High up in the hills above Los Angeles, an ornate house nestles behind electronically controlled gates. It is eerily quiet save for the soft hiss of sprinklers, the distant hum of traffic. In the back garden, there is a large playhouse and a children’s swing, but no sandpit. On a clear day, when the smog lifts over the city far below, you can probably see the ocean.

Inside, in the front room, a familiar-looking man sits. He is pale, and his voice is slightly slurred. His slippers are arranged neatly just beyond his feet so he can step into them when he pads to the fridge or, occasionally, to play the piano. From time to time, his hands beat out a slow, jerky rhythm on his knees. There is music playing constantly in his head, but he has not written a finished song for four years, nor a hit for nearly 30. He remains, though, a genius. Perhaps, history may yet prove, the only true genius that pop music has produced.

His name is Brian Wilson.

He is talking, fitfully, sadly, about the moment some 30 years ago when his gifts turned into a kind of madness. “I guess, for a while, I didn’t really want to be in the world,” he says, his eyes flitting from me down to his fidgeting hands. “The world was just too scary.” He trails off into silence. “There was pressure, always pressure,” he continues, the words coming in short, breathless salvos. ‘The people I was working with were pressurising me and that kind of scared me away from being creative.”

Those people were the other Beach Boys: his brothers, Carl and Dennis; his cousin, Mike Love; and his friend, Al Jardine. Back in the mid-60s, when pop was young and full of promise, the Beach Boys made music that effortlessly encapsulated that innocence. Then, when pop grew vaultingly ambitious and darkly serious, Brian Wilson responded in kind, creating some of the most musically complex, and saddest, songs ever recorded.

At the height of his creativity, though, Wilson’s genius fled as suddenly as it had blossomed. For nigh-on 20 years, the most gifted Beach Boy retreated, not just from the world of music, but from the world itself. “I was in a bad place,” he says. “I can see that now. Back then, I was just stuck there. Adrift.”

The Beach Boys in 1962: (l-r) Brian, Mike Love, Dennis Wilson, Carl Wilson, David Marks

The Brian Wilson story begins, like all great tragedies, with the sins of the father being foisted on to the sons. A semi-successful songwriter, Murry Wilson was a tyrant who took out his frustrations on his three sons. He once tied his most gifted son to a tree as punishment for a petty misdemeanour. An early beating may have caused Brian’s partial deafness. “I was constantly afraid,” he says. “That’s what I remember most: being nervous and afraid.”

By adolescence, the precociously gifted teenager had learned to escape into music, to turn the melodies in his head into fully formed songs. In the Wilson family home in Hawthorne, California, overseen by the ever present Murry, the three brothers and their cousin began singing in the close harmony style of their favourite gospel group, the Four Freshmen. Carl, the youngest brother, introduced the others to the rhythm and blues of Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry, but it was Brian who merged the two, almost conflicting genres to create a unique sound that, as musician and fan, Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins, would point out 30 years later, “didn’t just eulogise cars, girls and surf, but sounded like cars, girls and surf”.

Between early 1963 and the end of 1964, Wilson wrote 16 hit singles and seven hit albums. As his later collaborator Van Dyke Parks put it: “Brian’s songs personified the Californian sense of place that all Americans used as their dream escape.” The cost, though, to Wilson’s already fragile sense of self was immense. In the studio, he was happy; outside the studio, his life was fraying at the edges. In 1964, he fired his father as the band’s manager and was confined to bed in the family home following his first nervous breakdown.

