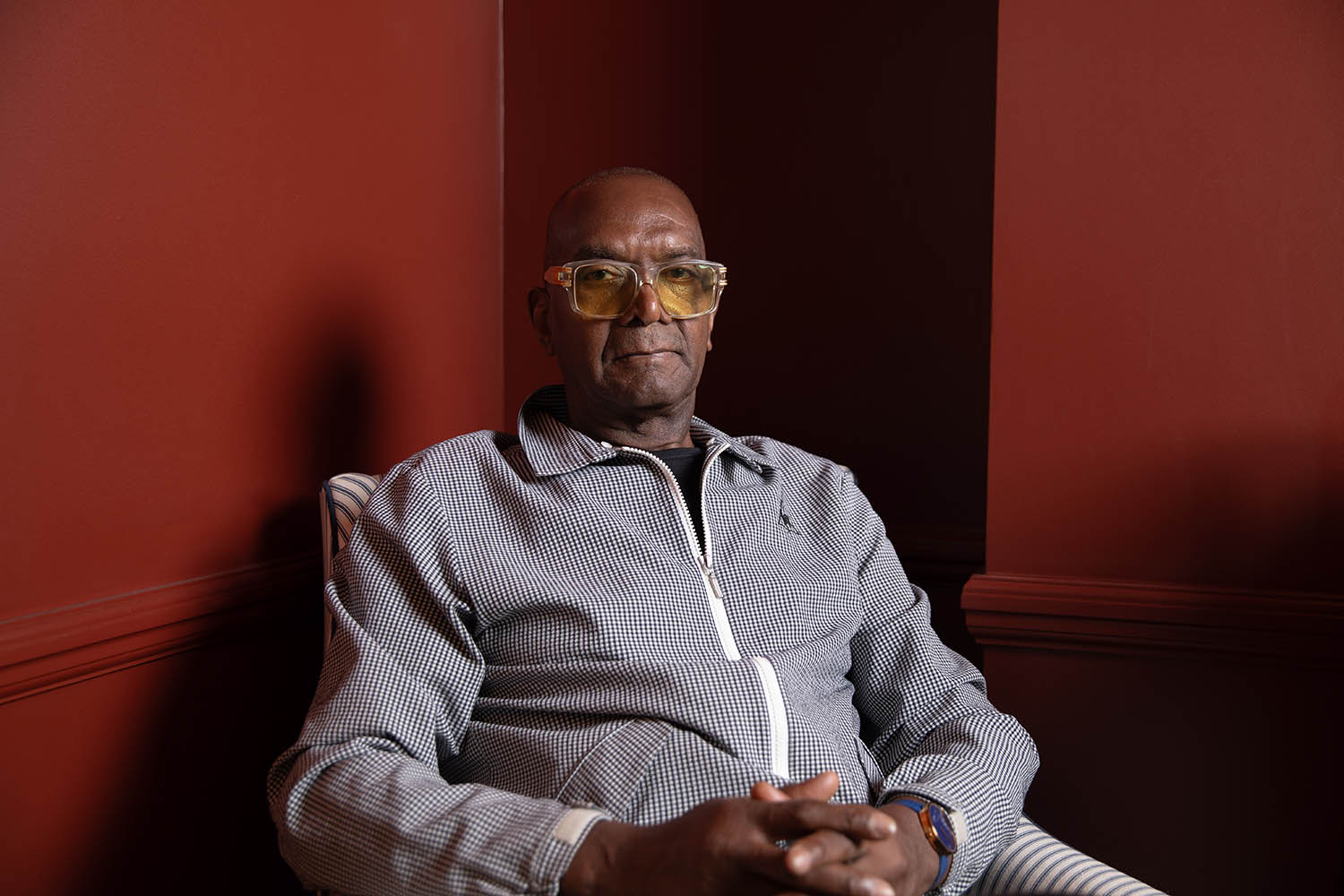

Dennis Morris photographed in London for the Observer

Aged 16, he was told by the school careers adviser that his ambition to pursue a career in photography was unrealistic. “What was actually said was, ‘There’s no such thing as a Black photographer.’” Morris says. “But I knew about Gordon Parks just as I knew about Cartier-Bresson.”

