Illustration by David Foldvari

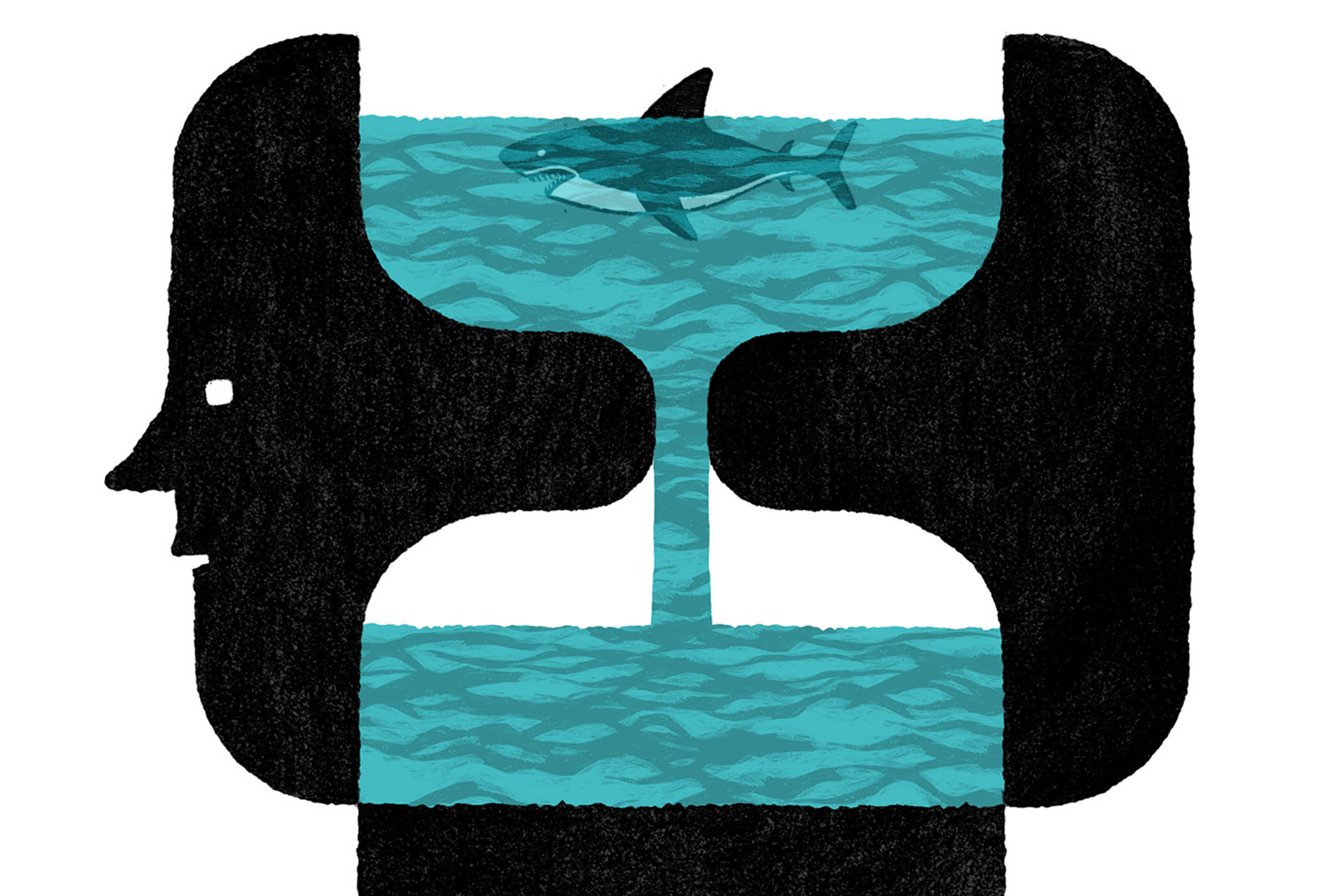

There we are, mouths agape in the dark cinema, my youngest daughter, Alexandra, sandwiched between me and her big sister, 17-year-old Lila. I have taken the girls to a 50th anniversary screening of Jaws. On screen, Hooper dives into the night water, to investigate the ruin of Ben Gardner’s boat.