Replaced for live performances, initially by Glen Campbell, Wilson stayed in Los Angeles, and watched the world of pop shift on its axis. Hanging out with the Byrds and visiting members of the Beatles, he tried LSD for the first time in 1965. As his first wife, Marilyn, later put it: “Brian saw God, and cried for days on end.” You can hear the psychic shift in the spacey, shifting opening chords of California Girls, released that summer. When I ask him if he has any regrets, he answers quickly: “Only one – taking LSD. It really fouled up my mind.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

After hearing the Beatles’ Rubber Soul album on marijuana, and being “blown away by it”, he announced to his wife that he was “going to make the greatest pop record ever”. Then, he set about doing just that. “Pet Sounds was spontaneous,” he says now, his face brightening for the first time since we met. “I felt like I had so much music to get out. I was also smoking a lot. Pet Sounds was me saying, ‘Brian Wilson’s love is yours... ’”

It was also, he says, “an ode to [the producer] Phil Spector”. “I was obsessed totally with Spector, with the energy of his music. That’s why I called the album Pet Sounds – the same initials as Phil Spector.” Now regarded by many critics as the greatest pop record ever made, Pet Sounds was memorably described by the writer Nik Cohn as “sad songs about loneliness and heartache; sad songs even about happiness”.

The rest of the group, though, were dismissive. Mike Love, who clung most strongly to the old ideal of the formulaic pop song, called it “Brian’s ego music” and described some of the lyrics as “nauseating”. The album sold poorly, and eight weeks after its release, Capitol Records rushed out a greatest hits package to compensate.

He began working almost immediately on the follow-up to Pet Sounds, a single song that took six months to complete and cost the unprecedented sum of $50,000. The result was Good Vibrations, in which the old Beach Boys sound – cars, girls and surf – was filtered through a psychedelic gauze that was both mesmeric and intoxicating. “That was a scary record, real scary,” he grins. “It blew everyone away, me included.” Good Vibrations was released at the tail-end of 1966, and shot to the top of the charts in the US and Britain. At 24, Brian Wilson had made his last No 1 record.