Soon afterwards, in 1973, he bunked off school and headed for central London intent on photographing a young reggae group called the Wailers, who were signed to Island Records and were about to play four nights at the Speakeasy Club as part of a UK tour. When the band members, dreadlocked and denim-clad, strolled down a side street towards the stage door to do a soundcheck, Morris was waiting. He had been there since early morning. Perhaps sensing something of his own laser-focused ambition in the young photographer, the group’s lead singer, Bob Marley, invited him to join them on the tour bus for the remaining dates of the tour.

“I never imagined that I would be given that kind of access,” Morris tells me, “but I had initiative and drive and I think Bob sensed that. On the tour, he never treated me as a kid, and that gave me the confidence to create the pictures I wanted.”

‘With Bob, no posing was needed’: Marley in a sports shop

The striking images of the young Bob Marley that Morris captured over the next 10 days are among the highlights of a new retrospective of his work at the Photographers’ Gallery in London, which features his music photography alongside social documentary projects taken in east London and Southall.

Morris shot Marley onstage, but also relaxing between shows, the results amounting to an intimate portrait of the artist on the cusp of the crossover success that would soon follow. Two years later, in July 1975, Bob Marley and the Wailers played two legendary shows at the Lyceum theatre in London, which were also witnessed at close hand by Morris. One of his iconic images of the singer performing was used on the sleeve of the classic album, Live!, which was recorded at those two Lyceum shows.

Since Marley’s death in 1981, aged 36, Morris’s early portraits of the reggae star have inevitably attained a bittersweet resonance. As the singer’s myth attained messianic proportions in the late 1970s, his features would assume, as the writer Philip Norman memorably put it, “the solemn, stoical look of some Haitian martyr saint”, but here he is as yet untroubled by the pressures of global fame. Fresh-faced, youthful and relaxed, Marley is effortlessly at ease in the camera’s gaze as he converses with Morris from the front of the tour bus, smokes a spliff backstage, and scrutinises a football in a cramped sports shop.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

