Portrait by Pål Hansen

Baxter Dury, tall, lanky, hair more salt than pepper, is sitting in a west London cafe near the river. He’s too tall for the cafe table: his legs fold in half as if his knees are spring-loaded. We’re talking about him losing his driving licence a few months ago: a story that involves the Radio 2 presenter and vigilante cyclist Jeremy Vine spotting Dury using his phone while driving.

“It was in a traffic jam and I was on Instagram,” says Dury. “I know, it’s terrible. He filmed me and I got done and it was in loads of papers! It was funny because they couldn’t really work out who I was.”

Dury, to his fans, is indie’s roué word-conjuror, the self-styled “nylon panther” whose rumbling close-to-the-mic observations, melancholy melodies and hip-hop undertow have built a loyal following over two decades. But to the tabloids, he’s merely the not-as-famous son of the late Ian Dury, of Ian Dury and the Blockheads and Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick fame. And when he went to court for his driving offence, the magistrate got excited and said she, too, was an Ian Dury fan. So Baxter leaned into his status to try to get off his charge – “I was thinking: nepo credits, nepo credits” – saying how truly wonderful his father had been, and how he himself had a successful music career that would be adversely affected by a driving ban. He was winning the magistrate over, until a clerk showed her Vine’s video, and that was that. Licence gone. He’d only got it that year.

“I shouldn’t make an anecdote about losing your licence,” says Dury, “but it made me wonder about the way I am. How I fall sometimes into luck and sometimes not, and it’s all so close to each other… It’s an inherent thing in me. I’m on the edge of trouble and success at any given moment.”

You can feel it: Dury is somehow relaxed and wired at the same time. In his videos, he plays a man who appears to be a winner but isn’t: a hero being smashed in the face in a boxing ring, or getting a sexy dance from Death at a late night bar, or wandering angry and abandoned on a Miami beach. He’s charming company, funny and smart, but there’s a sense that, under different circumstances, the wolf might show his teeth. The pain might bleed out, the madness arrive.

“I attract the madness,” he agrees. “I am it. Definitely. Yes. I was born in the ashes of true bohemian-ness. No matter how normal I am – and I’m relatively day-to-day normal – I’ve also got one eye open looking for some kind of excitement. Not Jekyll and Hyde. More Sherlock and Watson.” Sherlock and Watson implies insight and ignorance, and when it comes to songs, Dury’s remit is, he shrugs, mostly “failed male ambition, failed masculine toxicity, though I hate those words”. His biggest hits combine menace, ennui, heartbreak and humour with an off-centre, devastating turn of phrase. “Breakfast imposter, leisure-seeking honey-sucker” (Celebrate Me); “I’m at the hotel with the Haribo-faced Britons” (Crashes); “I’m the sausage man / The shadow licker / I’m the tiny little ghost / That features in your despondent moments” (Miami); “Who knows better than the boy who never listened to anyone?” (Glows).

His latest album, Allbarone (pronounced “Al-barr-own-ey”), out in September, is a proper banger. Written with super-producer Paul Epworth, known for his work with Adele and Rihanna, it’s packed with catchy hooks and a get-thee-to-the-dancefloor feel, as well as Dury’s usual gimlet-eyed commentary. It came about because Epworth saw Dury play Glastonbury’s Park stage in 2024, and wanted to see whether what Dury calls his “shop-soiled” talent would work with dance music. Dury was happy to oblige. “It’s so much more enjoyable when the audience are dancing and not thinking,” he says. “They’re more spasmodic, and I relate to that.” (Also, his biggest hit so far has been the brilliant These Are My Friends, a 2022 collaboration with electronica star Fred Again, which perfectly describes the intense connections made through raving.)

