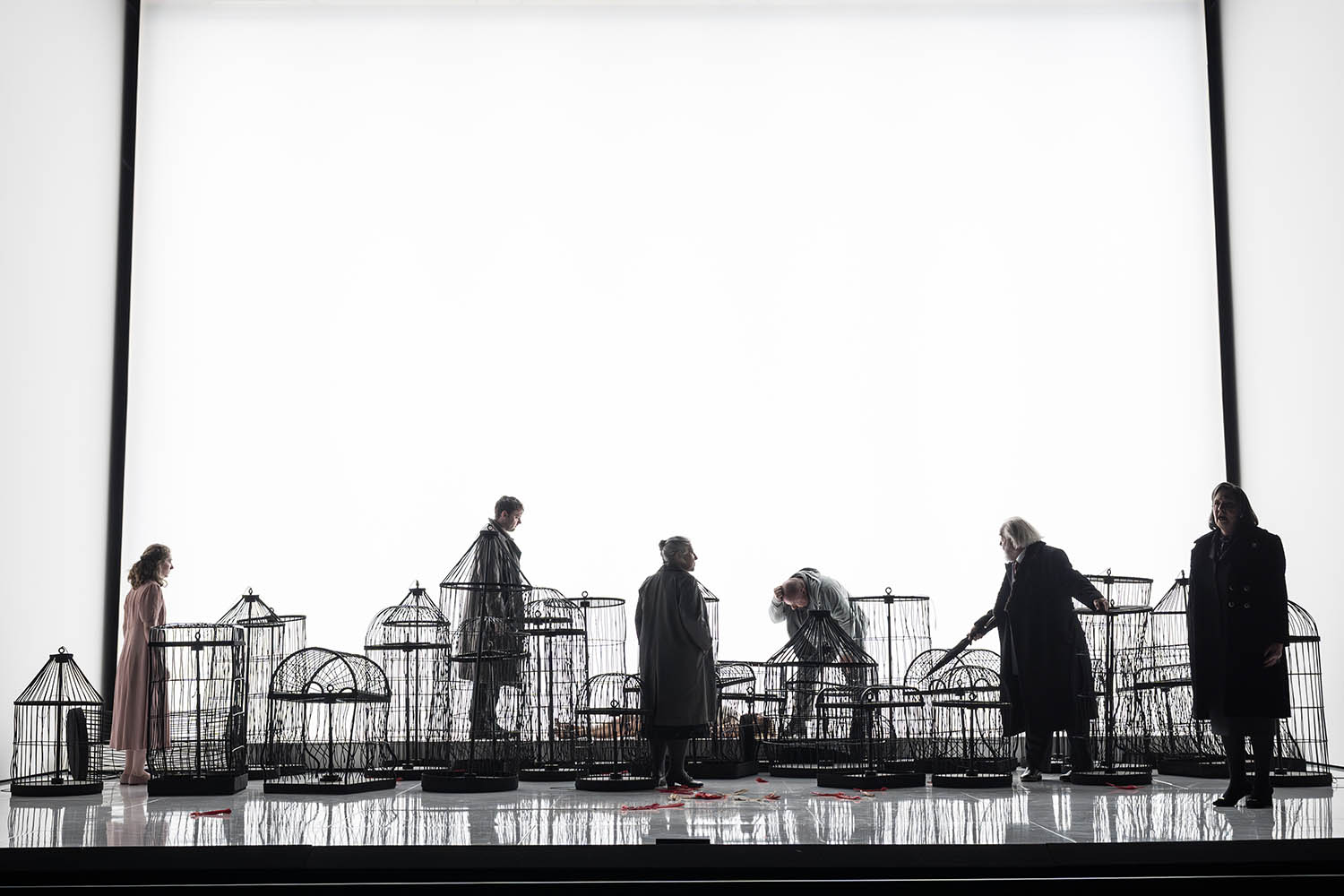

Domestic life is absent from Glyndebourne’s production of Kát’a Kabanová (1921), Janáček’s tragedy of crushed desire. In Damiano Michieletto’s staging, the outdoor naturalism of a Russian village has been replaced by bleak, interior beauty (designed by Paolo Fantin). High white walls, a shaft of light, a winged angel and multiple birdcages tell us, with underlined avian symbolism, that we are inside the trapped mind of Kát’a herself.

Conducted with urgency and nuance by Glyndebourne’s music director, Robin Ticciati, Kát’a is the last of the East Sussex festival’s six productions to open this year. Revived for the first time, it was new in 2021, when Covid restrictions meant the orchestra had to be reduced in size. To hear it full scale, with the London Philharmonic fashioning each shard-like detail, was a reminder of the work’s force, as well as the quality of nervous, straining lyricism so characteristic of Janáček.

