Krapp’s Last Tape

York Theatre Royal; until 17 May

Why would I rather see Krapp’s Last Tape than Waiting for Godot? Both plays are drenched in disappointment: Godot (1952) from defeated expectation, Krapp (1958) from the losses of the past. Yet Godot, which won Samuel Beckett the credit for wiring us into our own weird condition, now strikes me as too glaring and mechanical in its disruptive intent. Krapp holds the audience in a human conversation.

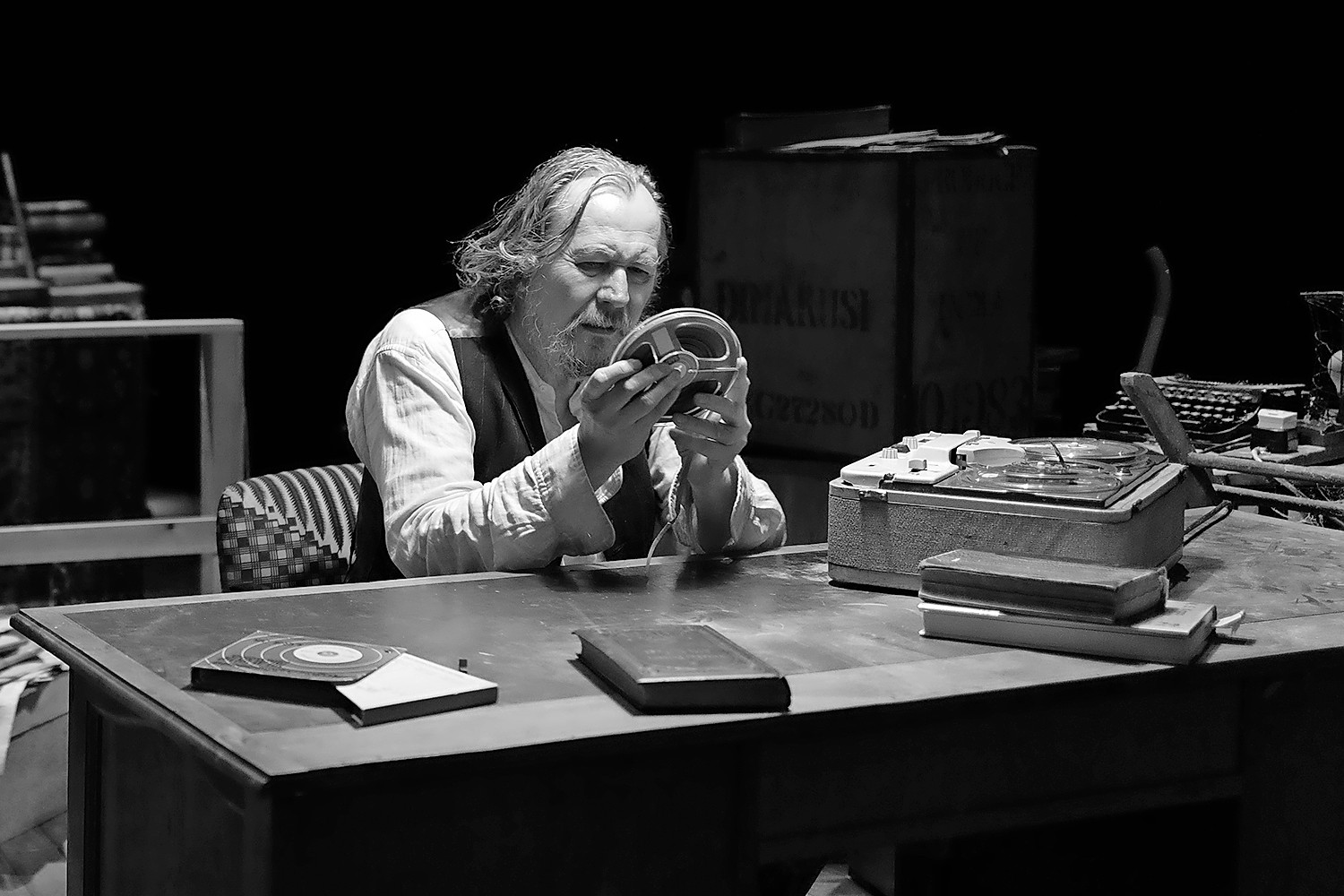

As Gary Oldman proves. Shambling but precise, in shirt sleeves, waistcoat and with raggle-taggle Slow Horses hair, he is the 69-year-old Krapp, playing back recordings he made 30 years earlier. Questioning his taped memories – of his dying mother, a girl in a punt, an old woman’s songs – he abruptly pauses them, creating parody cliffhangers from daily incidents.

In an extraordinary triple feat – crediting his producing partner, Douglas Urbanski – Oldman is also director and designer, creating a set that is a hoarder’s paradise: bottles and biscuit tins (for the tapes), heaps of upturned chairs and books, so closely piled that they look melded. As the sole performer, both natural and baroque, he reveals something essential: that this is not a character sketch – it is hard to say what Krapp is actually like – but a capture of moods and moments. Nor is it a confession. There is regret but not judgment. All is rage and reverie.

Krapp’s Last Tape has been acted by prisoners in San Quentin and made into a chamber opera. It goes to the wellspring of an actor. Well, most of the time: when Albert Finney played the part, Beckett went to sleep in rehearsals. In 2006, two years before he died, Harold Pinter was glorious in a wheelchair, full of gravel-voiced anger. In 2036, when he will be Krapp’s age, Samuel West will play him, drawing on recordings he made when he was 39. At the Barbican, Stephen Rea is about to reprise his acclaimed Dublin performance.

Closeup TV skills – a flicker across the face, a casually telling gesture – are evident

Closeup TV skills – a flicker across the face, a casually telling gesture – are evident

