I think of him as “the bear”, up to his eyes in fur against the freezing snow, so far north he could be on a polar expedition. All you can see of this man, in the breathing gap between upturned collar and hat, are two glinting eyes and a fraction of nose. His hands are invisible, muffed inside heavy coat sleeves against the icy air swirling around him. Snow falls, settling in white heaps on his fur hat and shoulders.

But Alexander Buxton is nowhere near the north pole – in fact he is not even outdoors. This photograph was taken in a studio in downtown Montreal in the 1880s, without the aid of a wind machine, let alone actual snow.

Buxton arrives punctually for his appointment (meticulous studio records survive, giving the hour of midday) bringing along the copious furs he liked to wear on wintry Canadian hikes. He is to pose for the celebrated photographer William Notman. They take several shots, but this is by far the best: tilting at a very slight angle, as if withstanding Arctic blasts. And then the session is over.

How did the snow get into the picture? Notman was always exceptionally candid about his methods. On the fur coat, he scattered a little rock salt; on the negative something quite else. “Get some Chinese white,” he told a Montreal reporter in the 1860s, “and introduce it into one of those ingenious contrivances for blowing perfume – to be had at any drugstore. Blow a shower of the liquid paint into the air and, while it falls, catch as much as desirable on the varnished side of the negative.”

Notman might be the most experimental of all 19th-century photographers. He doesn’t just master the very latest innovations. As early as the 1850s, one of his studio advertisements offers everything from the daguerreotype to the stereoscopic street scene – two images juxtaposed to give the illusion of three-dimensional depth – and from the tiniest miniature portrait for the locket to the life-size headshot. Beyond even this variety, Notman invents whole new ways of making images, and for the most unusual of reasons.

Canada is young in the mid-century, expanding all the time as railways are beginning to be built across unthinkable distances from one coast to the other. More and more migrants are arriving: to make their way, and hopefully their fortune, to build a new and independent nation. The landscape is vast, spectacular, snow-capped.

Members of the Montreal Snow Shoe Club fling a fellow rambler skywards in The Bounce

The new winter sports – sledging, curling, hockey, even a kind of Victorian dancing on ice – can’t easily be photographed on the spot, in freezing conditions, because there are too many people involved.

Notman wants to show the nation growing right before its own eyes, and so his photography expands ingeniously. He was a migrant himself, born in Paisley in 1826.

I first came across him searching for the earliest photographs of my home country in the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh, among Hill and Adamson’s favourite fishwives, and Henry Fox Talbot’s fading “sun pictures” of the Scott Monument being erected on Princes Street. Unlike mine, Notman’s Scottish accent never waned. The family moved when Notman was 14 to Grafton Street in Glasgow, where he took a teenage interest in the split-new invention of photography. He studied drawing and painting, but was required to join his father in the woollen goods business, until a financial crisis sent him off to Montreal in 1856 to find work in a dry goods store. There he rented a house on downtown Bleury Street and opened his first small studio in the back.

Within four years, he is winning prizes, inaugurating the Art Association of Montreal, expanding into the next-door house and establishing an art department for the painting of backgrounds and the creation of studio decor. Notman would become the most successful photographer in the history of the country.

For a time, all of Canada was his subject. He took photographs of men working at the farthest end of the tracks as the new rails were gradually laid across the prairies to the Pacific, of First Nation Indigenous people on horseback (and in triumphant lacrosse teams), of French and Chinese road builders constructing perilous routes through the Rockies. Calgary, in 1860, has barely 100 houses in his haunting photograph; now its population is on its way to two million. Commissioned to document the new Victoria Bridge, over the wide St Lawrence River, Montreal’s Thames, Notman photographed the struts from below, rising in abstract forms against the sky, and then showed the view from right up on the spars above the water to give a sense of its colossal span and scale.

Most of these images were made using the collodion method: a glass plate, coated with an iodised solution, becomes light sensitive when dipped in a tray of silver nitrate. The process is known as wet plate because the photographer has to coat, expose and develop the plate all before it dries in about 15 minutes. The process only thrived for about 25 years before the dry plate method was developed, whereupon all the cumbersome apparatus required to achieve it was suddenly redundant.