The staging, revived by Eleonora Gravagnola, is now more streamlined. If you dislike literal imagery – and this Kát’a has divided opinion – you will bristle. I found it, mostly, elegant and perceptive. Kát’a, unhappily married and seeking freedom, is the pivot. Stained with the guilt of an illicit passion, she cannot escape her fate. Other characters, sharply defined and well sung by all, swirl around her like specks of dust.

Kateřina Kněžíková as Kát’a, Nicky Spence as Boris and Miryam Tomé as the winged angel

This apparent imbalance mirrors Janáček’s own libretto, based on Alexander Ostrovsky’s play The Storm. Inspired by his own unrequited love for a younger woman, Kamila Stösslová, Janáček’s preoccupation is with his heroine. He called the opera one of his “most tender” works.

Kateřina Kněžíková, returning to the title role at Glyndebourne, has immense vocal power but her particular gift is to express vulnerability. She embodied her character’s lost hope. Both her husband Tichon (Jaroslav Březina) and her lover Boris (Nicky Spence, who sang Tichon in 2021) are hapless dead weights. They are neither hero nor villain. Their failure to understand, let alone match, her dreams is part of the tragedy.

The outdoor naturalism of a Russian village is replaced by bleak, interior beauty

The outdoor naturalism of a Russian village is replaced by bleak, interior beauty

Sam Furness and Rachael Wilson, as the young couple Kudrjáš and Varvara, combined gentle anxiety and unfettered innocence. As the mother-in-law, Kabanicha, Susan Bickley revelled in nasty piety, strutting with the sleek menace of a hooded crow. Bickley is supreme in this role. Her sofa frolic with the prosperous merchant Dikoj (John Tomlinson, shuffling on his knees with his shirt off) had tacky and chilling allure. The pairing of these two veteran singers was one of the evening’s strengths. Kát’a Kabanová will never offer comfort, but its restless poetry, as with its composer’s entire body of work, lodges itself within us and won’t let go.

The other late production at Glyndebourne, now halfway through its run, is Verdi’s Falstaff, in Richard Jones’s ever witty and joyous 2009 Metroland staging (designed by Ultz) and conducted by Sian Edwards. Brownies in uniform and muscular Eton rowers populate the stage. Betjemanesque mock Tudor is the aesthetic.

Anna Princeva’s Alice Ford leads a lively group of bored Windsor wives, with a radiant cameo from Mariam Battistelli as Nannetta. Verdi makes fiendish demands on singers; ensemble was somewhat approximate the night I went, but the great compensation was in Renato Girolami’s portrayal of the title role. His Falstaff, never grotesque, commanded rare sympathy while also being idiomatically and precisely sung, and funny.

‘Betjemanesque mock Tudor is the aesthetic’: Verdi’s Falstaff at Glyndebourne

On the evidence of several evenings spent in a packed Royal Albert Hall, and by hearsay away from it, the BBC Proms are enjoying a triumphant and well-attended season. This past week Mahler dominated, with a spacious account of the Symphony No 2, Resurrection, given by the Hallé orchestra, choral forces and soloists (heard on BBC Sounds). Making his proms debut, the Hallé’s principal conductor, Kahchun Wong, showed his authority in this large-scale 80-minute work, in which catastrophe is never far away, and redemption hard won.

Two nights later, Mahler’s youthful oddity, Das klagende Lied, was paired with Boulez: his Rituel in memoriam Bruno Maderna (1974-5), superbly negotiated – the only word for a piece in which eight groups play at different pulses – by the BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Hannu Lintu. The Mahler, the original version written between 1878-80 when he was in his late teens, was despised by both Brahms and Liszt, who generally agreed on nothing. A macabre gothic horror saga, it is based on Grimms’ tales, with a murdered brother and a flute fashioned from one of his, to quote, “sticking out” bones. With the BBCSO and Constanza Chorus, soloists Natalya Romaniw, Jennifer Johnston, Russell Thomas and James Newby, as well as alto and treble talents Malakai Bayoh and Carlos González Nápoles, plus an offstage band in the gallery, it was an ideal Proms extravaganza. I am not clamouring to hear it again, ever, but you won’t find it done better.

Kát’a Kabanová and Falstaff are at Glyndebourne festival opera; festival runs until 24 August

Photographs by Marc Brenner/Bill Knight

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy