Titus Andronicus

Swan theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon; until 7 June

The prize for the most challenging Shakespearean stage direction is up for grabs. “Exit, pursued by a bear” has long been presumed the winner: the Royal Shakespeare Company has an enormous stuffed bruin looming near its Stratford bookstall. Yet equally jolting is the description of a messenger in Titus Andronicus. He comes on carrying “two heads and a hand”. They are a gift for Titus. The heads belonged to his sons.

Hugely popular when originally staged in 1594, Shakespeare’s first tragedy has been critically reviled – TS Eliot considered it “one of the stupidest and most uninspired plays ever written” – but intermittently acclaimed and rehabilitated, notably in 20th-century productions by Peter Brook and Deborah Warner.

It is still most famous for being Shakespeare’s goriest drama. Three of Titus’s sons are killed in the course of the action (21 others have already died on the battlefield). His daughter, Lavinia, is raped, has her hands cut off and her tongue gouged out. Titus chops off one of his own hands. Oh, and he bakes his enemy’s sons in a pie and feeds them to her. Beside all this, the blinding of Gloucester in King Lear pales: the “vile jelly” of his torn-out eye looks like an amuse-bouche.

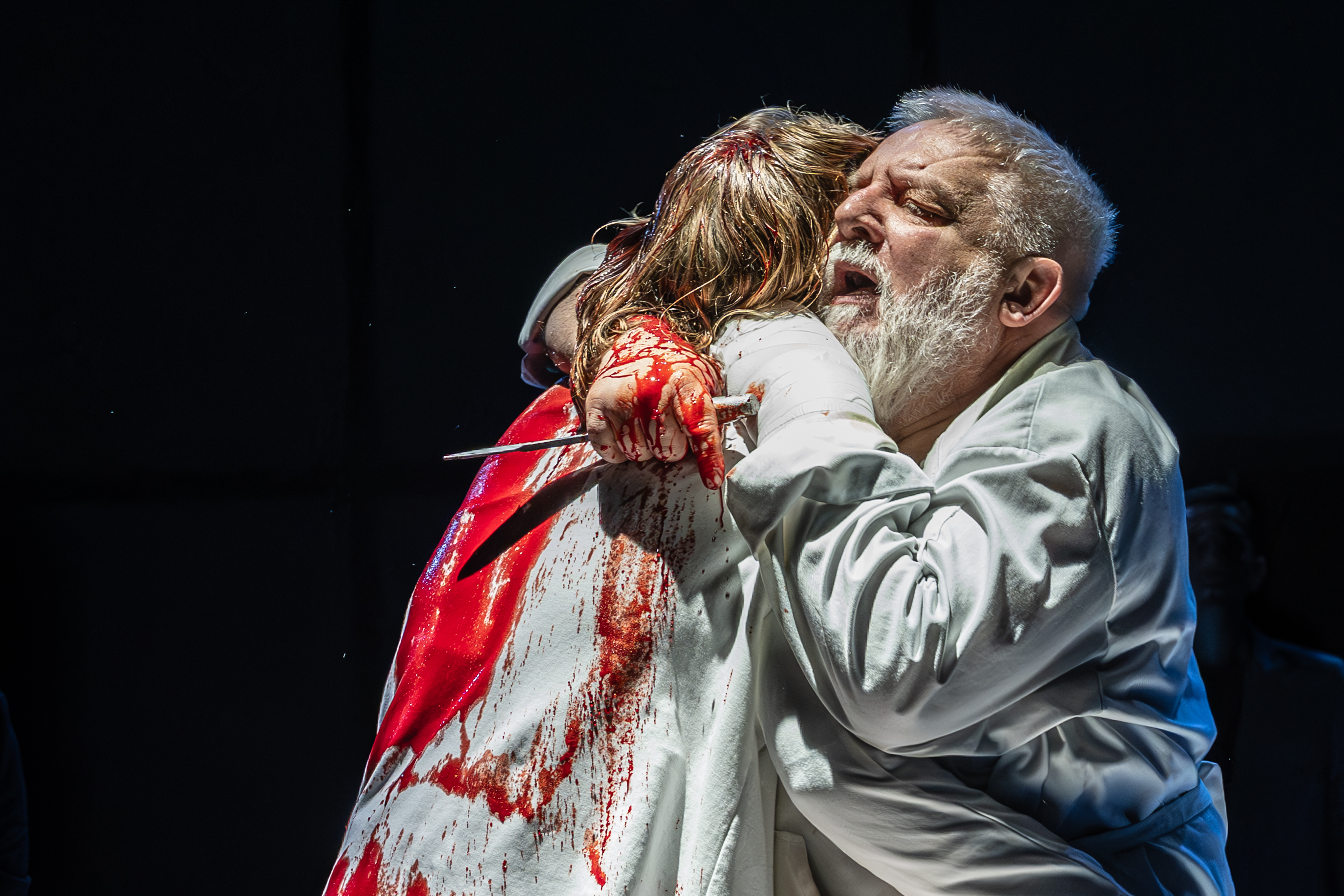

Max Webster’s authoritative production sears through difficulties. He is having an extraordinary directorial spell: a haunting Macbeth in 2023 with Cush Jumbo, David Tennant and headphones; a gorgeous, froufrou The Importance of Being Earnest (2024). Here he dispels the congestion of the opening scenes with their information about Roman-Goth warfare and the tussle between would-be emperors for the right to Rome. He steers the action with triumphant clarity: what can look slasher-slapdash becomes incisive, at once blood-spattered and austere.

Joanna Scotcher has restricted the palette of her design for both set – a translucent screen at the back; a huge hook dangling from the rafters – and costumes to black, blue, red, and silver. Everything and everyone is made immediately apparent. Lavinia collects the blood of her rapists in a scarlet washing-up bowl.

Defence of the play has often been theatrically academic. It echoes Hamlet in being driven by revenge, though, crucially, not by introspection. It recalls Othello in the shape of the villain Aaron, played with flair by Natey Jones: he is a Moor but is fuelled by Iago-like fury – the original angry young man. In the 1850s, the mighty African-American actor Ira Aldridge starred in an adaptation that granted the character nobility; he always has magnetism.

Beside all this, the ‘vile jelly’ of Gloucester’s torn-out eye looks like an amuse-bouche

Beside all this, the ‘vile jelly’ of Gloucester’s torn-out eye looks like an amuse-bouche

Yet time, television and Webster’s touch give Titus Andronicus greater resonance. After 21st-century atrocities have been so widely viewed, the extreme violence of the drama looks simply realistic. The depiction of the brutalities is candid: Evelyn Waugh scoffed at Brook’s production for “squeamishness” when Vivien Leigh’s mutilated Lavinia entered with not blood but ribbons streaming from her mouth and hands. What’s more, the puns and queasy jokes that accompany the lopping off of limbs now seem shockingly plausible: hysterical reactions, another ring of horror.

None of this would work without a company of strong speakers: Joshua James is a crisp incoming emperor, Emma Fielding marvellously supple as (gender-switched) Titus’s sister. Simon Russell Beale’s Titus is a titan. It is not only that he uses his easy command of the verse to amplify unsuspected beauties – “She is the weeping welkin, I the earth.” He does so without trying to turn Titus into Lear. He is a public figure, not given to self-examination, who booms and declaims, but who, confronted with terrible tragedy, melts his audience.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Russell Beale has described how, seeking a disturbing human aspect when playing Richard III, he pinched from Coronation Street, influenced by the celebrated moment when Jean Alexander as raucous Hilda Ogden opened the small bundle of goods returned by the hospital where her husband, Stan, had died – and broke down over his specs.

No specs here, but a similar shift of register as Titus moves towards his maimed daughter and, buttoned up in his dark overcoat, bends to stroke her hair. The general is a father. Russell Beale made me hear for the first time the intense pain and complete love in one exchange. “This was thy daughter,” he is told as the bleeding Lavinia enters. Titus answers simply: “Why... so she is.” No sentimentality either. Hear the glee with which Russell Beale, dressed in a pinny, announces his menu: a human-filled “pasty”. Sweeney Todd eat your heart out.

Photograph Marc Brenner