Seamus Murphy was first invited to work in Nablus on the West Bank in 2004, taking publicity pictures for the first Oscar-nominated Palestinian film, Paradise Now. The film, directed by Hany Abu Assad, was the fictional story of two Palestinian men who were planning a suicide bombing in Israel; its backdrop was the permanent refugee camps of Nablus.

The film-makers wanted the context of the second intifada against Israeli jurisdiction to seep into the atmosphere of their film. As well as documenting the film-making, Murphy’s role was to capture some of the real-life stories that were happening off camera.

The shoot went on for months; some of the German contingent of the crew quit when the location manager was kidnapped. In the three weeks before a French crew arrived to replace them, Murphy, a seasoned photographer of conflicts around the world, wandered Nablus following the sound of explosions, talking to people, looking for stories.

He returned to those camps and streets last month, 21 years later, in search of some of the people who had told him those stories. Murphy has worked in Gaza in the intervening years – he won a World Press Award as the first photographer to prove the existence of Hamas’s underground network of tunnels, until then widely thought to be Israeli propaganda – but not in the West Bank. It was, he suggests, both a sobering and elevating experience to go back.

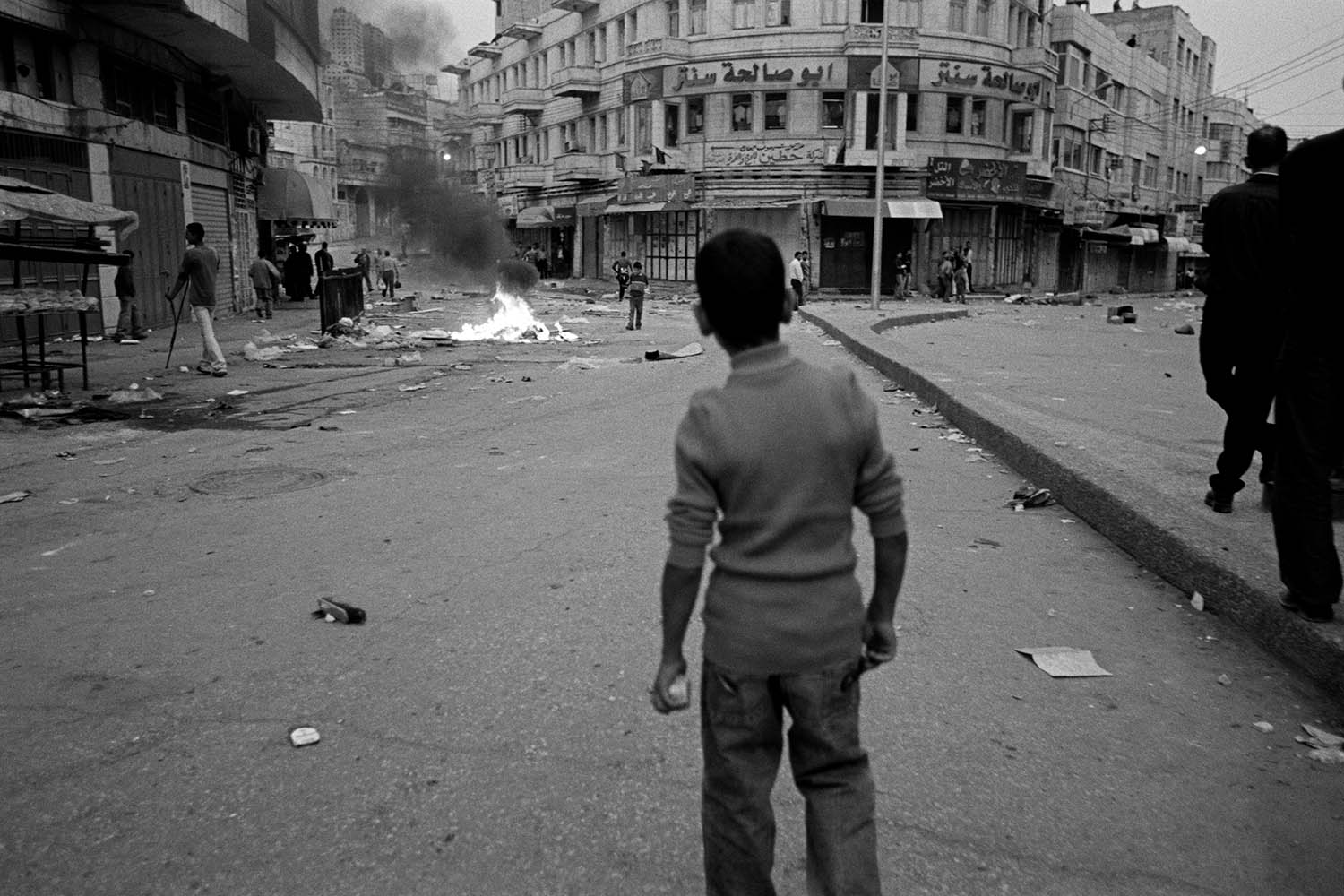

A clash in the second intifada of 2000 to 2005, which was the backdrop to the film Paradise Now …

… and the street this year

“I was reminded first what a spectacular city it is,” he told me this week. “It’s like San Francisco surrounded by hills. If you are up on the hill where the Samaritans live, you hear the call to prayer echoing across the valleys, it’s kind of magical.”

The situation he encountered in the streets was more despairing. He carried with him PDFs of his original pictures in the hope of finding people he had photographed two decades ago.

The task wasn’t easy. Though many people remembered the film-makers being there, many of his subjects were elusive.

“A lot had obviously died or been killed,” he says, “or you’d identify a stone-thrower and he wouldn’t want to be photographed because he had become respectable, a member of the Palestinian Authority.”

Eventually though, over the course of many days, he pieced together through portraits some of the story of those two decades.

“Compared with before, everyone there is so terrified of the Israel Defense Forces now,” he says. The war in Gaza, and now in Iran, has meant events in the West Bank go largely unreported.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

