Halfway through this season of The Celebrity Traitors, Stephen Fry suggested something novel for a series that subsists on rumourmongering and sowing suspicion: he proposed they vote for who to banish without prior discussion. At the time, speculation surrounded Jonathan Ross after his most vocal accuser Ruth Codd was murdered. The question that lingered that day was whether it was so obvious a move by Ross that it was in fact a double bluff. But Fry, whose proudest contribution up until that point had been a roll call of the deaths in Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet during a mission, could recognise the fog of confusion that descended during discussions at the roundtable, and how it was causing them to fail.

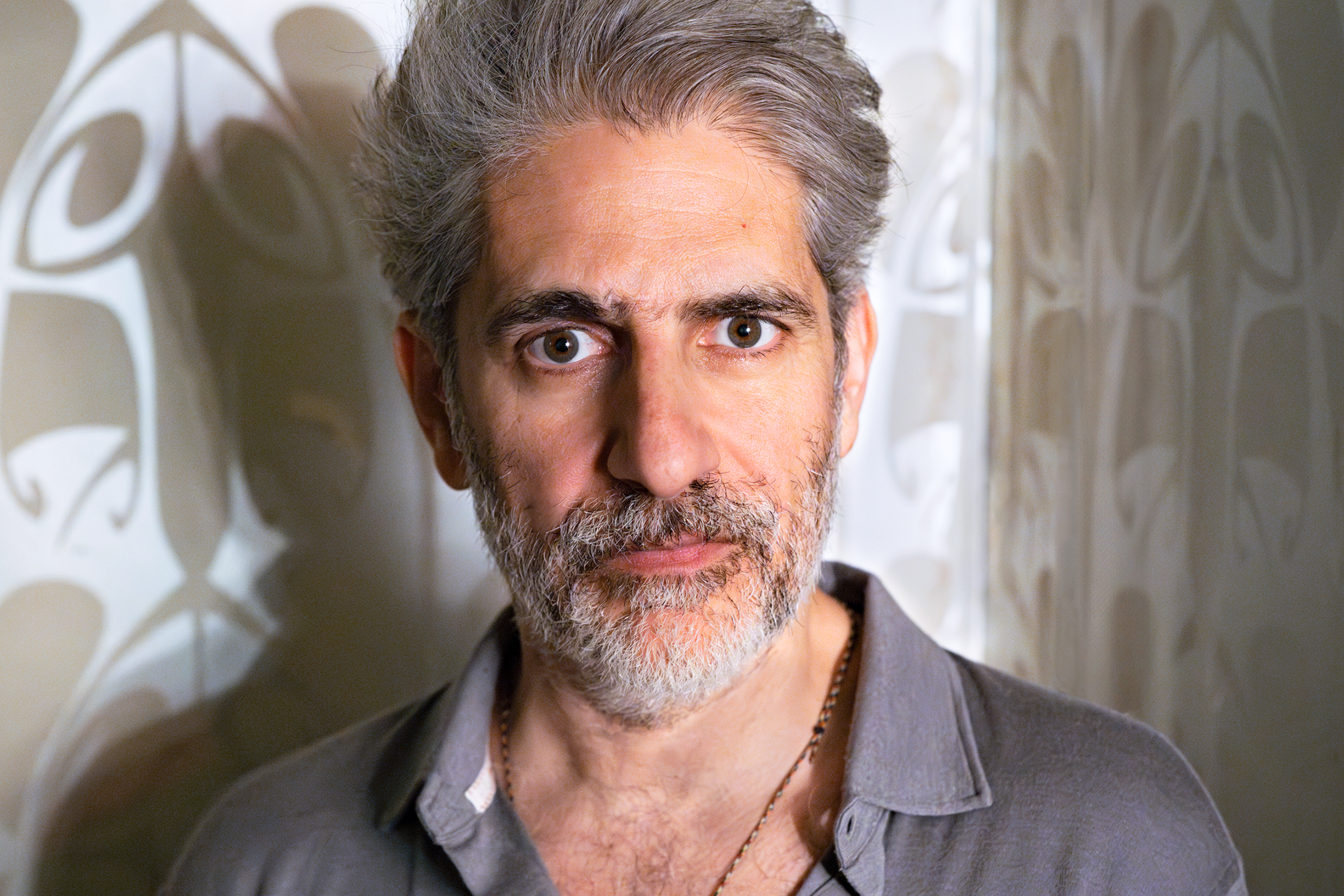

There are many moments in the reality show that expose the human tendency to indulge our worst impulses, but here was one that felt like it had the potential to break patterns of behaviour. Of course, nobody listened to Fry’s suggestion and instead Ross successfully led a witch-hunt against Clare Balding, who was swiftly banished. It is impossible to know but it felt like, had they not allowed themselves to be manipulated before the roundtable, the Faithful might have privately reached the conclusion that the man who seemed almost the picture of a Traitor leader – in a check cloak and fingerless gloves, or taking out his foes in a military jumpsuit – was in fact just that.

