Photographs by Neil Bedford

I was still a boy when I arrived at Crystal Palace at 15, having just been released by Southampton. I still have the rejection letter at home. A psychologist would probably sit me down on the couch and tell me it’s time to let that go, after 40 years, but it remains an important anchor for me. That moment tested the faith I had in myself. Thankfully, at Palace, I met someone who believed in me and who would change the course of my life: Alan Smith, then youth coach, who went on to manage Palace in the top flight. Tough, honest but thoughtful and supportive. Alan saw something in me. He guided me, challenged me, encouraged me. He understood the world I was stepping into in a way my loving parents, for all their support, simply couldn’t. From the start, he was more than a coach. He was a mentor, and still is. Our relationship shaped my eight years in the England job, and continues to shape me today.

Being England’s manager is bigger than football. By default you become a coach for millions of men you will never meet. Yes, I had to win football matches, and every minute of every day in the role I was thinking about, and working towards, that goal. But I always saw the job as something more: a position with purpose, a platform to support young men and to be, when possible, a mentor. It’s here that relationships matter – how you help people to grow and improve, both on and off the pitch.

While I care equally and deeply about young women, there has been a lot of debate recently about young men and how much they are falling behind. As someone who has spent their life in the company of young men, as a player and coach, I feel able to speak about their challenges. I’ve experienced them myself, and have seen first hand the importance of male role models. 2.5 million boys in the UK are growing up without a father figure at home. Boys are more likely to own a smartphone than live with their dad. There is more than an absence of male mentorship, there is a vacuum.

Despite the incredible work that mums do raising boys, when they go looking for guidance beyond the home, as I did when I was 15, they often land on so-called mentors in the virtual world: influencers, algorithms, echo chambers. They stumble upon voices that preach dominance over empathy. Figures who suggest that real men don’t cry, don’t care, don’t ask for help. That success is about control, money and power. And as boys’ brains are still developing their critical thinking still forming, they become vulnerable to these messages. Once they start to look, the algorithm continues to throw the same things towards them, getting more extreme over time. We’ve seen what happens when this influence takes hold and becomes too much: withdrawal, anger, violence, loneliness. These are not the role models our young men need. Young women and mums I speak to overwhelmingly agree.

The penalty miss of 1996: Southgate is consoled by manager Terry Venables after England go out to Germany

Although I’ve stepped down from the England job, I still feel this urge, a sense of duty, to give back, and help young people. The question I ask myself is, how? I’ve spent time listening – to teachers, youth workers, academics, and prison staff. Visiting schools, community centres, detention centres. I know I don’t have all the answers to the complex challenges young people face today, but I am curious to learn more. What I do know, from my life in football, is that you need the right people around you to succeed. Football has some wonderful people, coaches and mentors, all over the country and at all levels, guiding young players through the ups and downs of the game. These relationships are so powerful. I am sure that in a society where strong role models are more and more scarce, the same principle applies for all young people. It can make the world of difference, just as Alan did for me.

On and off the pitch, Alan pushed me. He didn’t avoid difficult conversations or sugar-coat things to stay popular. When my standards slipped, he let me know. It’s incredibly difficult to “make it” as a professional footballer, and I struggled adapting to football being my job from it being something I did for fun. I know that at times I didn’t always fit the mould of a professional player. Some people used to think I was too nice, too quiet. Others questioned whether I wanted it enough. I remember Alan telling me once, as I came off the pitch exhausted with a 6in gash to my leg, that I was too soft to make the step up. The game then was not as it is now. Some of the tackles (and tactics) were miles away from the precision football played today on Premier League pitches. I hated him for that, but it made me more determined, and I found that inner strength and resilience to keep going.