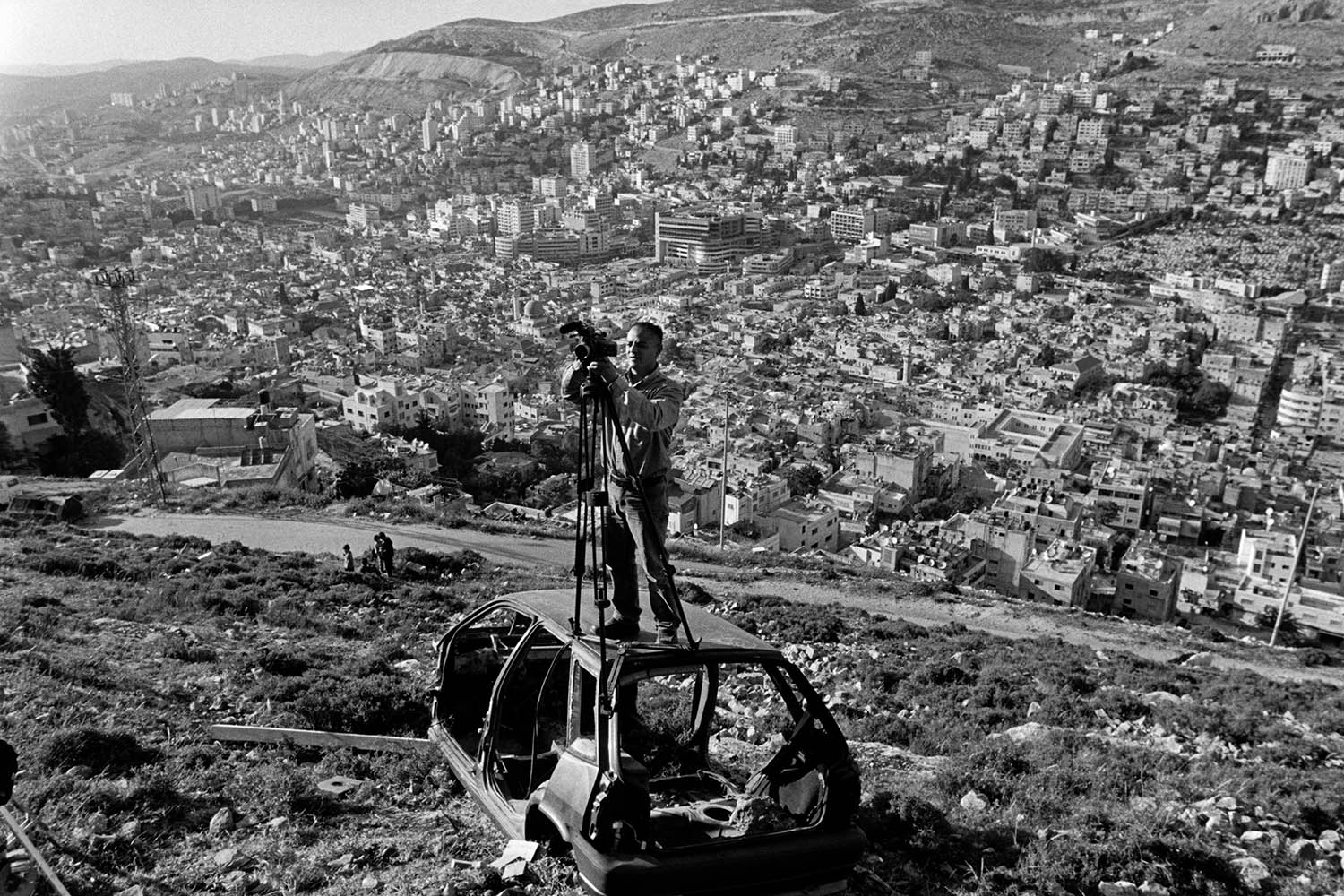

Rajae Al-Khateeb shoots footage of the making of the film Paradise Now on Gerizim Mountain …

… which is still home to a community of Samaritans

“A couple of days before I left,” he says, “I was woken by a house up the street being exploded by the IDF; it was punishment for the family of a guy who had planned a suicide bombing a couple of years earlier.”

The big difference in the refugee camps, he says, was that you didn’t see young Palestinians walking around with guns as you did before.

“There is less obvious resistance,” he says. “It’s as if they’ve tried violent resistance. They’ve tried non-violent resistance. Nothing works, and they’re now in a state of weary fatigue and hopelessness.”

When some of the people he spoke to looked at his photographs from 2004, when their city was on fire, it was with a kind of absurd nostalgia. He says: “There was this feeling, back then, that when we were attacked, at least somebody would do something, even if it was kids throwing stones. That’s not there any more. It’s like: those were the days.”