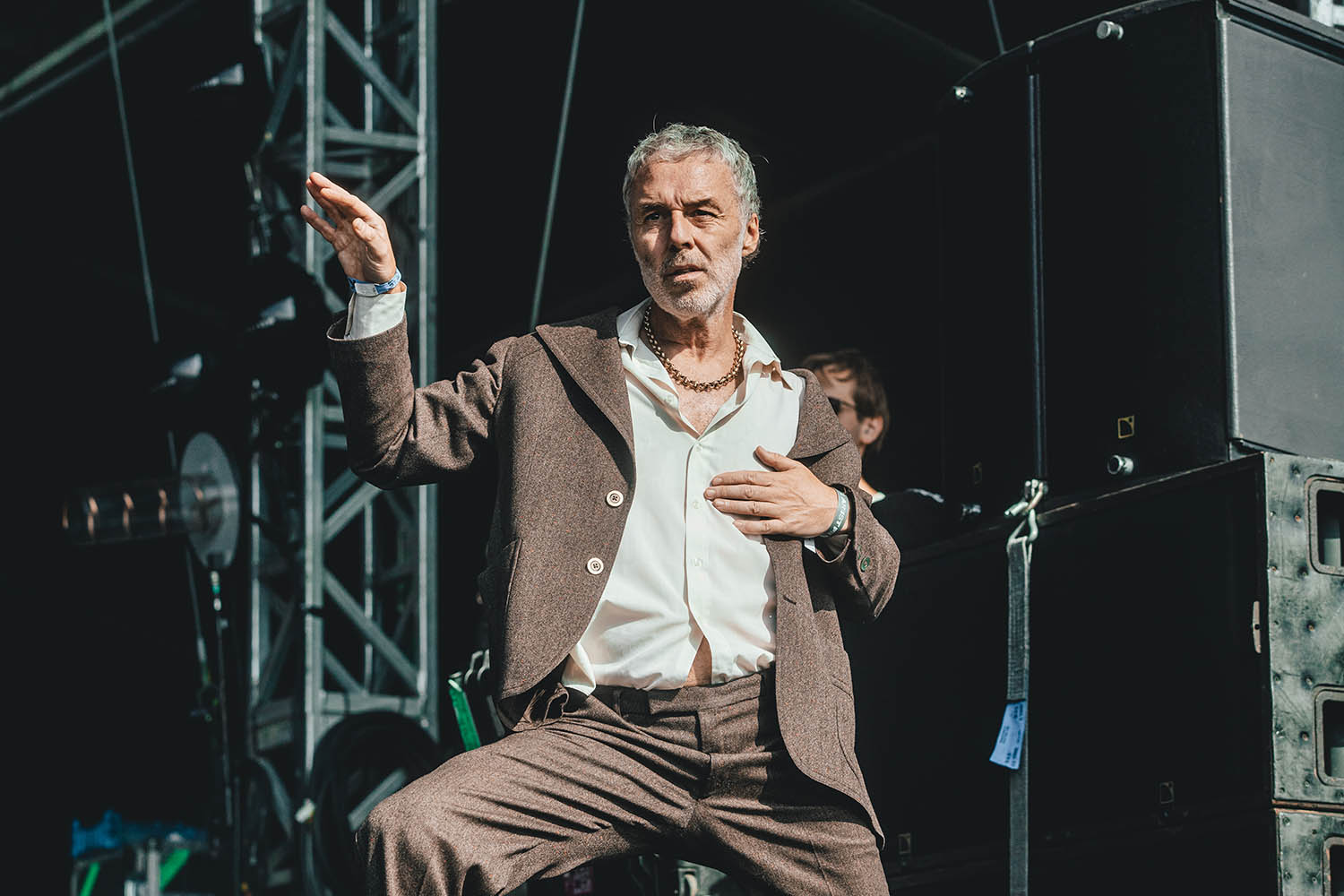

Dury performing at Tramlines festival in Sheffield in July

Dury enjoyed the recording process. Usually, he’d write both words and music, but Epworth wasn’t interested in that. “To be honest, when I got there and played my tunes to Paul,” says Dury, “he didn’t even acknowledge them. He was looking at his Apple watch, doing something else, sending his dog to therapy.” Instead, Epworth constructed tracks and then Dury wrote lyrics in response, tapping on his laptop in the corner. (He writes on a computer because his handwriting is “prison wall stuff, undecipherable madness from a serial killer”.) They were under time pressure, because Epworth’s world is swanky and a big-time studio is expensive, but Dury enjoyed the speed. It’s how he works best, he thinks.