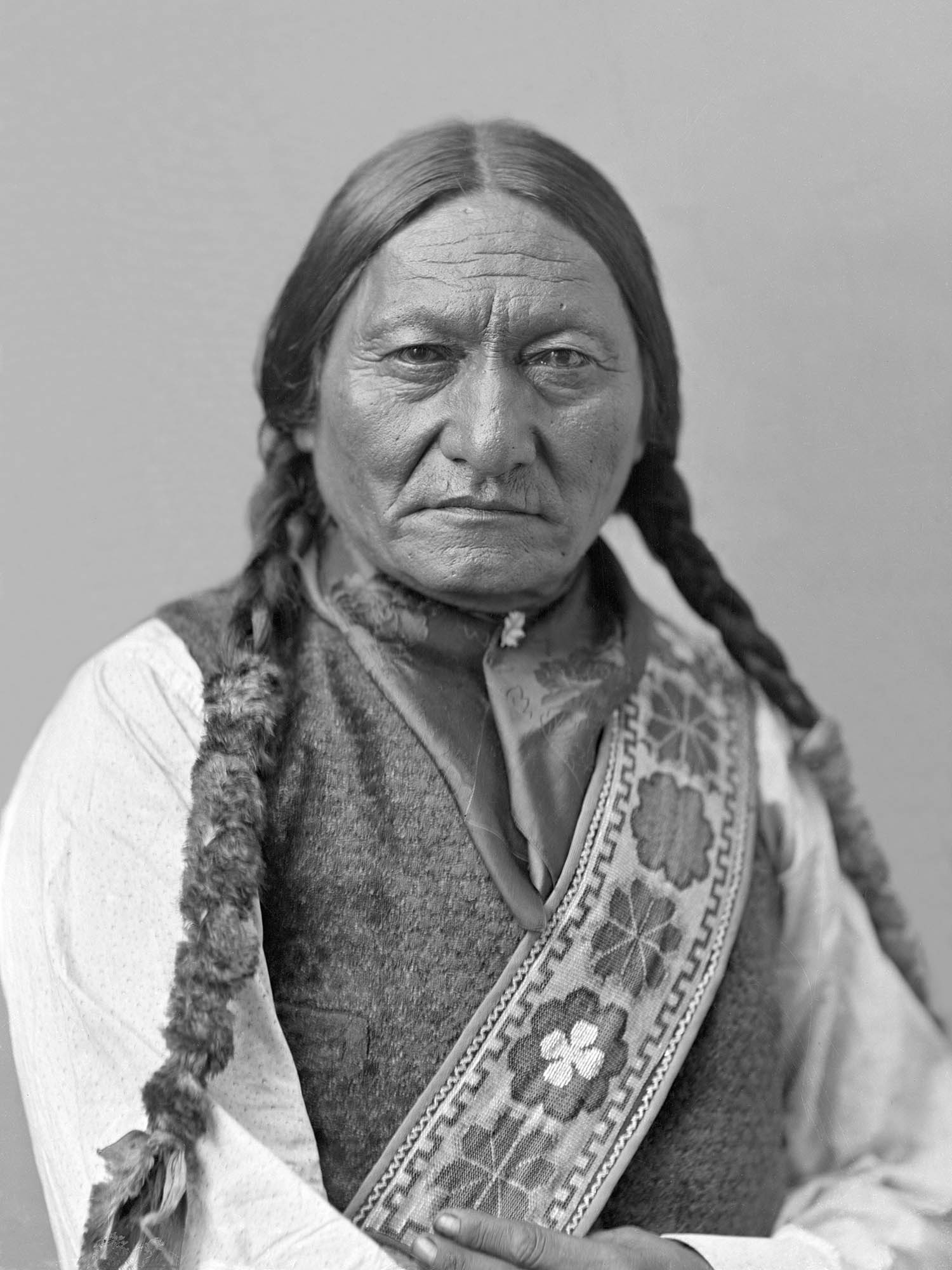

‘A countenance seamed and wrinkled’: Notman’s portrait of Sitting Bull

Out in the wilds, photographing logging, fishing or the trapping of bears, Notman somehow had to erect a darkroom for all this coating and developing – no mean feat in heavy snows. Just to lug the equipment across the terrain was a labour in itself. In Montreal, he had a portable darkroom that could be moved by cart in summer and sledge in winter. But very soon, Notman found a way of bringing the outside indoors.

There is a campfire scene from 1866, where five moose hunters are huddling round a fire by night. An eerie Blair Witch wood spreads into the shadows around them. Notman had a brown carpet in his studio that was so shabby, he said, that any amount of grass, straw and wood could be strewn across it to create a landscape without ruining the pile. The glowing fire, its exact source concealed within the ring of figures, is in fact a magnesium flare.

In another shot, the Grindley family are shooting down a slope on a toboggan. Except that the scene is carefully posed in the studio, where the toboggan is balanced at an angle against a white sheet. The snow is added later – Notman often used white fox fur, as well as rock salt, and hired an artist to paint the distant winter backdrop. Then he cut all the different elements together and photographed them again on a single plate. Call it Photoshop.

Notman was already such a gifted portrait photographer that for a celebrity to visit Montreal without passing through Notman’s studio was virtually unthinkable, quite apart from the citizens themselves. Matrons in rustling crinolines; boys in stiff gaiters; Alice in Wonderland girls. Customers could have a dignified cabinet photograph – preferred by politicians and prelates – or something more nuanced.

He was always psychologically astute. He photographed Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John Macdonald, a fellow Scot, looking like a Victorian actor – smiling, legs raffishly crossed, in a natty checked waistcoat and trousers. Buffalo Bill looks exactly as contemporaries said he looked: all waxed moustachios, a stage musketeer.

