If a horse is required, it is best to make its presence optional. Premieres are one thing, but securing future performances, even without livestock, is a struggle for any composer. That said, Oliver Leith’s Garland – described as “a processional work for solo soprano, vocal consort, mixed choir and large ensemble, to a text by Charlie Fox in collaboration with the composer” – has already attracted inquiries from Europe after its world premiere on two evenings earlier this month. This long-awaited event was commissioned by Bold Tendencies, who in the same week won a Sky Arts award in recognition of their innovative programming.

Born in London in 1990, Leith catches the imagination with his long-breathed, deeply felt works. His Last Days (2022), a meditation on the death of Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain, returns to the Royal Opera’s Linbury theatre in December. The cast will include Patricia Auchterlonie, who was the soprano soloist in Garland, filling the urban air in Bold’s multistorey car park in Peckham, south London, with ever more ethereal melismas. Garland is unlike anything but itself. The idea, loosely, is of an annual communal event, a festival, with a quality of ritual. Harrison Birtwistle had a similar concept but a contrasting sound world for his Endless Parade (1986), comparable only in its brilliance of spatial invention.

Edward, a “dun-coloured Welsh Section D who stands 14.2 and is thick-set with hairy legs”, was optional but vital

Edward, a “dun-coloured Welsh Section D who stands 14.2 and is thick-set with hairy legs”, was optional but vital

Leith’s music at first appears simple. He uses familiar ingredients: chord sequences that move with recognisable harmonic progressions, in identifiable keys. Garland starts with a piano playing in E flat. It sounds solid, like a school hymn, but the pulse keeps shifting and the pianist, Siwan Rhys of GBSR Duo, is required to whistle to herself while playing. Glassy, perfectly tuned string chords are likewise pushed to microtonal distortions until they disintegrate. An enlarged 12 Ensemble and the elite vocal ensemble Exaudi, together with the conductors Jack Sheen and Naomi Woo, completed this unquantifiable endeavour.

As well as a volunteer community choir, Garland specifies five metal shopping trolleys filled with bottles; 40 whirly tubes (in B and G); a ghungroo; sawn scaffolding poles; five hot water bottles; and a leather whip at least 6ft long. The feel was mostly celebratory, though Section VIII of the hour-long work is called Crash: Twisted Metal and was ear-shattering. Fox’s short text is poetic and allusive: “words go up like smoke flames under a melted leopard orange sky”. As for Edward the horse – technical definition: “dun-coloured Welsh Section D who stands 14.2 and is thick-set with hairy legs” – he was indeed optional but also vital. His placid arrival, advancing with a nonchalant clip-clop up the concrete ramp once used by cars, proved an unexpected and climactic consolation.

