Compare and contrast these words from two American presidents. “Our alliance is the foundation of global security. Our trade and our commerce is the engine of our global economy. Our values call upon us to care about the lives of people we will never meet. When Europe and America lead with our hopes instead of our fears, we do things that no other nations can do, no other nations will do.”

“Europe is not doing a good job in many ways … I know the smart [leaders in Europe]. I know the stupid ones … They talk too much and they’re not producing … And if it keeps going the way it’s going … many of those countries will not be viable countries any longer … Most European nations, they’re decaying … I think they’re weak.”

The first is Barack Obama, speaking in Berlin on 19 June 2013. The second includes excerpts from a Donald Trump interview with Dasha Burns of Politico on 8 December 2025. Quite a contrast, is it not? And the new American national security strategy – published on 4 December 2025, welcomed in Moscow and the prompt for the Politico interview – throws fuel on the fire, asserting that Europe’s “economic decline is eclipsed by the real and more stark prospect of civilisational erasure”. So what is going on?

The reality is that Trump has been criticising Europe for decades for “ripping off America” – all the way back to letters he wrote to US newspapers in the 1980s. And he has intensified his attacks since launching his political career. In his 2016 election campaign, he described called Nato as a scam through which Europeans got America to pay for their defence while spending their budgets on social policies. In 2017, he reportedly presented Angela Merkel with an invoice for more than $300bn for decades of US military spending on the defence of Germany (the White House denied the story). In 2018, he told CBS the EU was “a foe” because “in a trade sense they’ve really taken advantage of us”. And in 2020, he told Ursula von der Leyen at Davos that Nato was dead and the US would leave.

So these are actually familiar tunes in new arrangements – if they sound novel it’s because you haven’t been paying attention. And Trump has a point on Europe’s chronic failure to spend enough on defence: we have been lunching for free at the US table for decades, and it was bound to end. But Trump’s words also remind us of a fundamental truth about him: he simply does not buy the judgment that has guided post-second world war US foreign policy – that the US has a strategic national interest in maintaining a secure, prosperous and democratic Europe. For Trump, the world revolves around the Big Three of America, China and Russia. Europe just doesn’t cut it.

And there is another theme running through both the security strategy and the Trump interview that merits some analysis. Trump is evidently deeply frustrated with the European position on Ukraine. The security strategy accuses European officials of holding “unrealistic expectations for the war perched in unstable minority governments, many of which trample on basic principles of democracy to suppress opposition”. Meanwhile, it is almost entirely uncritical of Russia.

Why is Trump so indifferent to the rights and wrongs of this issue; to the glaring reality that one country was the unprovoked aggressor, the other the innocent victim? There are plenty of lurid theories in circulation about this apparent blind spot. But the most persuasive explanation I’ve heard came in a private conversation with a senior military adviser to the president. Trump knows that Russia has the world’s largest proven natural gas reserves, is the third largest oil supplier and has 10% of the world’s rare earth reserves, though it actually processes and sells less than 1%, so ill-equipped are the Russians with the necessary technology. Trump sees an opportunity for a huge trade deal with Russia, cutting US companies into the energy and rare earth opportunities. And Ukraine is an obstacle on the road to achieving this deal. The Trump approach is therefore either to persuade Ukraine to move or drive around it. As Michael Corleone said to his brother in The Godfather: “It’s not personal, Sonny. It’s strictly business.”

Europe will have to learn to look after itself. Support from the US will diminish

Europe will have to learn to look after itself. Support from the US will diminish

So where does all of this leave the UK and Europe? I’d draw three conclusions from recent developments.

Related articles:

First, it is at least possible, and arguably likely, that Trump will abandon his Ukraine peace efforts at some point in the next few months and walk away, including from intelligence cooperation and further arms supplies to Ukraine. I hear that Europe will struggle to backfill on either count. If Russia can break through the heavily fortified Ukrainian defensive lines in the Donbas, the road to Kyiv will be open. European countries should be planning together now on how they can give the maximum possible support to the defence of Ukraine and what this means in terms of expanding European weapons production. In particular, it is crucial that next week’s European Council in Brussels overcomes Belgian objections and authorises the loan to Ukraine of the €90bn (£79bn) worth of frozen Russian assets currently sitting in a Belgian bank.

