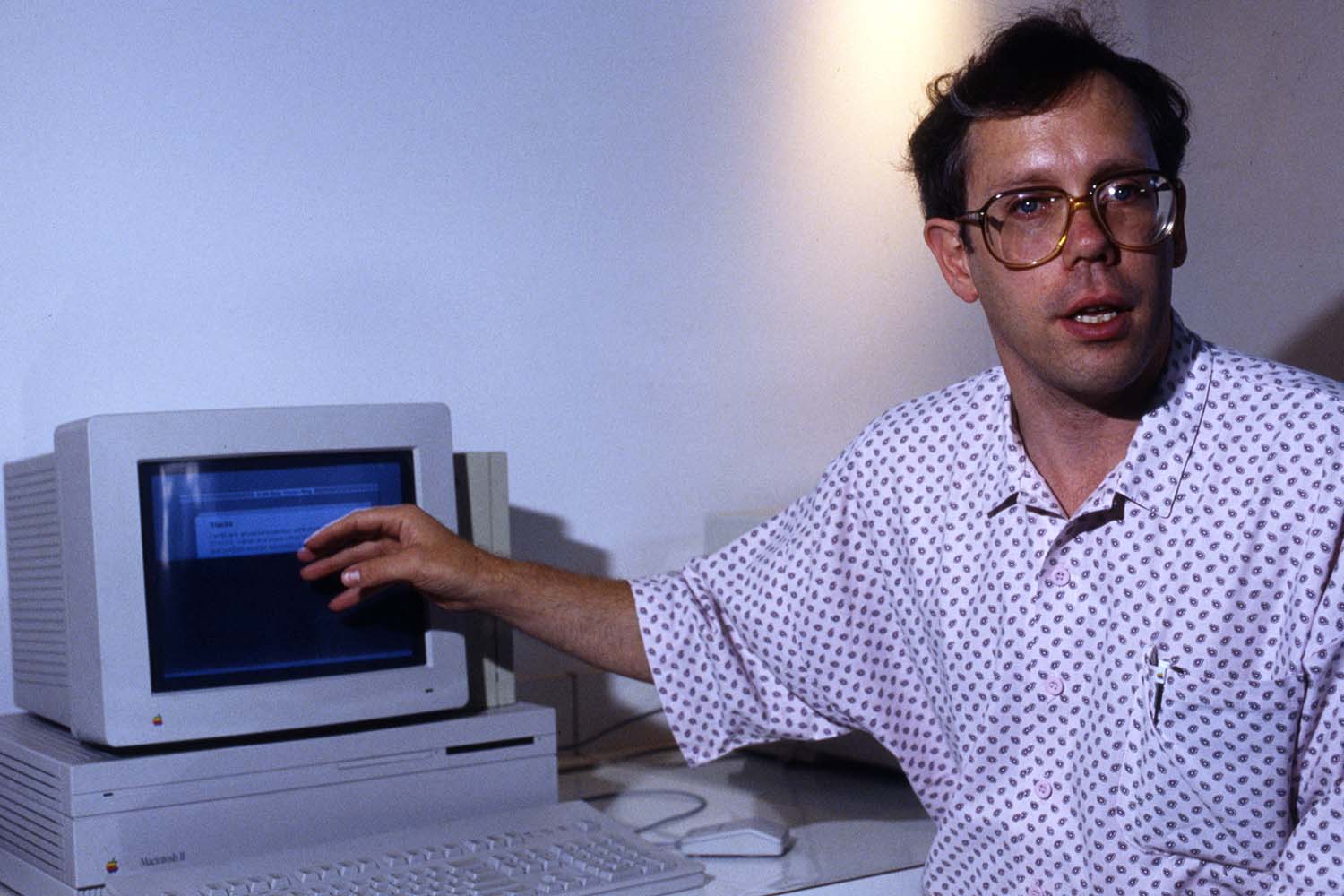

Bill Atkinson, one of the great software wizards of our time, has died at the age of 74. That probably won’t mean anything to most people, but it’s worth noting because he changed the way we all interact with computers.