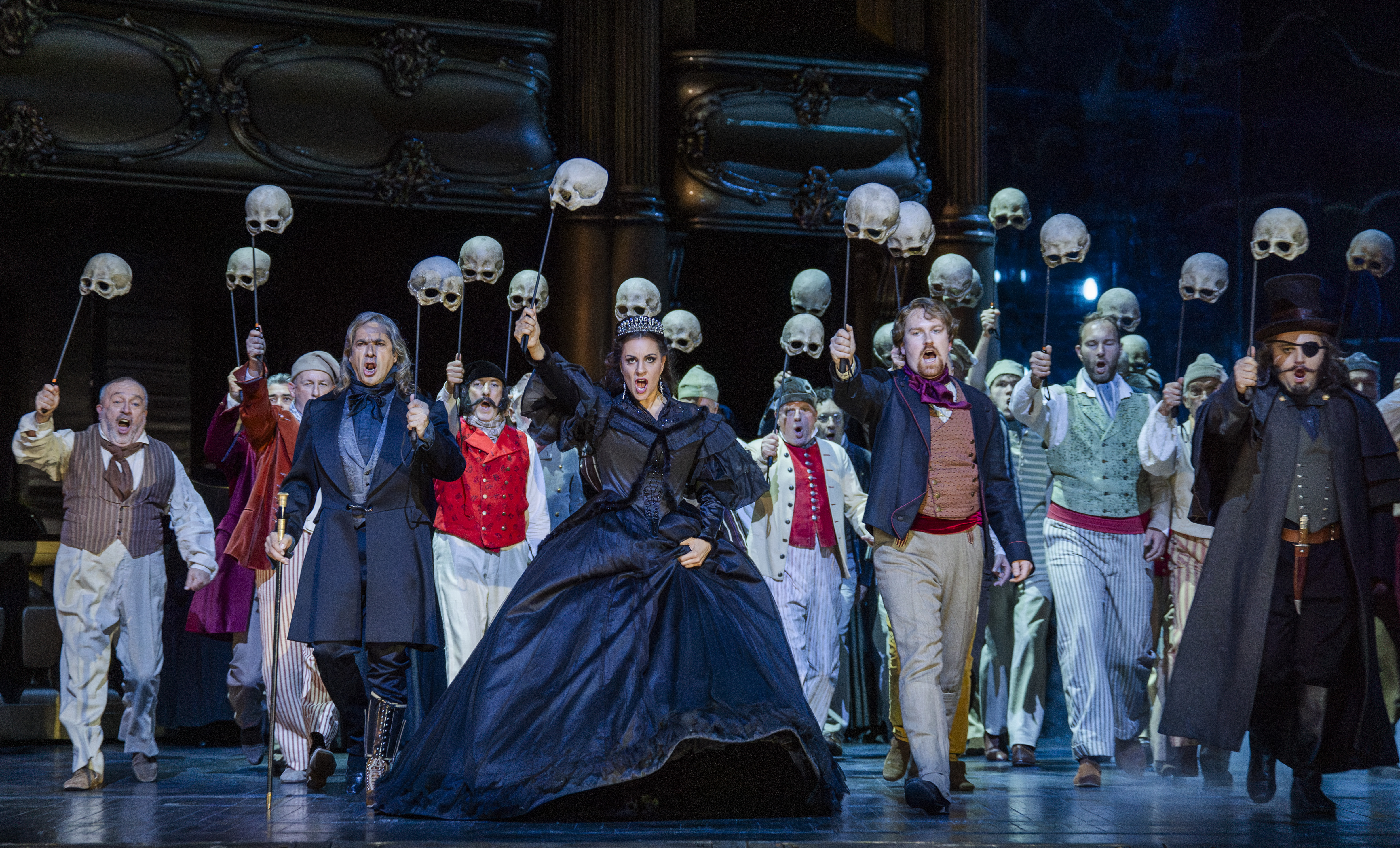

‘Magnificent arias, ensembles and choruses’: the cast of Verdi’s The Sicilian Vespers at the Royal Opera House

No hooves but many ballet slippers and plenty else filled the stage for the Royal Opera’s Les Vêpres siciliennes. Verdi’s five-act opera opens with a Degas-inspired tableau in Stefan Herheim’s 2013 production (revival director Dan Dooner). Written mid-career, after La Traviata but with the glories of Simon Boccanegra and Don Carlos yet to come, The Sicilian Vespers includes a separate 40-minute ballet (omitted here, for which much gratitude; the evening already lasts four hours) as expected in 19th-century French opera. Verdi also made an Italian version but remained dissatisfied with the work, an amalgam of historical drama, parental love and romantic sacrifice.

Containing magnificent arias, ensembles and choruses, it has its devotees. The Royal Opera’s principal guest conductor, Speranza Scappucci, making her debut in the post, put the strongest case, with a cast led by star singers Joyce El-Khoury, Quinn Kelsey and Ildebrando D’Arcangelo. The most striking performance vocally, less so dramatically, was that of Valentyn Dytiuk. The 34-year-old Ukrainian tenor, warm and lyrical,has sung in many smaller houses but is now getting work in, notably, Berlin and Prague. This was his Royal Opera debut.

At Wigmore Hall, the 125th season has launched with characteristic flair, embracing baroque and contemporary, art song and jazz, banjo and kora in the first weeks alone. The Russian-German pianist Igor Levit, playing Schubert, Schumann and Chopin, was one of many big names. He has a monastic approach to performance, head close to the keyboard, body still, face inscrutable. Occasionally he waves an arm out, but mostly drives all vigour into his fingertips. He was never likely to make Schubert’s late, much-loved B flat piano sonata D960 sound as you might have heard it before.

Taking the opening moment at risky leisure, he shaped each detail as if turning over a precious stone and holding it up with wonder. It might have maddened some who know what they like (including the friend who rang me up next day, exasperated). With a big thinker such as Levit, you have to enter his brain as well as Schubert’s. It’s part of the unrivalled excitement of live performance.

The Sicilian Vespers is at the Royal Opera House, London, until 6 October

Photograph by Dan John Lloyd/Tristram Kenton

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy