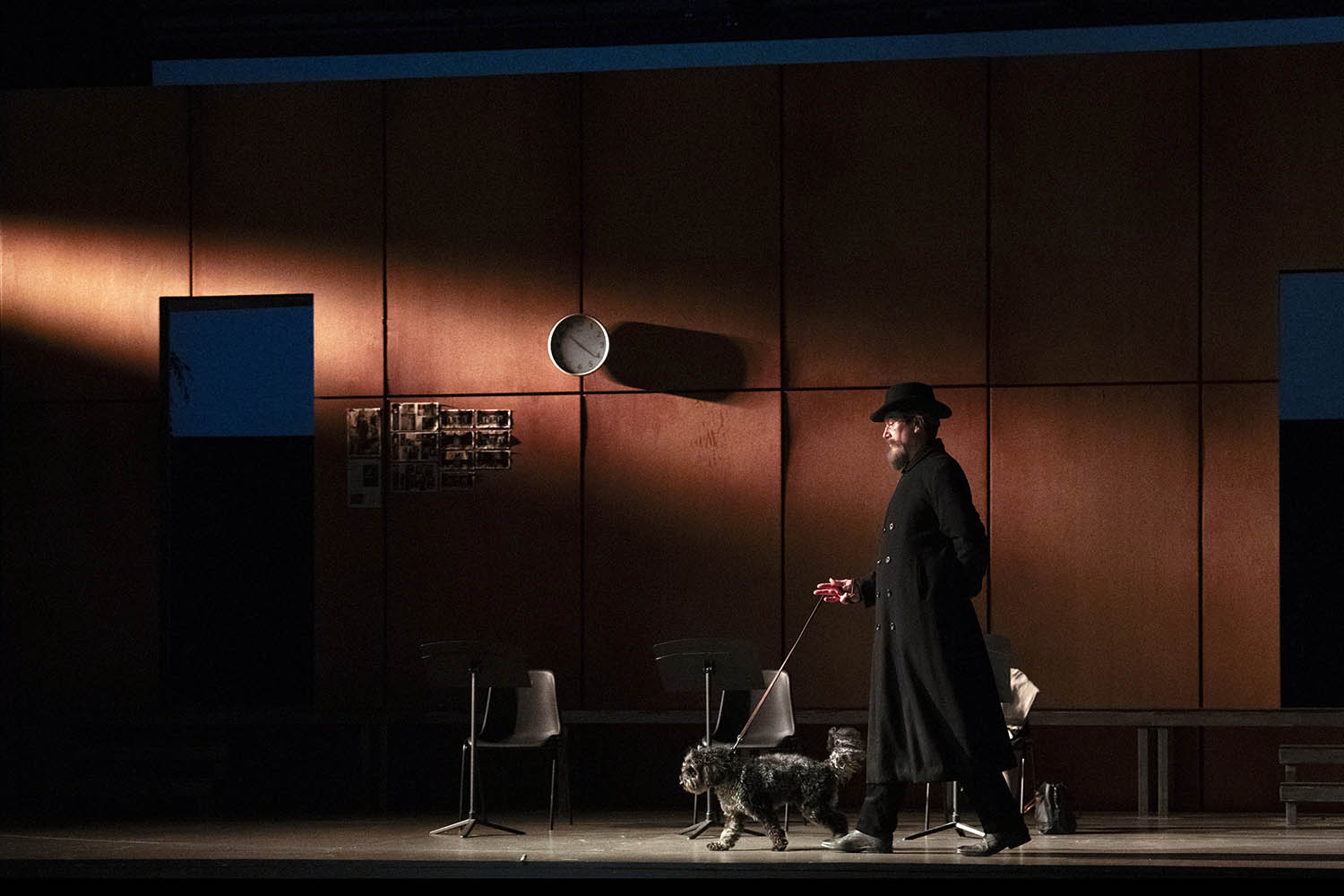

Let’s start with the dog. Chekhov owned a pair of dachshunds; A Visit to Friends, the new opera based partly on his short story of that name, featured one cockapoo, who walked on and off at the beginning with a ghostly figure dressed as the Russian writer himself: Homburg hat, pince-nez, goatee beard. The world premiere of this 90-minute work, by the composer Colin Matthews to a libretto by the novelist William Boyd, opened the 76th Aldeburgh festival at Snape Maltings last weekend. (Named Shosty, you will wish to know, after Shostakovich, the dog is co-owned by the production’s director Rachael Hewer and the credited dog-handler-cum-composer, Mark-Anthony Turnage.)

This is the first opera, six years in the making, by the otherwise prolific Matthews, 79, who early in his career assisted Aldeburgh’s composer founder, Benjamin Britten, and has since been a central figure there, not least in mentoring generations of young composers. William Boyd, in his first libretto, has proved an ideal partner: his text is crisp, well paced, never too wordy. An immediate regret is that, after two performances, enthusiastically received and expertly performed – by Aurora Orchestra and soloists, conducted by Jessica Cottis – no further run has been announced. It was as engaging as any recent new opera except perhaps the Royal Opera’s Festen (2025) by the otherwise preoccupied dog-handler Turnage.

To say A Visit to Friends is based on two Chekhov stories (the other being My Life) is to simplify, somewhat. Boyd reworked his own play Longing (2013) and at Matthews’s request added the context of an opera rehearsal, two timelines and three characters, both “real” and imagined, with similar names, who are variously and unsatisfactorily, actually or theatrically, in the past or the present, in love with each other. There is also an imagined lost opera by Chekhov’s acquaintance, the composer Scriabin (1872-1915): some of Matthews’s music is a reworking of Scriabin’s fourth piano sonata. Confused? There was a reason to start with the dog.

It is no more odd, as a few pondered the next day, than a new film made in black and white or a painting inspired by an old master

It is no more odd, as a few pondered the next day, than a new film made in black and white or a painting inspired by an old master

Thanks in part to the imaginative and streamlined direction by Hewer and a handsome, efficient set by her regular collaborator, the Dutch designer Leanne Vandenbussche, all was crystal clear. Action revolved between a rehearsal room that, on the reverse, became a Russian dacha – grey walls, white paintwork, classic summerhouse veranda. The protagonists stepped through a door from one world to the next: one moment with a mobile phone in hand, the next swathed in a Cherry Orchard atmosphere of 1903-4. (The story, A Visit to Friends, is thought to have been a starting point for that play and shares its yearning mood.)

The work’s impact lies chiefly in the force of Matthews’s score, cast in the late romantic style of Scriabin but speckled with Matthews’s own taut techniques. It is no more odd, as a few pondered the next day on the Aldeburgh seafront, than a new film made in black and white or a modern painting inspired by an old master. We find either of those less problematic, but our reactions to music, beyond liking or disliking it, are always more obscure. Do we like it because it sounds like Scriabin, whose music we might only slightly know, or because it doesn’t sound, as we may negatively have expected, like difficult “modern opera”? Matthews has created something distinctive and effective. The style is exactly right here, even if he never writes anything like it again.

‘Innocence and desire’: Marcus Farnsworth (baritone) and Susanna Hurrell (soprano) are caught in a tangled love triangle in the new opera at Aldeburgh

Harnessed deftly to Boyd’s text, sung with clarity of diction by the main principals – Susanna Hurrell (soprano), Lotte Betts-Dean (mezzo), Marcus Farnsworth (baritone) – the opera at once flowed and drew you in. The omnipresent “director” Gregor (Edward Hawkins, bass) and an onstage rehearsal pianist (Gary Matthewman) brought quiet humour, acting as emotional counterpoise to the love triangle tangle as it grew more knotted. The piano also added colour to the score’s densely harmonised strings and low woodwind – notably alto flute, cor anglais, bass clarinet, bassoon – as well as horns and harp. As Marcus/Misha, indecisive in matters of the heart but loved both by Varia/Vanessa, and by the young newcomer, Nadia/Natalie, Farnsworth conveyed just the right air of annoying self-righteous indecision. Hurrell, bright-voiced and alert, mixed innocence and desire. The major role was that of Varia/Vanessa who, in a heart-rending final aria, reflected on a lost past with Misha/Marcus. Betts-Dean gave full rein to this vividly Chekhovian sense of wasted longing. Indeed, Chekhov’s ghost and the director’s dog reappeared at the end and brought all to an affecting close.

Aldeburgh’s busy opening weekend, Andrew Comben’s first as director and chief executive, ushered in a fortnight of 20 premieres and a variety of ensembles and artists. In addition to the opera, a substantial work by festival composer Helen Grime, Folk (2024), stood out. Played by the Knussen Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Ryan Wigglesworth and superbly sung by Claire Booth, this dark setting, brightened by a clamour of various bell sounds, explores enchantment, ritual, violence, to a text by novelist Zoe Gilbert. Allan Clayton, a festival artist, sang Britten’s Nocturne with close attention to detail and impeccable intonation.

In the Britten Studio, pianist George Xiaoyuan Fu, with the tireless Betts-Dean, explored solitude and Schubert (also via a film by Matilda Hay), with Fu bringing youthful insight to the piano sonata in B flat D960.

The sonata, one of the composer’s final compositions, is generally revered as a work of saturated elegy, but Fu’s fresh approach, especially in the sprung rhythms of the scherzo, challenged this conception.

And at Blythburgh church, the small vocal ensemble Exaudi performed director James Weeks’s sequence A Book of Flames and Shadows, built around Franco-Flemish renaissance madrigals. The percussive syllables of spoken Italian subtly turned to music as the sun went down over the marshes.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

76th Aldeburgh festival, Snape Maltings, Suffolk, runs until 29 June

Photographs by Richard Hubert Smith