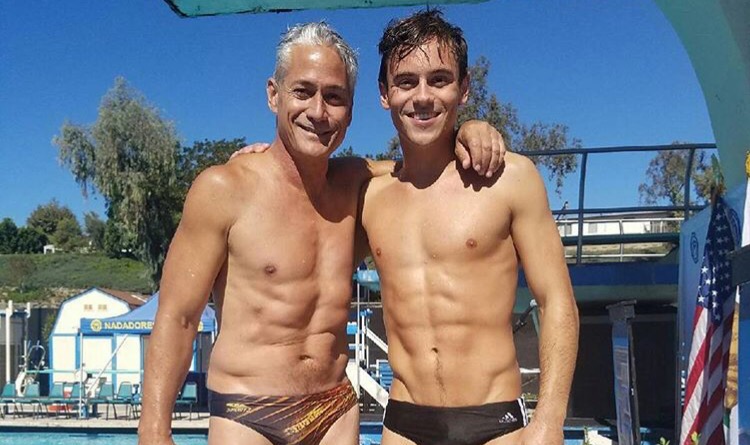

It's how we do things around here: with mentor and friend Alan Smith

I came to see that Alan’s guidance wasn’t about criticism, it was about helping me grow. He made me realise that to succeed, I didn’t need to change who I was. I just needed to believe in myself. That belief, that inner strength, didn’t arrive overnight, but Alan planted the seeds.

Related articles:

What Alan did was also bigger than football. As an apprentice, you have very little time to spare in a structured day: you’re in early to put the kit out, you train, then you sweep the dressing rooms. But when I turned pro I had far more free time. Alan ensured I filled it productively. He had a background in commercial property, and would have me measuring up shops, helping to do rent reviews, looking through documents. It taught me some valuable life lessons. Looking back, I realise Alan was thinking about my future. Most of all, he instilled in me a set of values: hard work, humility, accountability, the importance of giving back to the community. Those values have stayed with me through everything I’ve done since.

When I began my coaching career at Middlesbrough in 2006, I thought winning was enough. That it was my only measure of success. By the time I took over England Under-21s in 2013, I’d changed. I realised football coaching was just one part of my role. These young men needed something else: someone who believed in them, someone who listened, someone who could show them what was possible. I saw versions of myself in each of them. I remembered what it felt like to be unsure, to doubt, to think certain dreams were for other people. It was only at the age of 25 that I finally realised I might be good enough to play for England. Until then, I didn’t think it was possible. Me? A lad from a comprehensive in Crawley? I’d have laughed if someone had told me I’d one day manage the national team. So I made it my mission to build not just better players, but stronger people, too.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Building better people meant treating players as individuals, recognising each has a unique set of talents, their own personality and are in their own phase of life. A 19-year-old on his first call-up has different needs to a 32-year-old father of three. I wanted the players to feel valued for who they were, not just what they could do on the pitch. That meant building trust, consistency and encouraging vulnerability. People call it culture: a set of values and behaviours everyone experiences every day in their family, school, communities, workplace or sports team. To put it more simply: “It’s how we do things around here.”

Taking on Spain's Guilermo Amor on 22 June 1996

That had a ripple effect across the nation. We knew the world was watching us and that everything we did would be mimicked on Sunday league pitches and in school playgrounds: not just hairstyles and fashion choices, or how the squad performed during matches, but how the players carried themselves in the world. So we set expectations. Show up on time. Respect your teammates. React the right way to setbacks. And if those expectations weren’t met, we acted. Not to punish, but to guide: to show that standards matter, because they do.

I tried to live by these same standards myself; I felt a duty to lead in the right way. Not just as a coach but as a role model.

What I found was this: when you build that kind of environment – a place where people can speak, be heard, be honest, where standards are high, but support is higher, something powerful happens. People grow. They believe in themselves, not just as players but as people.