The problem with The Traitors is that nobody wants to point the finger at someone they believe is on their side. It’s what makes the show work as a near-perfect simulation of real-world tribalism and that of the internet: a false reality where an “us vs them” mentality tricks us into thinking that people like us are innocent and the enemy lurks elsewhere.

The Traitors creator, Marc Pos, is a Dutch TV producer who was the first director of Big Brother, a social experiment about human behaviour that originated in the Netherlands and became an international hit. The inspiration behind The Traitors, initially called The Mutineers, was the voyage of the Batavia, the Dutch East India Company vessel shipwrecked in 1629. After the survivors came ashore, on islands off the coast of Western Australia, a mutiny ensued, but passengers didn’t know who was in favour of mutiny and who among them was lying. (The dispute resulted in a bloody massacre, in which around 125 people were killed.) Beyond this historical context, The Traitors adopts a fantastical concept, but Pos believes the reason the show works is because of the modern zeitgeist, saying in an interview that “with social media and the news, there’s this thing going on about trust now”.

Jonathan Ross’s villainy flourishes in plain sight

That pertinence has become even more obvious in the three years since the show launched in the UK. Online, we are all being directed in a game that we cannot control. Each of us believes that we are too smart to be deceived, but as the rules constantly change it is easy to lose our footing. I thought I was too digitally literate to be duped by images obviously conjured by AI, then recently fell for a video of a kangaroo at a departure gate holding a boarding pass.

Conspiracy theories flourish in environments where the truth is diluted by misinformation and evidence is distorted to push a narrative. On the internet, as in the Traitors castle, it is hard to keep up with what is being fed to us as a distraction and what is true. Who gets to define what is real? When we try to point the finger at who is lying, we often get it wrong; or, when we land on the truth, diversion is employed by bad actors to push our attention elsewhere. In our paranoid, post-truth moment, we look to our gut instinct to guide us, as though that emotional response is resistant to external influence.

One of the shrewdest contestants in Traitors history so far was season two’s Jaz Singh, who correctly suspected Traitors Paul and Harry and rejected the groupthink that saw them protected because of their popularity. Singh was not from one of the professions that contestants claim make them great at reading people (psychologist, chess player, actor, magician), but a sales manager who could spot a liar because his father had revealed that for years he had been hiding a secret family. This season, Joe Marler has proven a better Traitor-spotter than his fellow Faithful, nailing Ross and, ahead of the final this evening, airing his suspicion about remaining Traitors Cat Burns and Alan Carr. Marler is a rugby player with experience of working as part of a team and withstanding mind games from an opponent – like Singh, he may have something to teach us about the types of intelligence that can counter misinformation and deception.

Much has been made of how The Traitors is a psychological experiment – as though it has no relation to how we are already behaving, especially on the internet. But last week Boris Johnson, whose own flexibility with the truth is Olympic standard, wrote of how the series “exposes the human flaw that makes us blind to villainy”, arguing that “our refusal to call out evil when the facts are seemingly unmistakable” allows “bad people sometimes to flourish in plain sight”.

Johnson points to Carr laughing when questioned by Celia Imrie about her true identity as one of these supposedly unmistakable facts, but beyond voting and murder patterns there are very few absolute facts on The Traitors. Numerous Faithful have been voted off for behaving strangely under questioning. The contestants behave just like we do on the internet, feeling around in the dark for who to trust and believing there’s safety within the herd. The Traitors mirrors our present moment by proving that “facts” are often little more than hunches and biased impulses, either massaged to prove what we want to believe, or cast aside to ignore what we don’t.

In the non-celebrity version of The Traitors, contestants playing for life-changing money (in the celebrity version, the prize is donated to charity) often crumble as they feel manipulated and unsure. The emotions provoked by being lied to or else deceiving others often means they have to remind themselves this is “just a game”, even as it looks less and less enjoyable. That innocent proposition sounds a lot like the early promise of social media: a game that once felt like harmless fun, but now feels like it has been taken out of our hands.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photographs by Euan Cherry/Studio Lambert/BBC