My son is anxious before school this morning. This is common – getting him out the door has always been a battle. In fact, it’s an ordeal, and one that has not lessened the whole time he’s been enrolled. Despite generally enjoying school, he resents the constant need to attend and will do anything to delay leaving the house for the short trip across the road that comprises his commute. This morning, however, he is anxious for another reason. He needs to see his friend George.

“I need to talk to him,” he tells me, between pensive bites of cereal. This is fairly standard, since George is one of his best friends, and a very cool guy who we all like very much. They trade tips about their Minecraft builds and devour the same comics and books. They sit together in school, and share swimming lessons every Monday evening. But my son’s urgency this morning is of a different order, because George has a Gengar. “It’s a poison-type Pokémon,” my son tells me, “and George has a spare. He told me.”

My son says these words while fanning out his own collection of Pokémon cards on the kitchen table, counting them assiduously. He speaks with a gravity that would be more appropriate if he and George were planning a heist and weren’t sure if they could arrange a wheelman in time. This is because my son, George, and every child in their class has been hit by a tidal wave of Pokémon addiction.

I was there for the first wave, when Pokémon first broke containment from its native Japan and became a global sensation in the late 90s. I was just too old to be properly afflicted but, even so, it was unavoidable. As my son began devouring the earliest seasons of the tie-in show on Netflix, my wife and I both realised we’d watched much of it at the time.

Had I not aged out so quickly, I’m sure I would have shared my son’s addiction, since Pokémon is best understood as a hyper-powered version of the Panini sticker albums I adored when I was his age, albeit with the wondrous addition of martial combat. Imagine, if you will, a world in which you jostle in the playground for swaps of players to add to your Premier League 1996 annual, but with the added excitement that your Phil Babb can fight their Warren Barton with fire blasts and psychic shockwaves.

I try to impress him with my own knowledge of the oeuvre, but my 30-year head start falls by the wayside

I try to impress him with my own knowledge of the oeuvre, but my 30-year head start falls by the wayside

Training and battling your characters is, ostensibly, the point of the myriad games, shows and books related to the series. But the actual joy at its core is the collecting in and of itself, a truth best evidenced by the ubiquitous and charmingly mercenary, catchphrase: “Gotta Catch ’Em All!”

It’s this recipe for conspicuous consumption that has made Pokémon the most valuable media franchise ever created, earning $99bn across all its various properties. That’s more than the collected earnings of all media – films, shows, books, games and toys – relating to Star Wars, Star Trek and Harry Potter combined.

My son can never run out of characters to obsess over. There are some 1,025 different Pokémon species, and too many media entities have sprung from it to count. I do not mean that rhetorically. There are so many offshoots, adaptations, cross-overs and side-ventures that getting a stable number of Pokémon properties is impossible. No two sites give you the same figures, and Pokémon’s various Wikipedia pages are longer than those of the Napoleonic wars. There is even a Wikipedia page named “Lists About Pokémon”, dedicated solely to cataloguing 25 ancillary pages listing every conceivable type of creature, game, card and anime in the series. BBC iPlayer hosts six distinct runs of Pokémon TV shows, encompassing more than 600 episodes. So many, in fact, that they have a dedicated Pokémon channel that broadcasts an infinite loop of their adventures.

It is, to be honest, the perfect thing for a six-year-old boy to obsess over. Simple in its presentation, labyrinthine in its dimensions, Pokémon is a near totally harmless funnel of content through which to force his every nerdy impulse; a repository for every child’s passion for indexing thousands of completely useless datapoints. It’s also highly social. Like football stickers before them, collecting Pokémon cards involves a busy and active life of day trading, negotiation and one-upmanship. Thankfully, he has not yet begun begging us to buy him the full-fat range of cards at eye-watering price-points, since he and his friends are content, for now, with the varieties given out in Happy Meals, or bought cheaply in bulk from online retailers.

I try to impress him with my own knowledge of the oeuvre, but already find my 30-year head start falling by the wayside. He routinely asks me my favourite Pokémon, and when I rattle off heavy hitters like Charizard, Bulbasaur or Mewtwo, I’m informed that these basic picks mark me as a novice.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Rattled, I tell him his own collection is quite bare. “You need a Gengar,” I say, with something like spite. “Yeah,” I repeat thoughtfully, “a Gengar would really help.” He puts on his shoes, grabs his water bottle and stands by the door. This is miraculous, since it is a full 10 minutes before school is due to start.