Oldman, with his gift of explosive containment – think of him as George Smiley, swimming with his specs on, in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy – is finely attuned to Krapp’s Last Tape, which needs a strong pulse and a sceptical eye. Beckett, who wrote the monologue to accompany the harsh Endgame, said it was like the “little heart of an artichoke served before the tripes with excrement”. He thought it had “a woman’s tone” – apparently a synonym for lyricism – and was pleased when the direction was “pitiless”. It is possible to imagine a warbling actor dipping into sentimentality. That doesn’t happen here.

Oldman brings an extra layer to this revolving of the past: he is himself returning, having made his professional acting debut at York Theatre Royal. Though he is now more familiar on screen than on stage, I still remember the impression he made 40 years ago at the Almeida, when he appeared opposite Peter Eyre in Francis Wyndham’s Abel and Cain: the author was transported.

Related articles:

Closeup television skills – a flicker across the face, a casually telling gesture – are evident: Oldman pats the tape recorder appeasingly, as if it were a dog. The sounds of the play are even more crucial. Audiences are primed to listen acutely by the opening sequence in which Krapp fools around with bananas (Beckett’s friends devised a dish called “Banane à la Krapp”) but says nothing. Words are stretched operatically – “spooool” – so that meaning dissolves. Krapp’s wheezes and splutters take their place alongside the click and rustle of the tape recorder as part of an intricate, intimate soundscape.

Beckett wrote Krapp for Patrick Magee, enchanted by the actor’s “ruined” voice and Irish rhythms, and referred to it as “the Magee monologue”. Crucially, Oldman successfully delivers two different voices: the taped younger version is not merely brisker but a different pitch from his older, creakier self.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

In the extraordinary notebooks he kept when directing Krapp in Berlin in 1969, Beckett specified to the second the length some actions should take. He suggested some of the play’s dynamics: the contrasts between light and darkness, the sudden shifts from stillness to movement. He was never keen to discuss autobiographical links, though many have been uncovered: not only the references to his mother and his early love affair with a cousin, but the glancing allusion to a lesbian novelist friend who specialised in fiction about dogs. Of course, he wanted his play to stand by itself. As it does. “What,” sighs Krapp, nostalgic for wretchedness, “remains of all that misery?” One of the most compelling hours in 20th-century theatre.

Photograph Gisele Schmidt