Basil Khalil Ibrahim Abu Lail, Balata camp

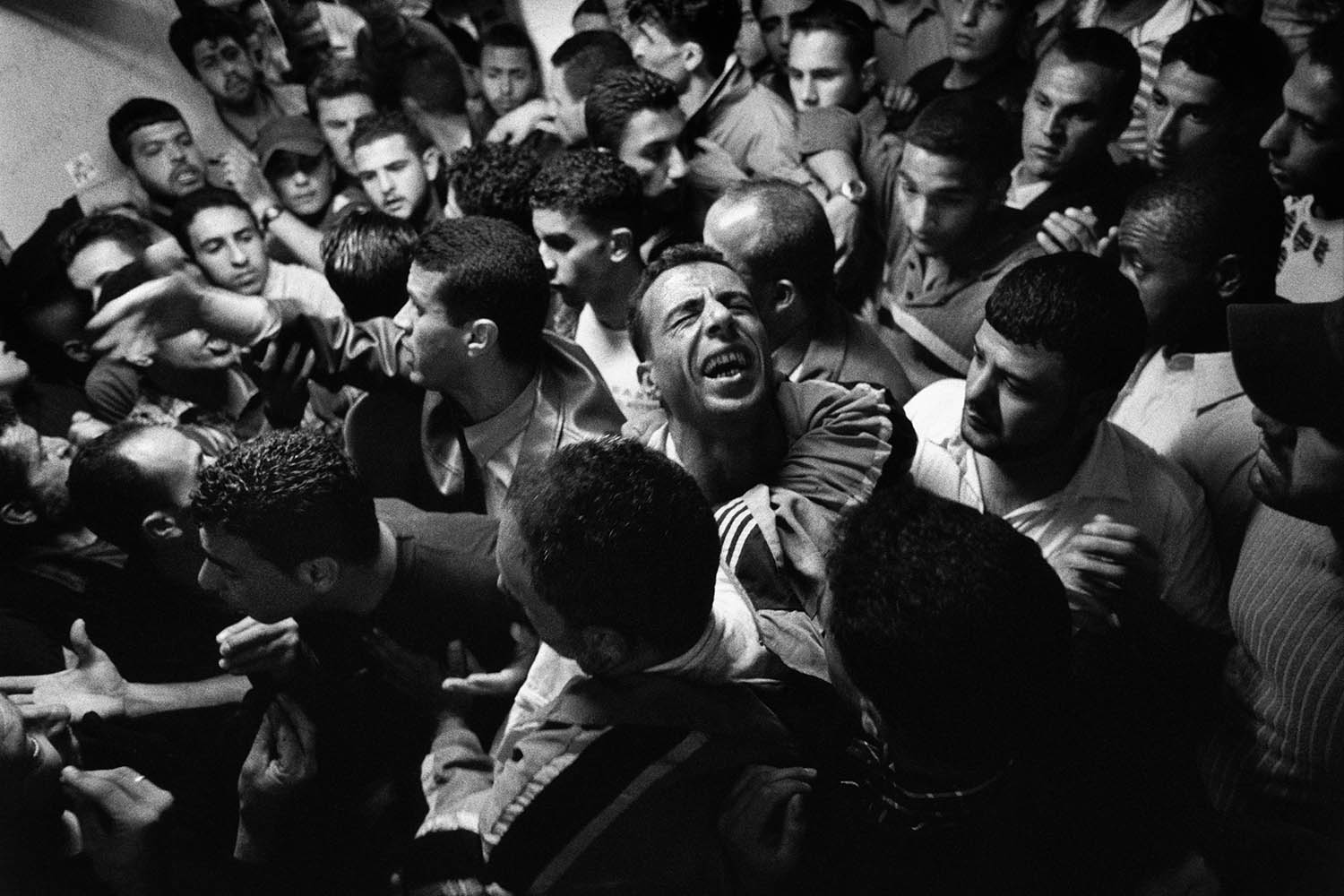

The picture from 2004 shows Basil after he discovered his best friend, Nader, had been killed. Basil was a taxi driver and Nader, who was on the Israeli security forces’ most-wanted lists as a commander of the Al-Aqsa brigades, called him from the nearby Al Ain camp for a lift. Basil’s taxi was being used by another driver, he recalls.

Minutes later he heard on the radio that Israeli forces had bombed a car next to Al Watani hospital in Nablus and four men had died. Basil guessed one would be Nader. Seamus Murphy photographed him at the hospital morgue (above) where his suspicions were confirmed. If Basil had given Nader the lift, Basil would have died too.

Speaking to Murphy last month, he said: “Nader and I did everything together, he was more like a brother than a friend.” Basil named his son after his friend; his wife was pregnant when Nader died. “It is so much harder now than in 2004. If you went to jail then someone could help your family,” Basil says. “Palestinians say prison is like a flower, everyone has to smell it.”

Um Ahmed Khdaesh, Balata camp

The picture at the top shows Um Ahmed Khdaesh during the intifada of 2004, which was the backdrop for the film Paradise Now. She is not sure of her age, though she believes she was forced to leave her home village near Haifa, now on Israel’s Mediterranean coast, when she was nine. That was during the 1948 Palestinian exodus from Israel, the Nakba. Her family were scattered, she recalls, some to Jenin on the West Bank, some to Beirut or Syria.

At 17 she married a man from her village. “We had our children and lived in tents at first,” she told Murphy, “then UNRWA gave us rooms. Later we built a home and eventually we moved here to Balata.” The Balata camp was built for 5,000 refugees; it now houses more than 33,000. “We were young,” she says, “now we are old.” She says she still remembers her former village: “We used to raise chickens, we ate tomatoes, olive oil, we gathered salt from the sea.”

Since the first picture, her son has been imprisoned, and when he was released as part of an exchange deal he was deported to Egypt. Um Ahmed dreams of dying back in Haifa.