Most affecting is Sitting Bull, in all his melancholy beauty, one eye clouded with a cataract. Notman’s portrait exactly equates with the description of a Montreal report: “A countenance seamed and wrinkled, as becomes a chief upon whose head war and wrong have beaten for half a century.”

All are passing through an ever-expanding studio that was itself pictured in a lithograph of 1872. In a lavish reception area, customers are viewing and choosing formats, queuing and paying; through a doorway, a society hostess is getting ready for her closeup. Paintings line the walls – photography is also an art – alongside photographs in every size. Anyone booking an appointment would receive an advance copy of Notman’s pamphlet Photography: Things You Ought to Know, which, in addition to begging customers to leave their glum faces at home, proposed they give themselves up to the photographer’s judgment, experience and aesthetic eye.

The Grindley family on a toboggan. The snow was made up of white fox fur and rock salt, and the background was painted

Photography was still so new – its market embryonic when Notman first arrived in Canada – that sitters sometimes had no real idea what to expect. And what he gave could be fantastically theatrical.

Three little boys are pictured fishing off a bridge in a wood; a pond was specially created in the studio. Miss Evans holds a tea party, and pours the invisible drink into cups for her guests in a lavish parlour. One girl whispers the latest gossip to another while a couple of sultry beauties arrange themselves in a summer hammock.

“Gent for Mrs Austen” is all that appears in the studio records, alluding to a sequence of photographs of a man dressed as a woman, hands judiciously folded and feet foreshortened, to conceal their size, on a cushioned chair. It is 1889, and Kodak has recently invented a small portable camera, but still this gent comes to Notman’s studio for this elaborate cross-dressing session. Miss Evans’s teapot, incidentally, reappears in these pictures.

There are premonitions in Notman of Annie Leibowitz’s lavishly staged productions the following century, featuring everyone from actors and singers to monarchs. But there is also something of the great German photographer August Sander in Notman’s much earlier ambition to photograph a whole nation.

A beautifully austere image of a plasterer shows him all in white, aptly, holding his plastering tray and bowl perfectly still (or not quite – there is a faint tremor of movement). His hand is dusted pale as the plaster. The room is bare: you can just see the slight curl where the white canvas backdrop meets the floor. The photographer gives every respect to the craftsman.

Notman ran all the way from the daguerreotype to the instantaneous photograph – capturing a blur of movement in a momentary exposure – in his first Canadian year alone. He even went further than the quick-change photographers who managed to get passing pedestrians on to their glass plates and then develop them in minutes in the back of a carriage. To photograph the torrential motion of Niagara Falls in 1859, he took two stereographic photographs of the same scene. One, underexposed, showed the clouds to motionless perfection. The other, overexposed, shows the hurtling water but not the clouds. He superimposed the two on one plate – ever-inventive – and printed The Falls.

A photograph from the series known as ‘Gent for Mrs Austen’

Notman created popular photographic books. In 1869, his portrait of Prince Arthur, son of Queen Victoria, on a royal tour of Canada became the first halftone photographic reproduction ever to appear in a newspaper.

He opened studios in Halifax and Toronto, Ottawa, New York and Boston, with special sets where Harvard graduates could be photographed with their scrolls. In 1876 he invented a photographic ticket for exhibitors at the Centennial international exhibition in Philadelphia – a prototype of the photo ID card. Despite this staggering speed of innovation, outside Canada he is still barely known.

Zestful, dynamic, ever-curious, Notman’s self-portraits show him – always with the Victorian beard fringing his otherwise bare face, in increasingly well-tailored wool or fur – surrounded by urgent letters and the very latest photographic periodicals. And the supreme stage direction of his photographs is achieved through the most progressive collage and edit. His great invention is the composite, where all the different elements – figures, props, painted backdrops, painted negatives – are united in one collage, and then rephotographed to make the great image.

Now far-flung families could all be in the same room, or at the same wedding. The members of the bicycle club – 50 medalled pedalists – can appear on wheels in the same landscape. Sledge champions can shoot down a hill, laughing and tumbling sideways. Notman even managed to cram more than 200 Canadians into a famous ice ball in 1870 – and they all came to be photographed separately, in their expressive poses, at his studio.

Exposure times were not yet fast enough for outdoor action shots, and who had a studio large enough, or equipped with enough posing stands, for so many people, in any case? Notman’s brilliance is in getting everyone in. His individual portraits are so intelligent and acute, but put together in these compositions, they give a full sense of this ever-growing nation in all its dynamic and sociable scale.

And for me, at least, the image that most epitomises the ebullience of both Canada and Notman himself, is The Bounce from 1886. The scene is late afternoon, solid snow. Eight members of the famous Montreal Snow Shoe Club, who tramped a dozen miles every Saturday, dressed in their jauntily striped club coats, are all grinning upwards at a ninth.

They have flung him in the air, where he appears to fly above them, arms spread, for sheer unbridled joy.

You can hear Speed of Light, written and read by Laura Cumming, at 11.45am from Mon day 28 July to Fri day 1 Aug ust on BBC Radio 4 and BBC Sounds

Photographs by William Notman