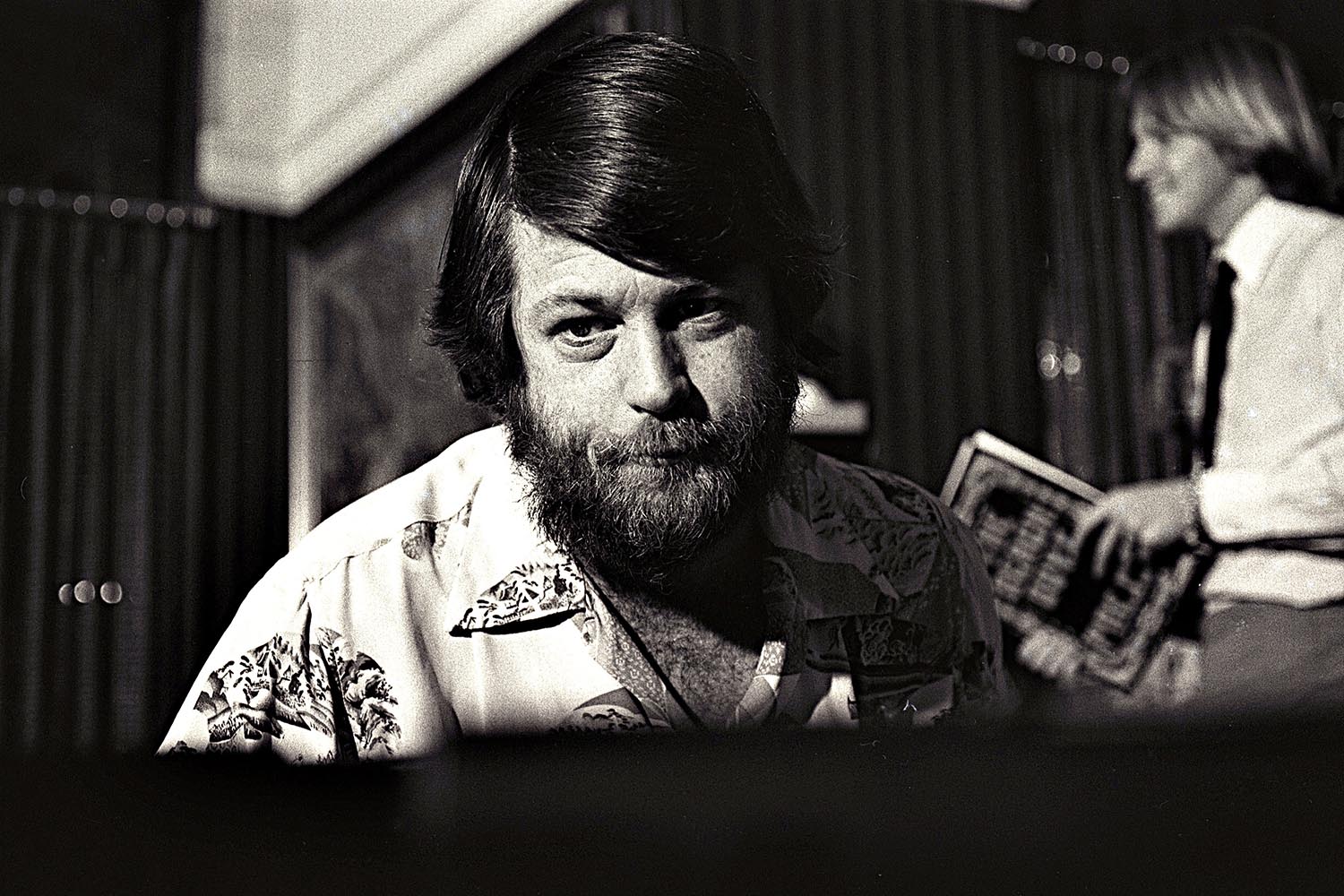

Brian directs the sessions for his magnum opus, Pet Sounds, in 1966.

What happened next is the stuff of pop mythology. With a new lyrical collaborator, Van Dyke Parks, Wilson set about constructing his answer to the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper. The concept album Smile would, he said, be “a teenage symphony to God”. His behaviour, though, was becoming more unpredictable and eccentric. He opened a health food emporium called the Radiant Radish, and would often turn up, stoned and overweight, to do a stint on the till. In his home studio, he had builders construct a huge sandpit in which the grand piano sat. He wanted, he said, “to feel the beach beneath his feet”. Van Dyke Parks refused to work at the piano because he kept stepping on dog shit left by Wilson’s beloved pooches.

Brian’s drug intake was now epic even by the standards of the time: $2,000-worth of hash was purchased to kickstart proceedings on Smile, alongside a batch of LSD and the prescribed amphetamines he now took daily. After a building nearby burned down during the recording session for a piece called Fire, he tried to set fire to the Smile tapes. He spent the next three years in bed, paralysed by anxiety. He played Phil Spector’s Be My Baby over and over: “It was the anointed song.” At times, he heard Spector’s voice taunting him. At other times, Murry’s voice whispered in his ear. “I was paralysed by fear,” he says now. What, I ask apologetically, were you afraid of? “I was afraid of Phil Spector. I thought he was going to kill me.”

The Beach Boys continued to tour without him, but the group was a fractured entity. Dennis Wilson befriended an illiterate ex-con and would-be recording artist who called himself the Wizard and whose real name was Charles Manson. The Beach Boys recorded one of Manson’s songs, the eerie Cease to Exist (as Never Learn Not to Love) for their 20/20 album, changing the lyrics to “cease to resist”, and enraging the author. On 9 August 1969, members of the Manson “family”, high on LSD and fired up by their leader’s vengeful rhetoric, murdered Sharon Tate and four of her friends. After the short summer of love, the darkness had descended on the hippie dream.

That same year, Wilson learned that his father, in a final act of vengeance, had sold the entire Beach Boys’ publishing rights for $700,000, telling his distraught son: “They’re never going to amount to anything.” Wilson remained in his room, writing countless half-finished songs that no one bar his brothers would ever hear.

In 1971, the group released Surf’s Up, the epic title track with its baroque lyricism and shifting, layered melodies, dating from the legendary Smile sessions. It included the song that would become Wilson’s farewell to the fading Californian dreamscape he had helped create. It was called, simply, ’Til I Die. “I’m a cork on the ocean,” he sang, “floating over the raging sea.”