“I need to speak with George,” he says.

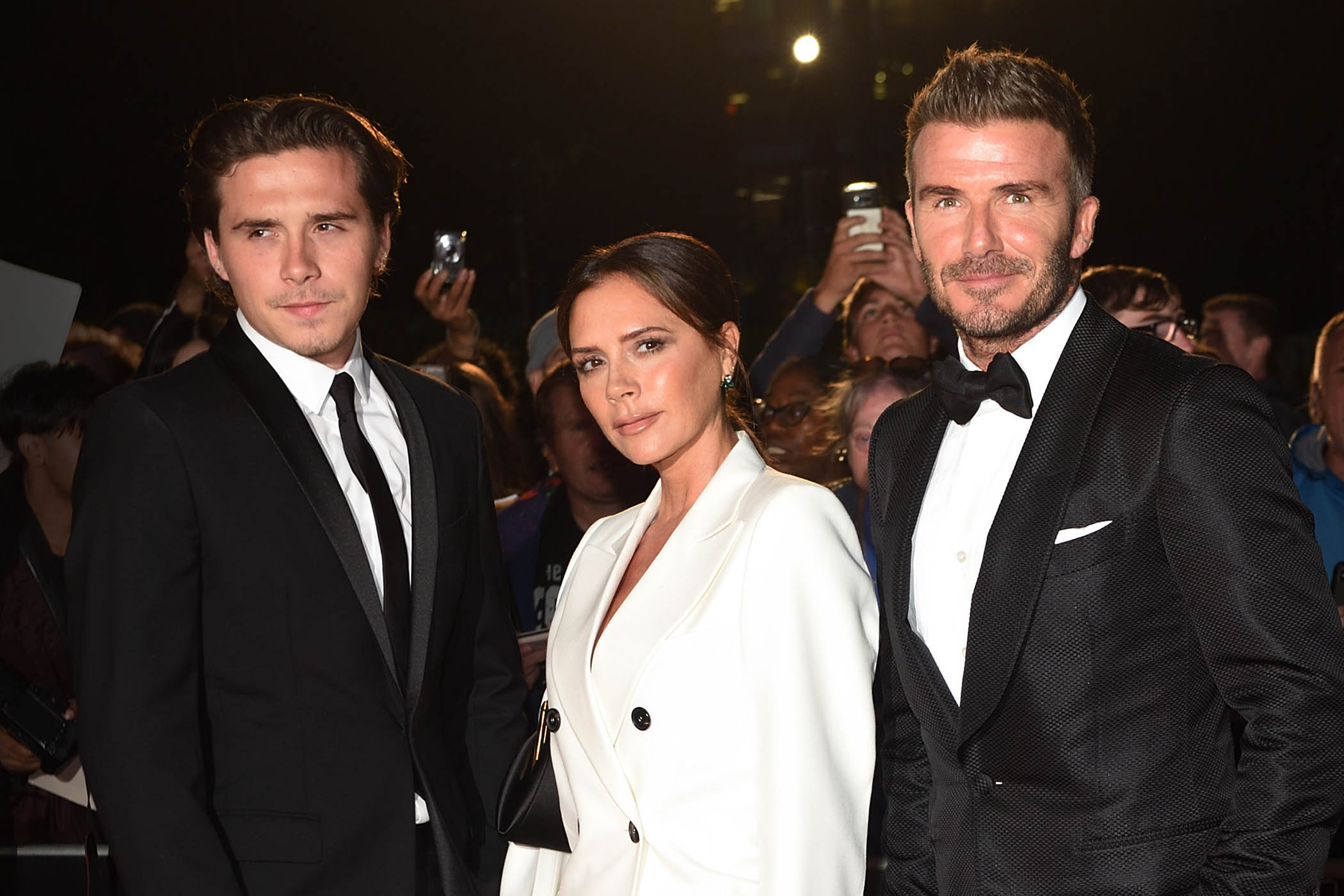

Photograph by John Keeble/Getty Images