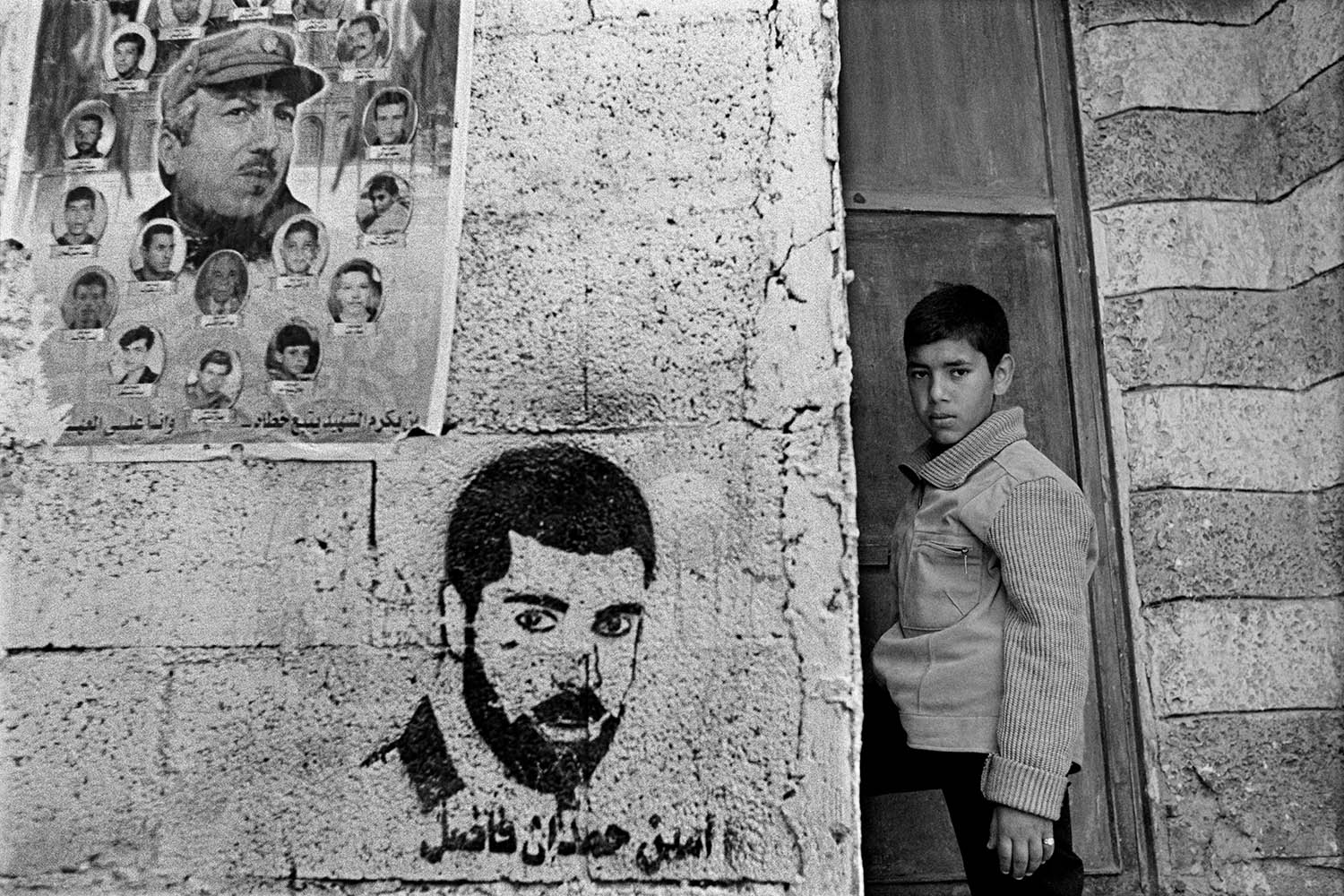

Mahmoud Bohi, Al Ain Camp

Mahmoud was only 10 when Paradise Now was filmed at his camp. He recalls “lots of people around, big lights being carried, a lot of activity”. Seamus Murphy’s first portrait of him (top) was taken across the street from his house, during the making of the film.

Two years ago, Mahmoud was shot in the head by a sniper. His mother recalls how her son was at home and went outside with his phone and cigarettes, and a few minutes later people were shouting that he had been shot and killed. He says he had reached for his phone to film Israeli soldiers in the camp to post on the Telegram platform (a common activity that allows Palestinians to know what is going on, and which places to avoid). He did not die. He was instead in a coma for eight months.

He has been for surgery six times, most recently on his skull, where he has a large bullet hole. Mahmoud’s brother Ahmad Bohi, who had been imprisoned and was released as part of a prisoner exchange programme insisted to Murphy that his brother had nothing to do with the resistance. He said: “His only crime was being Palestinian.”

An exhibition of Seamus Murphy’s Nablus pictures, Smoke and Mirrors, is at the Bradford literature festival from 26 June to 6 July

Additional reporting by Tim Adams