Belief is such a powerful yet fragile tool. One minute you can feel invincible, the next like you are going to fail. I remember stepping up to take that decisive penalty against Germany at the old Wembley in the semi-final of Euro 96. There were 90,000 people watching in the stands and millions more at home. With nerves and exhaustion setting in as I made the long walk to the penalty spot, and no clear routine or hours of practice to fall back on, doubts began to enter my mind. It was as much as I could do to hit the target. The keeper saves, they score the next one, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Contrast that lack of belief, in the moment, with another penalty shoot-out that I found myself in 22 years later, this time as manager. It was England v Colombia, the knockout stages of the World Cup in 2018, and it was another centre half, Eric Dier, who stepped up to take the decisive penalty. Even though England had lost all five of its previous penalty shoot-outs, and hadn’t won a knockout game for 10 years, I knew he was ready. He was practiced and prepared. As I stood on the sideline, my eyes following him on that long, lonely walk to the penalty spot, I believed in him. I believed he would score. Eric duly dispatched the penalty and helped us write a new chapter in English football history.

Over time, these players I believed in became leaders and mentors themselves. Harry Kane, John Stones, Jordan Henderson and others had all been with me for a long time. I’d watched them grow from young players facing knock backs and doubts, to towering professionals, with the utmost belief. I knew their families and their children, too. That trust, continuity and care they hopefully received, perhaps encouraged them to be mentors to others. So when Jude Bellingham buddied up with Jordan Henderson on his first camp, or Harry Kane welcomed new squad members with open arms, I knew we were setting the right tone.

But mentorship doesn’t just belong to football. It belongs to all of us. It can be as simple as a conversation, a quiet word, or a consistent presence. It can be found in classrooms, barbershops, kitchens, construction sites, youth centres, workplaces, community halls. It doesn’t need a job title or a salary. Just time and care, and a willingness to show up. That, to me, is at the heart of it. And the need for mentorship has never been greater. Social media bombards young people with unrealistic images and warped values. The economic world is uncertain. Technology is changing how we live, communicate and work. Young people are more connected than ever, yet more isolated. The pressures they face are unlike anything we’ve known.

I know it’s a complex problem, but I believe this can change: I know what a difference just one mentor can make. We need to flood the lives of boys in society with positive role models. Men who listen, who guide, who challenge and support. Men who show what it looks like to lead with empathy, to fail and recover, to grow and give back. It doesn’t take a title or a badge. You just need to care, to be present, to listen and to lead by example. There’s nothing more special to me than a player who I coached 10 or 15 years ago picking up the phone and asking for advice.

Since I started speaking about this, in public and private, countless people have approached me, wanting to help. They ask the same thing: what can I do? Where do I go? How do I get started? We need to make that pathway clear. There are brilliant mentoring schemes already, but too few know about them. Not enough young men access them. We need everyone: government, charities, communities and individuals to work together. To step up and to show the next generation what’s possible. If we don’t, the costs are stark: disengagement, underachievement, lives lived in the margins. Girls and women needlessly suffering from the attitudes of boys. We know the bleakest statistic of all: suicide remains the leading cause of death for men under 50.

Southgate with Bukayo Saka after his decisive miss in the penalty shootout gave Italy victory during the Euro 2020 final at Wembley Stadium in 2021

This summer, schools will close. Boys will have more time, more freedom, more exposure to influence. The question is, what kind of influence will they find? If you’re reading this and wondering what you could do – start by asking yourself: who helped me become the person I am today; could I be that person for someone else? I think about that a lot. What would have happened if Alan Smith hadn’t been there when I was 15? Where would I have gone, what voices would I have listened to? Whether I would have had the strength to make the right choices, I’ll never know.

We don’t always get to know how much of a difference we make, but I’m certain of this: showing up for a young person today might shape who they become for the rest of their life. It might stop a tragedy. It might spark a future. I know it did for me after that night at Wembley in 1996, when Stuart Pearce took me aside and told me how he felt after his penalty miss, also against Germany, in the World Cup in 1990. When Terry Venables said publicly, “What doesn’t destroy you will make you stronger.” When Alan, and many other mentors, believed in me, and steered me through.

Most young men will face their own penalty moment at some point in their lives. Maybe it’s a moment when they feel lost, or experience rejection, and they search for someone who cares. In that moment let’s help them find something worth holding on to, because even one voice, one relationship, has the power to change everything for them. I know it did for me.

Further reading: Game changers

Photographs by Alan Smith; Alamy; Getty