I still remember the moment when I first encountered his work – a moment that James Joyce might have described as an epiphany. It was at a workshop for academics in Cambridge organised by Apple UK in 1984 to introduce its new Macintosh computer. In a stuffy conference room were a number of tables on which sat chic, cream-coloured machines with 9in screens and separate keyboards. Each had been set up displaying a picture of a fish, and I remember staring at the image, marvelling at the way the scales and fins seemed as clear as if they had been etched on the screen.

Picking up courage, I clicked on the “lasso” tool and selected a fin with it. The lasso suddenly began to shimmer. I held down the mouse button and moved the rodent gently. The fin began to move across the screen! I pulled down the edit menu and clicked on “cut”. The fin disappeared. Finally, I closed the file and then reloaded it from the disk.

As the edited image reappeared, I had the kind of feeling that Douglas Adams had experienced when he had done the same operation – “that kind of roaring, tingling, floating sensation”, as he put it when talking to US tech journalist Steven Levy. In the blink of an eye, all the Teletypes and dumb terminals and character-based displays that had been defining parts of my experience with computers were consigned to history. I had suddenly seen the point – and the potential – of computer graphics.

The program I had been using was MacPaint, and it was Atkinson’s creation, along with QuickDraw and several other critical elements of the Macintosh user interface. In an era when writing software was an art as well as a craft, he became a celebrated figure in Silicon Valley. “Looking at his code was like looking at the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,” said Steve Perlman, who, as a young Apple hardware engineer, took advantage of Atkinson’s software to design the first colour Macintosh. “His code was remarkable. It is what made the Macintosh possible.”

In an early advert for the Mac, Atkinson said that he thought of himself as “a cross between an artist and an inventor, but the medium that I use to do my art with is this programming stuff that’s like modelling clay. When I make changes to a program, I try to create something, and then I have to try it out on people.

“Oftentimes, some of the things that I think are very intuitive end up being difficult for people to understand and I have to go back and work with the medium more.”

MacPaint went through 12 big rewrites before he was satisfied.

For him, “having a rapport with the user” was the key thing.

After Macintosh, Atkinson and fellow software engineer Andy Hertzfeld – along with another Apple worker, Marc Porat – set up a company called General Magic to create what they called the “Magic Slate”, a device with a high-resolution screen that weighed less than half a kilogram and could be controlled by a stylus and swipes on a touchscreen. It didn’t work, largely because the necessary hardware hadn’t yet been invented. But with the 20/20 vision of hindsight, it looks as though what they were doing was “designing the iPad 25 years early”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

So General Magic failed and Atkinson became deeply depressed for a while. But, as Levy told it: “One night, he took LSD and wandered out of his home in the Los Gatos hills [in the San Francisco Bay Area]. Staring into the vast collections of pixels that made up the night sky, he became re-energised and decided to adopt some of the Magic Slate ideas into software that could run on the Mac.”

The result was the HyperCard, a program for the Macintosh released in 1987 that enabled users to build their own “stacks” of virtual notecards. Each card could have text and images, plus buttons that could be activated to do things: go to another card, say, or play a sound, or even run a script. The HyperCard was one of the most original pieces of software to emerge in the 1980s because it enabled ordinary users to create interactive content without having to master a complex programming language. In that sense, it enabled the “vibe coding” of its era.

So, in a way, you could say that HyperCard stacks were a forerunner of the internet. Except that Atkinson’s ran on a dinky personal computer, whereas Berners-Lee’s needed a global network to do its stuff. So let us raise a glass to dear old Bill. May he rest in peace.

What I’m reading

Split personalities

The End of Silicon Politics sees Yascha Mounk reflecting on the lessons of the Donald Trump–Elon Musk divorce.

The killing skies

An astonishing insight by CJ Chivers into how drones are reshaping warfare can be found in How Suicide Drones Transformed the Front Lines in Ukraine.

Fit for a Prince

Machiavelli and the Emergence of the Private Study is an intriguing essay by Andrew Hui.

Photograph by Gammo-Rapho/Getty