Two years later, Murry Wilson died of a heart attack. Only Carl attended the funeral. By now, Brian’s behaviour was so unpredictable that Marilyn hired Dr Eugene Landy, a psychologist who had successfully treated other troubled stars. Landy’s bullying regime of exercise and health food seemed to work wonders and a slimmed-down Wilson was back on stage with the Beach Boys within months. One critic, though, described his role as that of “a performing bear”. “I wasn’t ready,” he tells me. “It was pressure again. People pushing me. I used drugs to escape. Then they sort of took over.”

In 1984, having been expelled from the Beach Boys two years previously, Brian Wilson was officially diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic and a manic depressive. The doctors also found evidence of brain damage caused by excessive and sustained drug abuse. In the 10 years that followed his diagnosis, Wilson’s life veered constantly between the stable and the surreal. Landy appointed his team of “psycho roadies” to monitor his charge’s behaviour around the clock, and appointed himself as Wilson’s creative collaborator. Then, in 1990, after hearing that Landy had allegedly persuaded Wilson to redraft his will, the family filed suits to regain control of his life. The court ruled that he should not see Landy for three years. “I don’t regret it,” Wilson says of that strange time. “I loved the guy, he saved me … He pushed me beyond my limits and stopped me being fearful of the world.”

I had so much music to get out. Pet Sounds was me saying ‘Brian Wilson’s love is yours… ’

I had so much music to get out. Pet Sounds was me saying ‘Brian Wilson’s love is yours… ’

Since the departure of Landy, Wilson seems finally to have found some degree of peace. His second wife, Melinda, takes charge of his daily regimen of exercise and massage. He is still in therapy. He has made up with his grownup daughters, Carnie and Wendy, whom he did not see throughout the Landy years, and who found success of their own as part of the pop group Wilson Phillips.

In 1991, Wilson won back his 60s songs at a cost of $10m. Two years later, Mike Love sued him for royalties on 93 songs he claimed to have co-written and not received credit for. The court ruled in Love’s favour, and Wilson shelled out $5m. Within a few weeks, they were writing new songs together. It would not be overstating the case to say that, in more ways than one, Wilson does not really exist in the material world.

In 1997, his mother, Audrey, died and his beloved brother Carl died of cancer a year later. He tries, he says, not “to think about the bad stuff too much”, and has learned “to chase the negative thoughts away when they surface”. His face, though, darkens into a troubled frown when he tells me this.

He accepts that his best work is behind him, but finds it “hard to live up to my name. I know I have to,” he frowns, “but I don't think I'm going to be able to do it this time around.” These days, Wilson spends a lot of time “sitting and thinking”, and waiting for inspiration. “I have writer’s block,” he says at one point, out of the blue. “I haven’t been able to write anything for three years. I think I need the demons in order to write, but the demons have gone. It bothers me a lot. I’ve tried and tried, but I just can’t seem to find a melody.”

Those words haunt me for days afterwards. But, in truth, they were not said with any sense of deep regret, more in an almost quizzical tone. It is a tone that sums up Wilson’s relation to music and to the world. He is easily the most humble, as well as the most gifted, musician I have ever interviewed, and this, I think, is part of the reason so much of his life has been spent in thrall to controlling figures less talented than himself.

“I think maybe pop has had its time,” he mused towards the end of our meeting. “Pop music has been exhausted. The innocence has been exhausted. I think we’ve lost the ability to be blown away by music. I mean, who is ever going to blow our minds like Phil Spector did?”

Or, I venture, like Wilson did? He smiles and looks away. “I guess so... I mean, Pet Sounds would be in the all-time Top Five, right?”

I nod, and say: “Top Three, easy. Maybe even right at the top.” He seems genuinely bowled over. “You really think so? Aw, man, that’s something, huh?” It sure is, Brian, it sure is.

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in the Observer on 6 January 2002.

Photographs courtesy of Getty