Second, the message from across the Atlantic encapsulated in the US national security strategy is clear: Europe is going to have to learn to look after itself. Support from the US will diminish and become less guaranteed as its focus shifts to the western hemisphere and the Asia-Pacific. Mark Rutte, Nato secretary general, may have been overoptimistic in asserting last Thursday that the US remained fully committed to Europe. But he was absolutely right to call for Europe collectively to step up, and to highlight Germany’s commitment to reach 3.5% of GDP defence spending by 2029 as a model others should follow. There is a lesson here for the UK and the Starmer government: we have a commendable record under governments of both persuasions on support for Ukraine and Nato, but our plans on meeting the new 3.5% target are far too backloaded.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

And third, it cannot be assumed that, come 2029, Trump’s successor will return the US to a more traditional foreign policy path. I think some elements of Trumpism may continue whether Republicans or Democrats win the White House next time round – among them some of Trump’s tariffs, the pressure on Europe to take greater responsibility for its own defence, and the harder-edged pursuit of US national interests embodied in America First. Europe needs to recognise that the world has changed, probably permanently, and start to prepare for a world order that is based on power rather than rules. And the UK, currently dangerously exposed to global currents as a medium-sized economy floating uneasily mid-Atlantic, needs to get closer to the EU much faster and more comprehensively than the government’s modest reset allows.

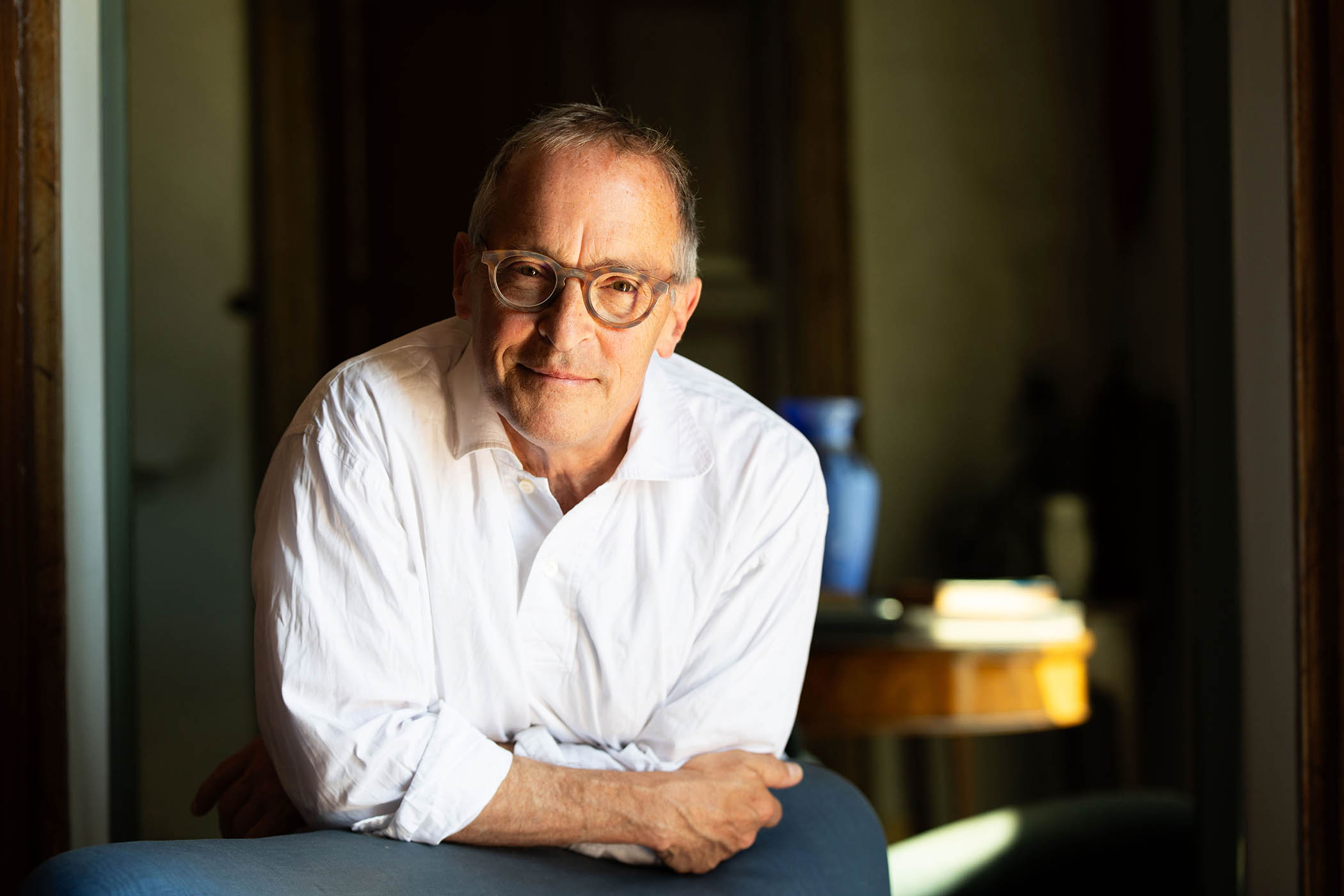

Kim Darroch was British ambassador to the US from 2016 to 2019, and is author of Collateral Damage: Britain, America and Europe in the Age of Trump

Photograph by Ludovic Marin/AFP/Getty Images