The first single, also called Allbarone, came out in May. Though he sometimes writes words just for how they sound together, this track was based on something that actually happened. Dury had arranged to meet a date at an All Bar One in London, but the evening didn’t go well and, after she left, he found himself sitting alone, outside the bar, in the rain.

“And then I got on the Piccadilly line to go home, with that harsh lighting, and it all got to me. I did shed a tear,” he says. “I was mid-tour, and I was tired. Anyway, the joke that I was repeating when we met, probably one of the reasons why it didn’t work out, was the word Allbarone. ‘We’re in Al-barr-own-ey.’ She must have thought, ‘Knobhead. Bye.’” After he made the song, Dury sent it to the woman concerned. “She laughed about it. On text, at least,” he says, wryly. “‘LOL.’”

His label, Heavenly, has justifiably high hopes for this album. He’s more sanguine.

“I don’t really know if it’s brilliant,” he says. “It might be. Part of my brain doesn’t really care. I want people to like it in front of me, congratulate me, and then I want to move on… My career trajectory has a very slight tilt upwards and it feels quite secure in that way. It’s not meant to accelerate too fast.”

He’ll be touring in autumn, and as part of that, he’s playing the Eventim Apollo in Hammersmith, previously the Hammersmith Odeon. He recently put up a video online of him as a kid on stage there, his dad bringing Baxter and two mates on to do a spot of body-popping and breakdancing. It’s very touching. It’s also a small insight into the strangeness of Dury’s upbringing, the fundamental reason why he’s able to step towards or away from chaos. In the video, he looks both embarrassed and excited; his childhood was a unique mix of privilege and poverty, of mayhem and extremes.

The “incredibly well-read, smart, educated” Ian Dury, with whom Baxter lived sporadically in his teens, was a white-hot force of nature, who refused to let his polio hold him back and whose living circumstances would not pass any child safeguarding policies. Baxter’s mum, Betty Rathmell, was a portrait artist – “just as amazing as Dad” – and Baxter and Jemima, his older sister, mostly lived with her when they were little, in Aylesbury and then Tring. There was no money until Hit Me… and when it arrived, it skewed things. Baxter was at school in London by this point and Hit Me was a provocation to many older kids. He left school with no qualifications.

What did he learn from his parents?

“Their pursuit of what they wanted to do,” he says. “Knowing that things are possible and knowing how to focus, always complete what you start. No matter how sad I am, how broken, I will finish the task. I learned that from them. But also, you’re not programmed like everybody else, and it’s a painful realisation that the small details contribute to a stabler life. That can be a very long and hard process to learn.”