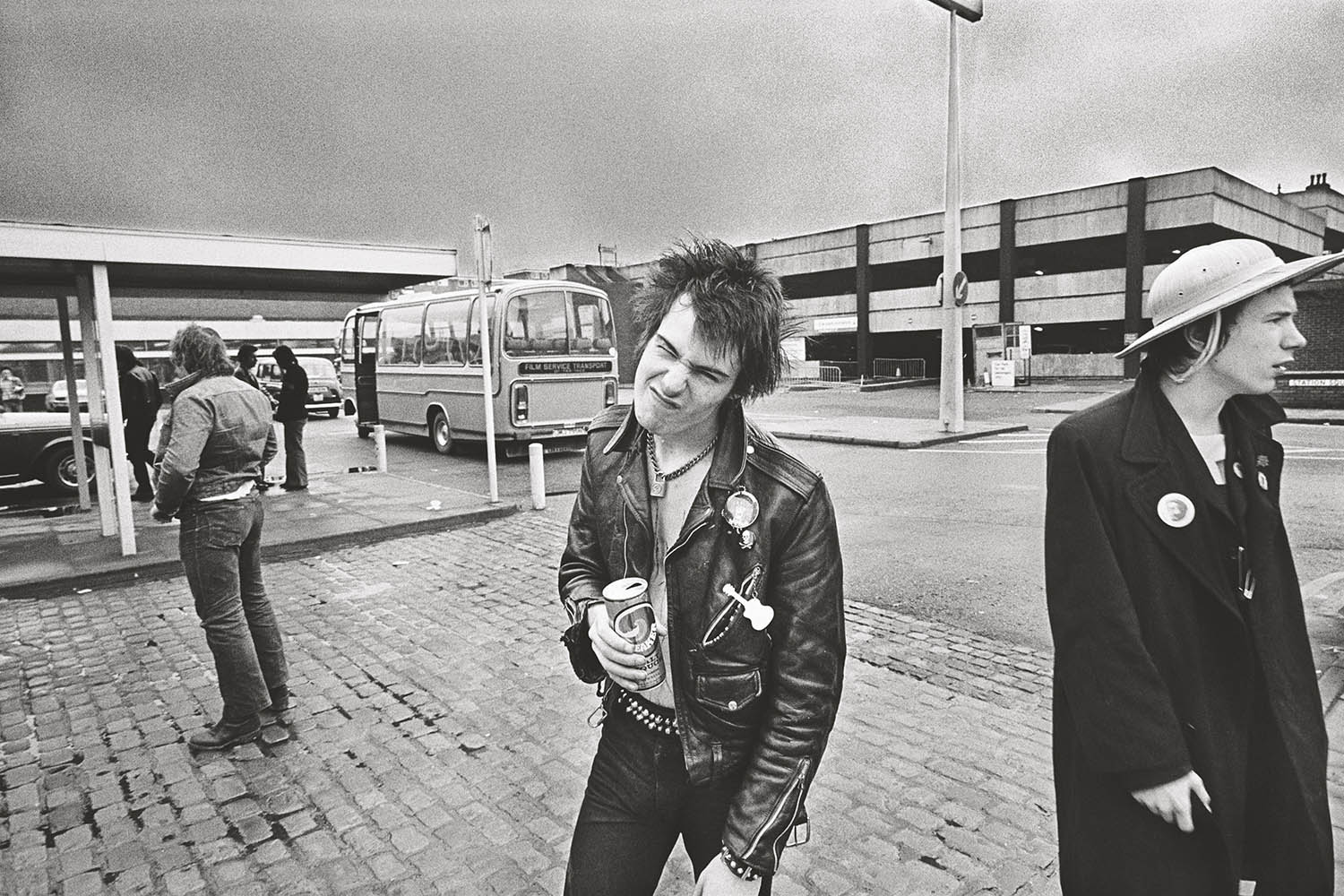

The Sex Pistols performing at the Marquee Club in London in May 1977

“With Bob, no posing was needed,” says Morris, “He had a presence that was more than star quality; it was spiritual. He was also incredibly focused. I watched him walk onstage in half-empty venues in towns like Leeds, where the Wailers were unknown save for a few pockets of West Indian people. No matter how small the audience, he would perform as if his life depended on it. His attitude was, ‘This is it!’ He wanted to reach people who would spread the word. From the off, his eye was on the bigger prize.”

From the beginning, Morris too was thinking outside the box, intent on producing projects rather than single images. His approach, which echoed his influences, set him apart from most other music photographers. Merging intimate documentary, reportage and portraiture, it depended above all on close collaboration with his subjects over an extended period of time, but also on being alert to the first tremors of the cultural shifts that would shape the 1970s and beyond.

The most seismic occurred in 1976, with the coming of the Sex Pistols and punk, a dissonant cultural rupture that reverberated beyond music, precipitating a feverish moral panic. Their debut album, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, and the incendiary anti-royalist single God Save the Queen were released to coincide with Elizabeth II’s silver jubilee celebrations in 1977. It was the height of the Sex Pistols’ notoriety and both records were banned by the BBC, along with the band’s earlier single Anarchy in the UK. The group were castigated by the tabloids and even assaulted in the street. Singer John Lydon (then known as Johnny Rotten) was stabbed outside a London pub in June 1977, and drummer Paul Cook was attacked by men wielding iron bars at Shepherd’s Bush tube station the following day.

Morris says that Sid Vicious’s persona ‘masked his shyness’

Having been summoned by the Sex Pistols’ maverick manager, Malcolm McLaren, Morris travelled with the group on a UK tour in August 1977. The band were billed as the Spots (Sex Pistols on Tour Secretly) in an effort to thwart local authorities intent on preventing them performing. Morris’s on-the-road reportage evokes the clamorous excitement of their performances, the camaraderie of a group under siege, and the chaos that trailed their self-destructive bassist, Sid Vicious.

In contrast to the spiritually charismatic aura of Bob Marley, the Pistols exuded a darker energy that emanated most forcefully from the dynamic between Vicious and Lydon. “I was closer to John,” says Morris. “We’d stay up late smoking weed and playing reggae tunes. There is one photo of Sid smoking, but he hated weed because it made him feel more alive. What he wanted was to just block everything out with smack. He was a damaged soul and there was a darkness there that was all too obvious.”

For all that, Morris found Vicious fascinating. “It seems odd to say it, but, underneath it all, Sid was shy. His persona masked that shyness. About 90% of the time he was out of it, but still able to communicate somehow. Sometimes he’d nod off and you had to give him a shove to wake him up when it was time to go. He didn’t really have to play the bass; he just looked so good on stage.” He pauses. “For me, the issue with Sid was that he never knew his own worth, whereas John understood that this was his moment.”

Sid never knew his worth but John understood that this was his moment

Sid never knew his worth but John understood that this was his moment

The intensity of the band’s performances is palpable. In one image, Lydon seems to be dissociating having just come offstage, his eyes rolling back in his head and his hands clasped over his crotch. Elsewhere, there are graphic glimpses of Vicious’s nihilist outlook. In one shot, his bass guitar is slung low over his pale torso, which is crisscrossed with self-inflicted slash marks. In another, his hotel room looks like it has been hit by a hurricane. The most darkly prescient is a fly-on-the-wall portrait of him, sprawled, face down and comatose, on a patterned carpet. He died soon after, in New York in February 1979, from a heroin overdose. He had been released from police custody on bail, having been charged with the fatal stabbing of his former girlfriend, Nancy Spungen. Like McLaren, who died in 2010, Morris is adamant that Vicious was not her killer. “He just didn’t have it in him to do that, no matter how out of it he was.”

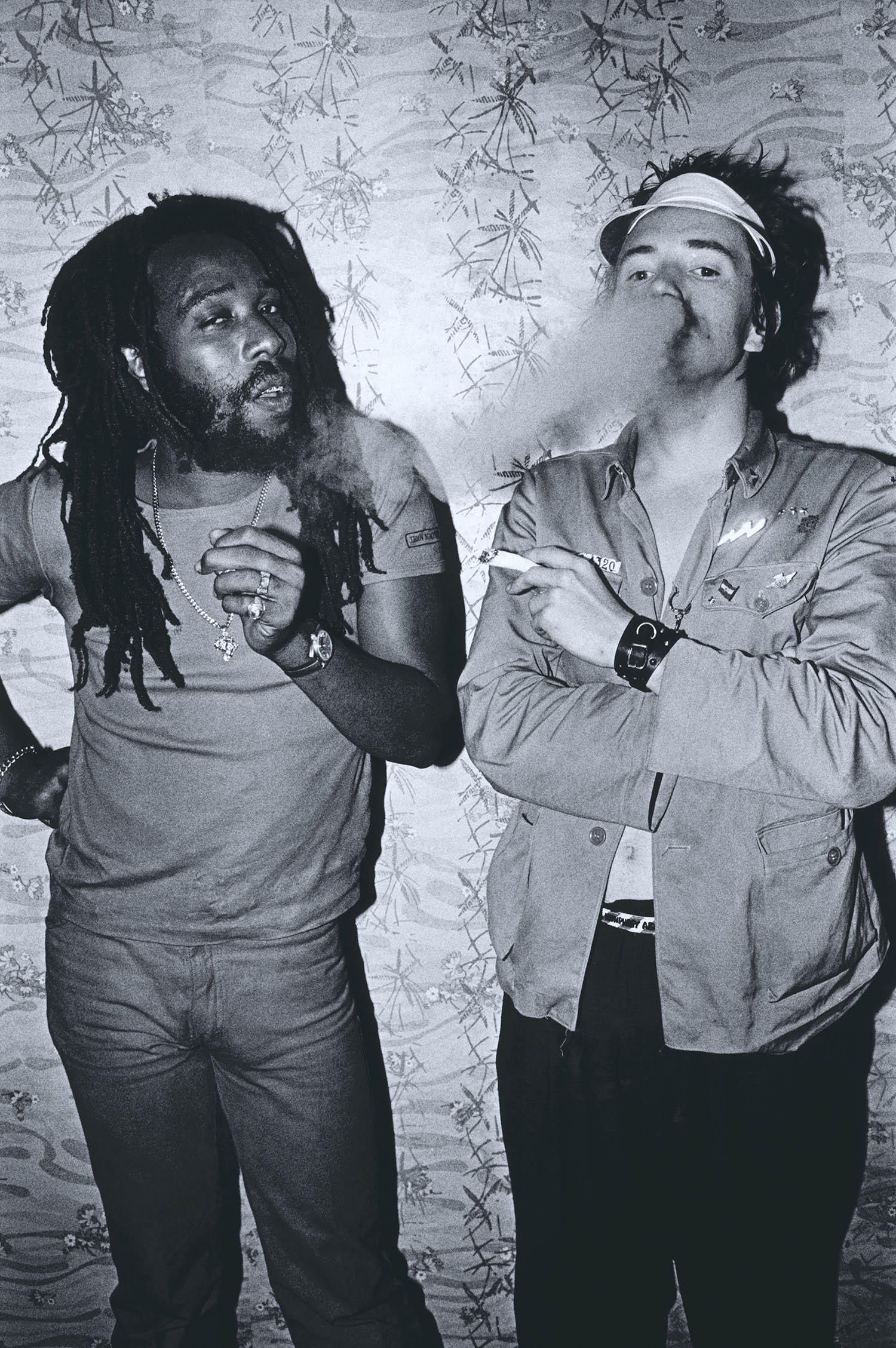

Johnny and Big Youth smoking, 1978

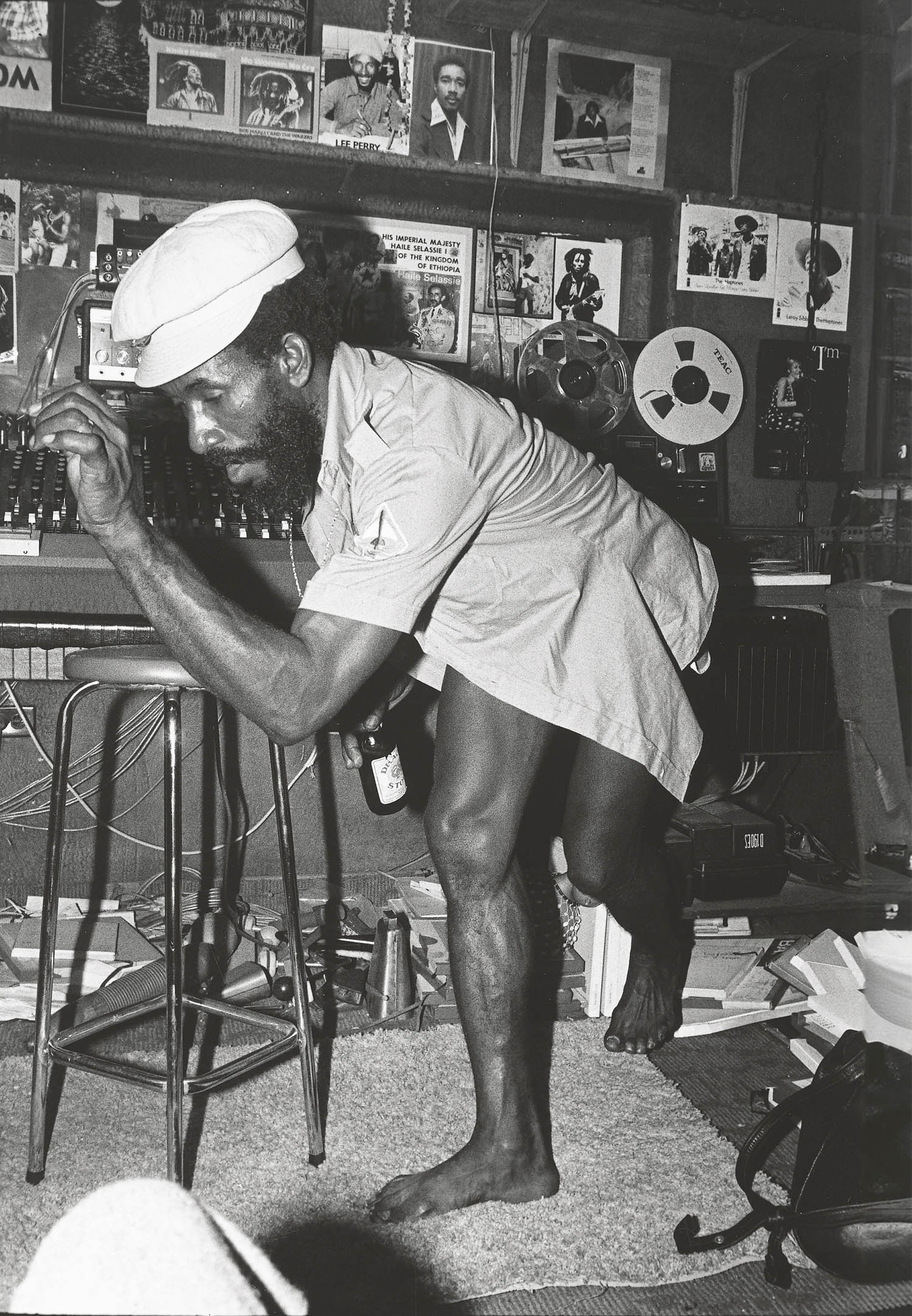

Morris continued his close collaboration with Lydon, travelling to Jamaica with him and Virgin Records boss Richard Branson to scout local talent for the latter’s fledgling reggae label, Front Line. Morris’s portraits of the island’s reggae musicians, including Burning Spear, Lee “Scratch” Perry and the Gladiators, are another highlight of the retrospective. In one photo, Lydon, spliff smoke billowing from his nostrils, stands alongside the legendary reggae DJ Big Youth.

“The Rastas loved John,” says Morris. “Just after we stepped off the plane in Kingston, a group of dreadlocks saw him and started shouting, ‘Johnny Rotten, man! God Save the Queen!’ They saw something in him that chimed with them, but I’m not sure what they’d think of him now.”

Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry in Jamaica in 1976

Morris has not crossed paths with the punk turned Maga supporter in years, and does not seem that keen to do so. He met Marley several times following that first teenage encounter that changed the course of his life. “Fame changed everyone around Bob, but not him,” he says. “He was essentially the same person with the same presence, at least until the shooting incident in Jamaica, which really shook him up.” In December 1976, two days before he performed at a concert that sought to unify Jamaica’s warring political factions, several armed men broke into Marley’s home on Hope Road. He was shot in the arm; his manager and his wife, Rita, were also shot during the attack. All three survived.

“Bob came to London soon after and he was a different person,” says Morris, quietly. “He wasn’t in hiding as such, but he felt safer in London. When we spoke, it was clear that he was shocked and disappointed that his people would do that to him. He was never on any side, so he just didn’t expect it.”

Photographs accrue meaning over time; the once contemporary becomes historical. For any young music fan coming to Morris’s work for the first time, several of the images cited above must seem revelatory. He once described his younger self as being “at the forefront of a new black British generation who had a double identity, a double culture”.

That cultural duality is most apparent in the two series that established his name as one of the very few black music photographers working in the 1970s. “I was never consciously chasing the next big thing,” he says. “I just sensed when there was something happening and followed my instincts. Then, I really dug down into it. I wanted to go deep, because I knew in time to come, it would be important.”

Dennis Morris: Music + Life is on at the Photographers’ Gallery in London until 28 September

Photographs by Dennis Morris, Anselm Ebulue