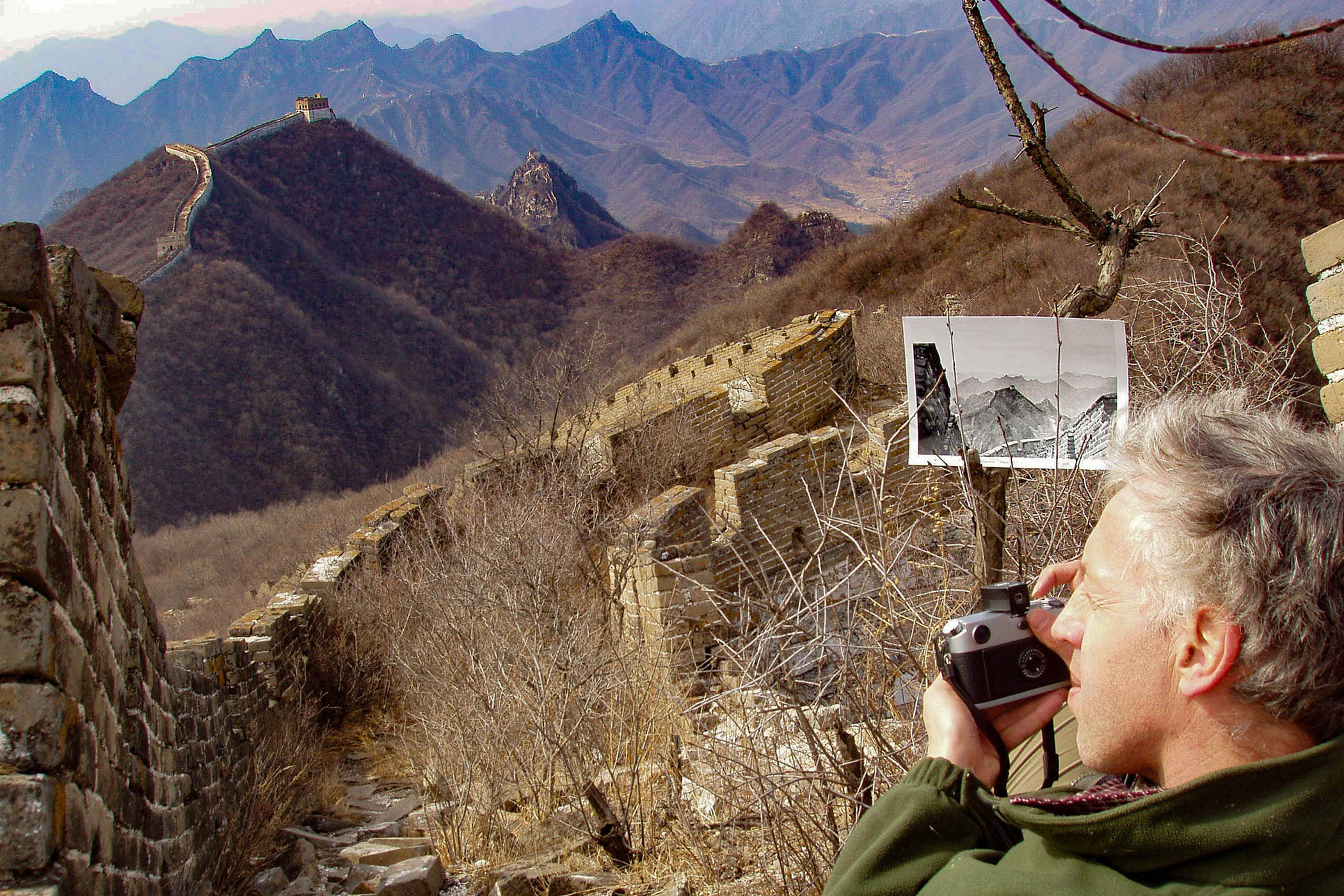

Photograph by Josiah Bania

I was 38 when cancer treatment killed most of my sexual nerves. After three years of bouncing between specialists, I learned the back pain I’d attributed to childbirth was, in fact, a tumour the size of a baseball on my sacrum. I had rare, aggressive bone cancer (so rare my doctors all pronounced it differently) and it had to be treated right away. Because the tumour sat nestled among the nerves at the base of my spine that control walking and continence, my medical team didn’t want to operate. They suggested a heavy dose of radiation to the pelvis.

“It will bring instant menopause. It may affect bowel and bladder, though not as much as surgery, and it could, down the line, affect sexual function,” repeated my male doctors. I never asked them what that meant (ability to orgasm, I vaguely assumed), but it was a side-effect that seemed trivial when stacked against the risks I was facing. Also, to keep afloat in what felt like a tidal wave of horror, I had a policy of only asking questions that would affect my decision-making. Sexual function, whatever it meant, wouldn’t change the plan. I signed the papers. I donned the purple gown. I kissed my husband goodbye in the waiting room.

Menopause came, with its hot flashes, hormone tsunamis and sudden urges to make out with unsuitable men. My husband met these changes as he had everything else in our 15-year relationship: with long-suffering good humour. He made cooling soups. He came to the follow-ups. He gave me his blessing to get whatever I needed out of my oversexed system. I was, to put it mildly, sexually functional, and I assumed I always would be.

A year later, at my daughter’s school fair, as I sat with kindergarteners making stuffed fairies, I realised I couldn’t feel my ass on the chair. I went to the bathroom and discovered I couldn’t feel much of anything. “The effects of radiation unfold over time,” my doctor told me. “The loss will be progressive.” (Which, like “rare” and “positive” is a word I used to like.) I lay on the table at pelvic-floor therapy, tears pooling in my ears, shaking my head to questions of “Now do you feel anything? What about now?”