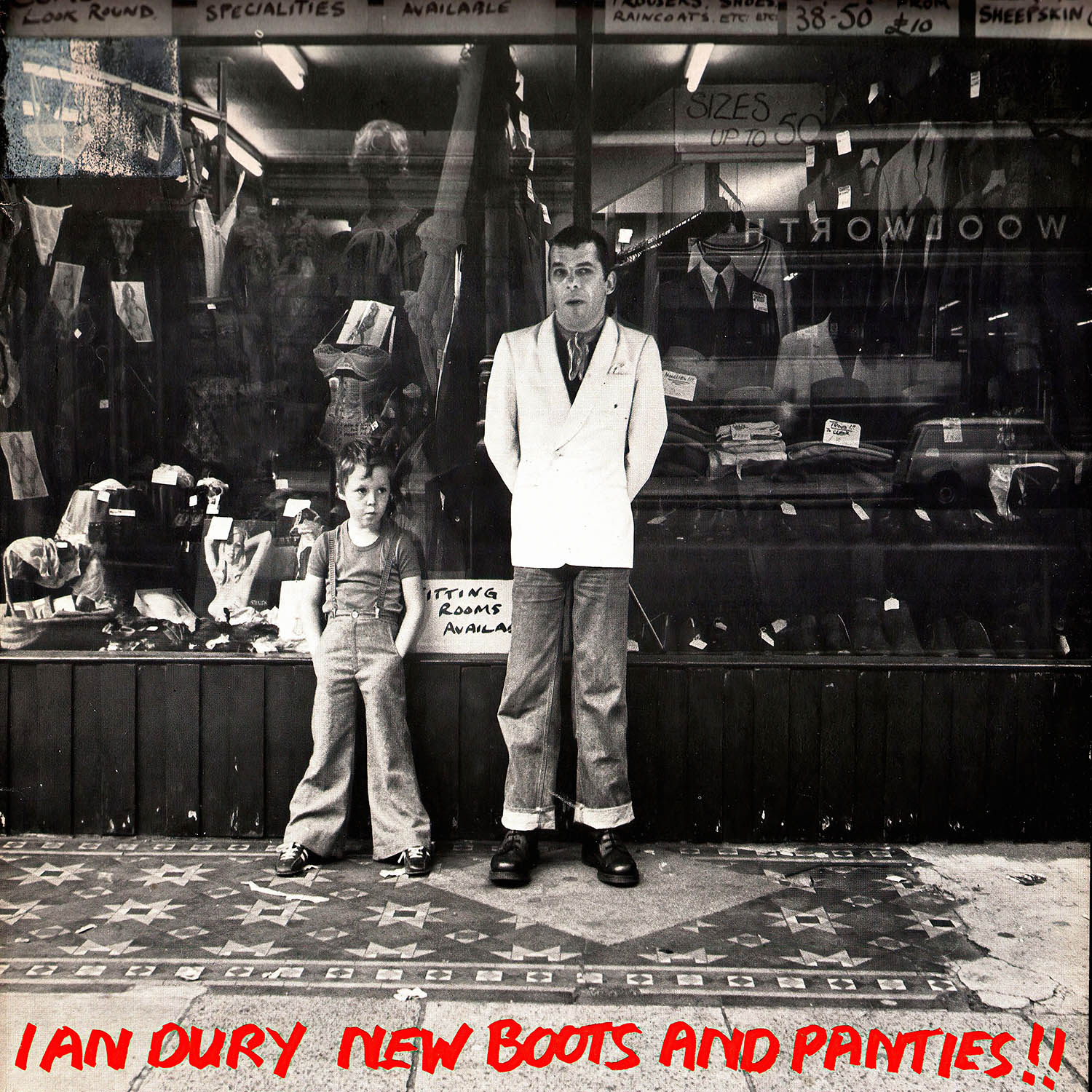

A young Baxter with his dad on the cover of Ian Dury’s 1977 debut album, New Boots and Panties!!

Dury’s excellent 2021 memoir, Chaise Longue, is peppered with characters like the Sulphate Strangler, a 6ft 7in roadie and drug dealer, whom Ian employed as Baxter’s childminder. Over the years, Dury has tracked down people from his past, such as a childhood friend from Chiswick comprehensive. (He wrote Oi, from Prince of Tears, about him. It goes: “Oi, do you remember me? / Broke my nose once / Fucking hurt / … I thought you were great except for the violence.”) When Dury met him as an adult, “I was actually appalled, both by what he went through and what he inflicted on other people. He was a nasty motherfucker.”

Dury didn’t use to like talking about his dad, but these days he doesn’t mind – “the more I carry on, the more I feel at ease with it” – and we end up talking about Ian for quite a while; his complete fearlessness – “the only time he was normal was when he was on stage” – but also how he would grab all the attention in a room and how that can be hard for a child.

In 1996, aged 54, Ian was diagnosed with terminal cancer. He was given a few months to live, but managed to survive for four years. Towards the end of his life, he performed at the London Palladium. He was wheeled on stage in a shopping trolley, “just parked there on the stage,” remembers Dury. “He was pretty nearly dead. And I was sat in a box with Mo Mowlam, of all people, watching, thinking, ‘This is so strange.’”

When Ian died, in March 2000, his family were all with him, including Baxter. His dad gave him various final words of advice and encouragement.

“He told me, ‘Don’t go to Supernova Heights [Noel Gallagher’s house].’”

What?

“Good advice, really, but it’s also showing me that life doesn’t have to become miserable. You can take the piss right up to the last second.” After Ian died, one of his younger sons tied his shoelaces together. Baxter left the house and took the tube home. News had got out, and “there were pictures of Dad with my younger brothers everywhere,” he says. “It was beautiful. Amazing.”

Since then, Dury has met Noel Gallagher and been his support act. He gets on with musicians. He’s hung out with Kneecap, who are on the same label. (“One time they took me to these heavy Belfast pubs. There’s a photo. I’m so drunk I look like I’ve been kidnapped.”) He’s pals with Jarvis Cocker and has made a track with Fat White Family. Actually, when I ask him about how he gets himself into trouble, he uses a Fat Whites gig as a gentle example.

“I was DJing for them and the promoter didn’t give me my cash,” he says. “He said, ‘Oh, can I forward that to you in a week?’ And I was bothered by that, and I was a bit drunk, and so I took his laptop and hid it in a flight case and walked out.” He’s still not quite sure why he did it – “I think it’s justice-related, feeling let down” – but he woke to a lot of agitated phone messages.

At this point, it seems appropriate to bring up that Dury is wearing a T-shirt that says ADHD.

“I don’t know if it’s ethical wearing it,” he says, “because I’ve not got an ADHD diagnosis. But someone in the band recently got diagnosed and he got this T-shirt. And he went, ‘Do you want one?’ I said, ‘Why, do I need one?’ And the whole band looked around and went, ‘You need one.’”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

He’s very focused when we talk, but, he says, he can find himself just walking off when people tell him about a project, or looking at his phone. When you ask him questions, he often goes off on a tangent, as though it sparks something else to think about, rather than an actual answer.

We talk about his dog, a bedlington whippet called Pollo (as in chicken). He found Pollo as a puppy via the internet, located in a Romany camp in Southampton. Dury and his band were in Sheffield, playing the Leadmill, and after the gig, he got the coach driver, Dave, to do a detour to Southampton on the way back to London to pick up the dog. He had to keep it quiet. “The band just wanna get home after gigs, so they’d kick off if they knew.”

They got to the camp at 5am, and parked up. The bus lights blazed through the whole camp and people started coming out. Everyone in the band woke up too, annoyed that they weren’t in London. The puppy owner emerged with his wife – Dury met their horses – and eventually Dury got Pollo, and had to parade him round the bus to the band, to justify the detour. “Oh and the guy’s wife said: ‘He listened to your music. He hates yours, he loves your dad’s.’”

When he’s in London, Dury lives pretty quietly with his son, Kosmo, and Pollo. No relationship at the moment, but he has a lot of friends from his childhood, especially from his teenage hip-hop years. He’s writing a sequel to Chaise Longue, which he’s finding hard “just getting the tone right”. Recently he was offered a part as a life-worn detective in a TV show – astute casting – and he’s been thinking of working that into the book. “There’ll be a bit of truth, and there’ll be bits that aren’t truth, and then maybe I’ll solve a crime, and maybe I won’t, and maybe you won’t be able to tell which bits.”

He’ll get that done and then he’ll think about the gigs, and maybe getting his driving licence back again. When he was at Glastonbury in 2024, he had the most excellent weekend, staying in the house of an 80-year-old ceramicist who drove him through the entire festival in a 1960s Morris Minor, right up to his gig. And afterwards he drove home, along country lanes, listening to the football, and it made him so happy. He doesn’t know if he’ll be able to pass his test again, if he has to take it.

“The first time round there was a great storm and it was all mental and the car nearly got blown off the road, and I think the tester might have been sympathetic,” he says. “It might have been a fluke, I was wondering about that. Maybe I just need really extreme weather again. Then, I’ll ace it.”

Allbarone will be released on 12 September on Heavenly

Photographs by Getty Images