Like her father, Lila is a long-standing Jaws fan, but with a Chief Brody crush that I find a little baffling in a teenager. She saw the film for the first time at the age of 11 and then insisted on reading Peter Benchley’s novel. That night, she appeared in the kitchen doorway, eyes wide in shock, hands trembling. She had just discovered – spoiler alert – that in the book, Hooper has an affair with Brody’s wife. She will never look at Richard Dreyfuss in the same way again.

It is Alexandra’s debut. She insisted on coming. The Meg had been her gateway and now she’s obsessed with shark films. But this ain’t The Meg, baby, and we’re getting closer to that moment. Hooper is treading water, examining the shot glass-sized shark tooth he just pulled out of the wrecked hull, his flashlight edging back towards the jagged hole.

We (me and Lila) know that the head of Ben Gardner himself is about to float out of that hole, the electrical wiring of the optic nerve dangling horribly from the empty socket. Alexandra does not. She gobbles popcorn, transfixed, delighted to be out with the grownups. How well I remember my own scream at this exact moment, clutching my cousin’s hand as we leaned forward in the stalls of the Glasgow Odeon, peering through the skeins of blue cigarette smoke caught in the projector beam. (Many years later I will patiently explain to my children that you could smoke in cinemas in the 1970s and that it was our second attempt to see Jaws. The first had failed as the showing was full when we got to the front of the queue. I will be asked, “Why didn’t you book online, Dad?”)

I can also recall my eldest son’s howl of disbelief when he first saw the head appear, some 30 years after I did, when he was 13. And then Lila’s just a few years ago. Alexandra clutches my hand in the dark. I look around the cinema. No packed house tonight. In stark contrast to the Glasgow Odeon in 1976, there is just one other person in here with us: a middle-aged lady who I suspect might be struggling with some mental health issues. Soon enough, by the time the Orca is setting out to sea (“Farewell and adieu to you fair Spanish ladies...”), she will be fast asleep, bless her.

Hooper gets closer to the jagged wooden hole. I have a split second to make the decision. I have to do it. Daddy Rules. Just before the atrocity floats out, I cover Alexandra’s eyes.

Come on, man – she’s only seven. (And the same went for the moment when the blood fountains out of Quint’s mouth.)

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Daddy Rules is a system we’ve developed over the years that allows the kids to watch movies that are borderline age appropriate by having the most challenging moments edited out manually by me in real time. It’s a fine system that enabled Lila to watch all of Tarantino by her 13th birthday, although by then I’d often have to chase her around the room and wrestle her to the floor in order to enforce the ruling. The nonsense serves a serious purpose: getting the kids eager to watch (and then rewatch) movies. By the time they were into their teens, many of Lila’s friends simply couldn’t cope with long-form narratives. When we hosted a movie night a few years back, some of her pals were stunned that their phones had to be surrendered before the film started.

More recently, I was asked to give a talk about working in “the creative arts” to about 50 fifth and sixth formers at a secondary school in Scotland, where I was introduced as “a novelist and screenwriter”.

“How many of you read novels?” I asked. “I mean, for pleasure, outside of school work.” Not a single hand went up. “Uh, OK,” I stumbled on. “You watch films though, right?” There wasn’t much of a response to this either. “Come on. How many of you watch films?” Maybe three or four hands went up. “But ... what do they watch?” I asked the (blushing) headteacher afterwards.

“TikTok,” he replied. “YouTube clips.” Woah.

At the risk of sounding like Colonel F Worthy Chops DSO (Retired), 14 The Terrace, Eastbourne, what in the name of Christ’s teats is going on with this bastard world? What’s at the end of the road of raising a generation who cannot cope with a piece of narrative longer than three minutes? Longer than a TikTok clip of someone lighting a fart?

One of the things that will go, it would seem to me, is empathy. When you immerse yourself in a novel – or a two-hour movie – you slip inside the skin of other people. (Lila, appearing in the kitchen doorway, heartbroken for Brody.) And without empathy, you’re fast into the world we saw represented in Adolescence. The other thing at the end of that road will be the end of the communal movie experience. If you raise a generation who no longer know or care about movies, then eventually you’re finding yourself in a cinema where the only other occupant is a semi-insane bag lady.

As the end credits roll, she comes up to us, blinking and yawning. “I fell asleep!” she says cheerfully. “What happened?” Yes, we have managed to find the only middle-aged person outside certain Amazonian tribes who has failed to see Jaws by 2025.

“Oh, nothing much,” I say. “The shark ate everyone.”

Perfectly satisfied with this climax, she toddles off.