In my youth, I loved Jules Verne. He was a writer whose work captured and sparked my imagination and kept me company in an otherwise lonely childhood.

The French novelist, poet and playwright was born in 1828 and is still one of the most translated authors in the world: he is regarded by many as “the father of science fiction”. Among his most famous works are, as you will know, Around the World in 80 Days, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Journey to the Centre of the Earth.

Many themes that Verne dealt with in his fiction – things that were regarded as simply impossible at the time – became reality later on, and with such precision that some people call him “the writer who invented the future”. He imagined submarines, TV news, glass skyscrapers, weapons of mass destruction, high-speed trains, cars with combustion engines and something eerily similar to the internet – machines that could communicate with each other. He even predicted electronic music.

Yet there is one book by Verne which remained unknown for a long while. Paris in the Twentieth Century was written in 1863. It is a dystopian novel imagining what France – if not the world at large – might look like a century into the future: he imagined a time dominated by business, technology, finance and commerce. His protagonist, a poet who has studied literature at university, is mocked by those around him because his skills are considered “useless” in this cold and cut-throat world.

Verne received a harsh rejection letter from his publisher. The story was too pessimistic, unrealistic too. It would take more than a century for this manuscript to see the light of the day, after his great-grandson discovered it in a safe.

Now Verne was spot-on about many things. But there is one issue where I believe he was wrong and time has proved him wrong – at least so far. Writing in the 1800s, he maintained that in the next 50 to 100 years the novel as a genre would be dead because fiction could not survive in the age of newspapers. Fiction demanded slowing down, news pure speed. How could the long-form narrative remain alive in an age of fast consumption? Strange how that argument sounds familiar here in the 21st century.

In the words of Mark Twain, history does not repeat itself but it often rhymes. We have all heard about “the death of the novel”. We have read claims that the long-form narrative was bound to wither away. Almost always this assertion was based on Verne’s rationale.

Gustave Dore's illustration of a ship sailing up into the air for Jules Verne's novel From The Earth To The Moon

Yet when we look at the data across the decades, reading fiction has been a steady habit. This is not solely a western phenomenon. The latest numbers shared at the Frankfurt book fair revealed that in 2025 there was close to a 30% increase in fiction sales in India. And books are shared, passed from hand to hand – sometimes a single copy can be read by five or six people.

Related articles:

I am not claiming everybody is reading novels – sadly not. Reading habits have declined worldwide, including here in the UK, as demonstrated by a recent YouGov poll, which found that 40% of the population had not read a book in the last 12 months. Nor do I deny the challenges presented by social media. Yet the faster our world spins, the deeper our need to slow down.

The art of storytelling is ancient and universal. You cannot rush it. You cannot be rushed by it. The ancient Greeks were wise in reminding us there are two ways of measuring time: chronos, which is the ticking time of mechanical clocks; and kairos, deep time, focused on depth, flow, meaning.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Literature lives and breathes in kairos, not in chronos. It speaks to our need for meaning and connection, which is as essential as our need for bread, air and water. This is why the National Year of Reading campaign, which aims to help people discover or rediscover the joy of books, is so important.

It is wrong to reduce a holistic university education and experience into a suffocatingly narrow tunnel with one goal: to make money

It is wrong to reduce a holistic university education and experience into a suffocatingly narrow tunnel with one goal: to make money

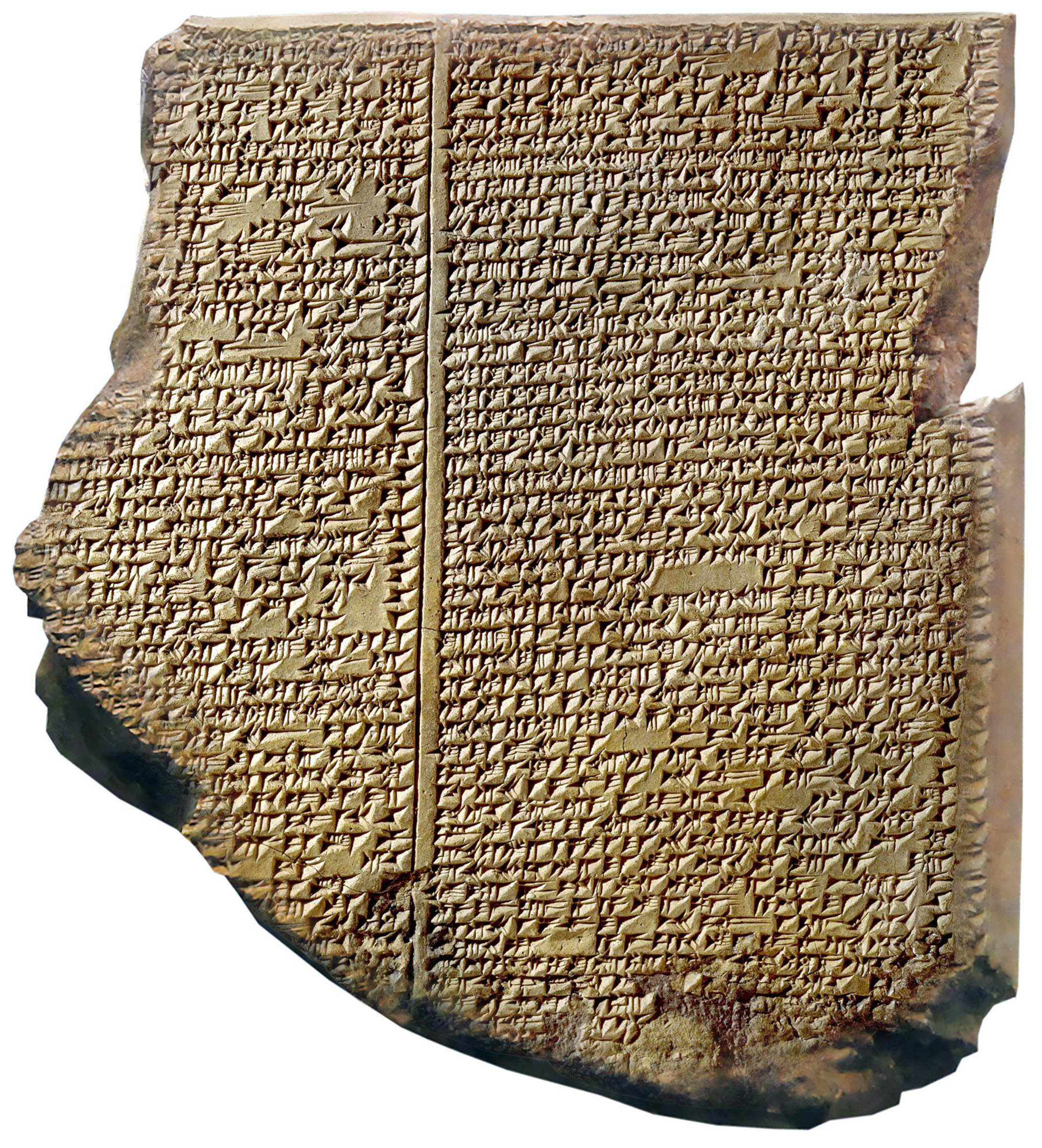

One of the earliest surviving pieces of literature is the Epic of Gilgamesh. Set down nearly 4,000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia, this odyssey continues to touch our hearts. Ever since Gilgamesh was narrated and then written down, so many mighty empires have come and gone, but a poem made of breath and of words has survived.

There is a reason why this theme is deeply relevant to us today. Because just like the novel has been declared dead in the past, the humanities are being declared dead right now. We are being told there should be fewer students, fewer scholars, fewer scholarships in these passé areas. Instead young people should be encouraged towards “high-income disciples”.

Although figures vary, the humanities are inarguably in decline; a study by Yale showed a more than 50% decline in arts and humanities majors between 2002 and 2022. In the UK, only 38% of students took a humanities course in 2021/22, down from nearly 60% between 2003/4 and 2015/16. Disciplines that bring in more revenue are regarded with more esteem. Again, here in the UK we have seen politicians proposing that the entire higher education system should be restructured and degrees that do not bring in any money should be “re-evaluated”.

It is fundamental that every student be able to find a good and decent job, and we need to stress the importance of Stem fields – science, technology, engineering and maths. But it is wrong to reduce a holistic university education and experience into a suffocatingly narrow tunnel with one goal: to make money.

Cutting off funding for culture and knowledge has social and political consequences. If you want a healthy and harmonious civil society, invest in the humanities and the arts, for they foster understanding, knowledge and empathy.

Empathy does not mean sympathy. It definitely does not mean pity. I much prefer the Germanic root of the word, einfühlung, which means “feeling into”. In our daily lives, rushing from one appointment to another, we rarely have the time or the motivation to think about our fellow human beings and what they might be going through. But when we read a novel, at least for a few hours, a few days, we feel into someone else’s existence.

A Neo-Assyrian clay tablet from the 7th century BC inscribed with part of the Epic of Gilgamesh

Countries like my motherland Türkiye have shown us that for a democracy to exist the ballot box in itself is not enough. Elections are important and we must encourage people to vote. But in addition to the ballot box, you need democratic institutions and norms, the rule of law, separation of powers, diverse and free media, diverse and independent academia, women’s rights, minority rights, and you also need an active, strong civil society.

When I was writing There Are Rivers in the Sky, I focused on the journey of a single drop of water. Today out of the 10 most water-stressed nations in the world, seven are in the Middle East and North Africa. Our rivers are drying up. Our rivers are dying. In traditional societies women are usually water carriers. They bring water to their communities and their families. When there is no drinkable water nearby, the distance a young woman has to cross increases, increasing the threat of gender violence.

In our minds we tend to put the most pressing issues of our times in separate boxes: “climate crisis” we keep in one drawer, “water scarcity” in another, “women’s rights” we place in another category and “racial inequality” in yet another. But in reality everything and everyone is interconnected.

Jules Verne’s father was a very successful lawyer. He wanted his son to be a lawyer and sent him to law school, where he was, to put it mildly, miserable. He tried to run away, even considering becoming a cabin boy in a ship, and when his plan was discovered by his shocked parents, he had to promise them that he would only travel in his imagination.

This might just be an apocryphal tale but it holds a kernel of truth. If a child is interested in law, maths or computers, encourage them in that direction. But if a child is an artist, or loves history or philosophy or poetry, do not force that young person into law or finance just because you think it is more “lucrative” or “prestigious”.

Finally, there is a quote often attributed to Verne that involves these beautiful words: “I dream with my eyes open.” I like this phrase. I like how it combines two separate components. On the one hand, it opens up space for imagination, creativity. On the other hand, for awareness, knowledge, research, observation, critical thinking. So as to be able to live our lives to the fullest, we need both.

Only the humanities and the arts are capable of blending these two. Only with their help can we continue to dream with our eyes open.

Elif Shafak delivered the 2026 National Humanities Lecture on 3 February at Senate House, University of London. This is a shortened version of that talk. The annual National Humanities Lecture is organised by the School of Advanced Study which celebrates the vital role of the humanities in public life

Photograph by David Levenson/Getty Images, Hulton Archive/Getty Images