I went to the bathroom and discovered I couldn’t feel much of anything…

I went to the bathroom and discovered I couldn’t feel much of anything…

My husband and I tried sex with my new body, though neither of us was emotionally prepared for what we found. Trying to make things seem normal, I felt like I was in a disembodied dream, going through motions, watching him react, with no sensation of my own. We started to avoid sex. Even if we were able to start, I’d be consumed by loss and dread and need to stop.

I’m looking at a lineup of slick plastic dicks spread out on a desk, “covered by insurance” according to the oncological sexologist. She rolls them toward me along with medical-grade lube. “Try them on your own,” she suggests. Homework for my slacker vagina. “With time, you may be able to get back some function. Rarely, nerves regrow. And in the meantime, practising with these can help you manage uncomfortable sensations during intercourse.” The implication being that I could come to tolerate sex enough to maintain some semblance of pre-cancer normalcy.

“The problem isn’t that I can’t tolerate it,” I say, “it’s that I don’t know how to have sex without feeling like…” I trail off and start to cry. As if by reflex, she hands me tissues, but all I want is for her to let me cry. I want to hear: this is hard, isn’t it? Her can-do attitude and list of exercises makes me feel like I’m failing even at this.

Cancer rehabilitation is focused on getting something back. Indeed, the word means to restore to a former state, to make fit again. “I’m not going to let it change me,” patients say defiantly. But what about those of us who are irrevocably changed? For whom the idea of rehabilitation is less of a dangling carrot and more of a taunt?

On my worst days, I focus on what’s lost, and that’s easy to do: a sure future (which was always an illusion), tens of thousands in out-of-pocket expenses, my fertility, energy, libido and nerve function. But on my best, I look at what’s been gained: compassion for people’s suffering, total clarity of priorities and a daily reminder to enjoy my life. I can grunt my way through Kegel exercises, cringe on the acupuncture table and diddle with dildos. None of it makes me feel sexy and it doesn’t bring me closer to myself. I resolve to approach this not as a question of regaining what’s been lost, but as an opportunity to grow towards something new.

I’m in a Zoom room with seven other women, ranging from late 20s to middle age. We sit, each in our little box, surrounded by coffee cups, children’s toys, papers. Some have turned their backgrounds into aspirational vacation spots – beaches or deciduous forests. Our Tantra coach (I’ll call her Celeste) is radiant, in her mid-60s, dialling in from her back porch in San Diego. We’re here to learn to reconnect with our bodies. Everyone has a story about where the rupture began. Many speak of sexual assault and bad relationships.

I realise how long it’s been since I was in a space where people speak about their struggles unrelated to illness. Cancer makes friends tread lightly when sharing their own problems. After detailing marriage troubles or work issues, they’re quick to add, “but it’s nothing like what you’re going through!” I think they do that out of deference, but it can feel lonely. It’s comforting to hear of other women’s sexual problems, even if ours are different; to be reminded of the complex interplay between psychic trauma and physical pain.

We start by breathing low into the pelvis and Celeste guides us through a visualisation. I wince when she asks us to picture our sacrum, “the sexual chakra,” knowing mine is covered in calcified cancer. But as I stay with the image, it neutralises. It reminds me of a sculpture I once saw of a beautiful white Buddha covered in barnacles, as if it had spent a decade meditating at the bottom of the sea. In my mind, my sacrum comes to look something like that.

I needed to work with my mind to find my way back to the erotic

I needed to work with my mind to find my way back to the erotic

She asks us to feel our skin move against our clothing as we breathe, a sensation I have never been aware of before. She prompts us to put our awareness into different parts of our bodies – the back of a hand, sole of a foot, top of a knee – to discover how much sensation is always there, pulsing beneath our conscious perception.

Then, she asks each of us to grab a wine glass. I watch the other women get up from their desks or couches and rummage around in kitchens across the country. We all meet back with stemware in hand. “Close your eyes. Start to touch the glass. But touch it for your own pleasure,” Celeste says. It was as if my hand had been waiting for that prompt its whole life. I had no idea there were so many nerves to fire there and they light up in response to the glass – the delicate rim, long stem, the cool bowl that fits perfectly in my palm.

“It’s the same with a partner,” she says. “It’s not about what you do to them, it’s about how much you allow yourself to feel in the process. Breathe deeply, touch for your own pleasure and everything changes.”

Over time, I practised these simple techniques (deep breathing, body awareness, touching for my own pleasure) by myself, outside of any sexual context. Eventually, I brought them to my husband, still outside of sex (a hand on a face, a massage). When we tried them in bed, there was still a lot I missed, but it was by far the most connected we had been since my treatment. Moreover, it put us both in a place of presence and curiosity.

I don’t fault the medical approach. Up to 90% of women experience some form of sexual dysfunction post-cancer treatment. Increasing numbers of those diagnosed are young adults and many of them (and their partners) may benefit from a physical approach that prioritises a feeling of normalcy. But I needed to work with my mind, breath and attention. I found my way back to the erotic by turning towards the unknown, opening to change and tuning into pleasure in unexpected places. Over time, as I strengthened the nerves I did have, orgasms came back.

Each morning, my husband kisses me goodbye before he leaves for work. On the best days, I take a deep breath and put awareness in my lips – all my awareness on the million sparkling nerves that still fire there. I kiss him back, for pleasure.

Amanda Quaid is the author of No Obvious Distress (John Murray, £14.99). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £13.49. Delivery charges may apply

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy