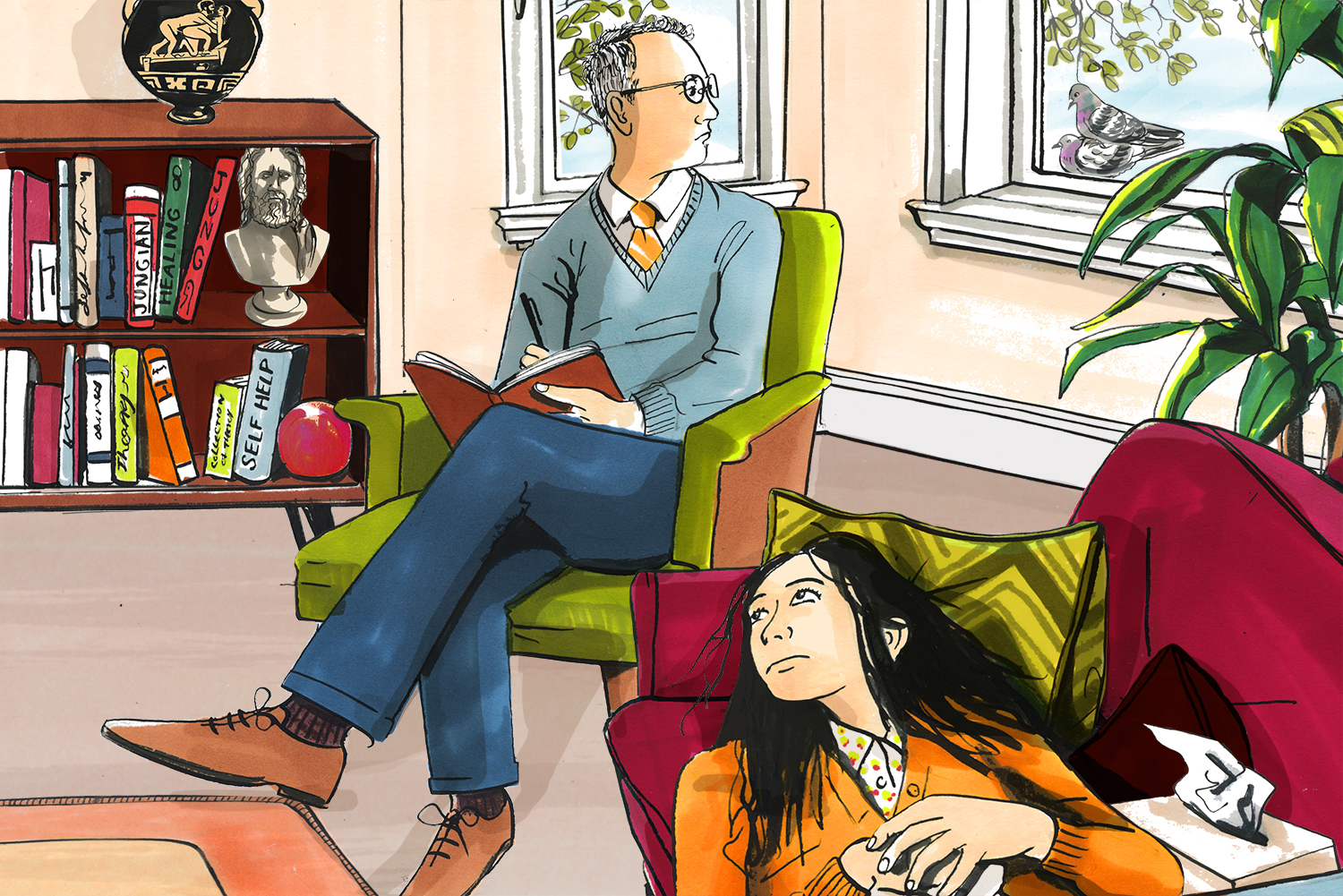

Illustration by Clare Mallison

Stewart was a 45-year-old divorced college English professor who told me on our first date that he wasn’t bothered by being short. I craved his confidence. I was dazzled by his record collection, the dreamcatcher above his waterbed, his knowledge of hip restaurants and, above all else, his ability to make me feel special. He read my poetry and literally lifted me up on to his kitchen counter to celebrate my talent.

Now that I’m in my 70s, Stewart doesn’t seem terribly old, but when we met I was 25 and back in school, and floating around looking for a port, so his place in the world seemed defined. Stewart had lived long enough to have amassed a house, a van with a built-in bed and tiny refrigerator (for trips to the beach), a wardrobe of Dylan-esque vests and man beads, and food rituals and preferences that fascinated me.

For example, Stewart exposed me to smaller, multi-grain slices of bread. To someone who had grown up on sliced white bread, canned vegetables and tomato ketchup on the table every night, Stewart’s food was Star Trek-exotic.

When Stewart and I met, the size-8 dresses of his previous woman were still hanging in the bedroom closet. She was on the way out. That I was being shuttled in hot on her heels somehow didn’t faze me. Even though he had confessed his struggle with needing women (there was a bevy of female students, advisees and ex-lovers who always seemed to be in orbit around him), I wasn’t worried. “Size 8” had been too conventional, he explained; I was bohemian, a talented poet. And, after all, hadn’t I come home one day to find he had arranged the colourful block magnets on the refrigerator to read “THE REAL THING HAS DONE COME ALONG AT LAST”? Stewart had those magnets because he was divorced, with children. That, too, seemed extremely adult.

I was dazzled by his record collection, the dreamcatcher above his waterbed, his knowledge of hip restaurants

I was dazzled by his record collection, the dreamcatcher above his waterbed, his knowledge of hip restaurants

But then there was that day I wandered into Stewart’s study and on his desk was a series of letters from a young woman. I read them, of course. Then I read a page from his journal, which, it was clear, was inspired by her. He wrote, “I think of your breasts. I feel the earth. My mind reels.” I found him in the kitchen and confronted him. “That’s an assignment my analyst gave me,” he insisted. “It’s not about a real person.”

I was seeing that same analyst. Stewart had seen him first, then stopped after a few years and got a new referral from Dr P to a female colleague, claiming, “You’d do well to work with the feminine aspect.” Stewart thought I might want to see Dr P, now that the two of them were done. I’d always been fascinated by dreams and symbolism, and Stewart thought he was good – what could it hurt to get into Jungian therapy? I started seeing him weekly.

How Dr P must have struggled, listening to me all those months as I droned on about self-doubt and my fear of abandonment by Stewart. Then, at one session, as I was recounting how Stewart and I had just celebrated a “year of monogamy,” I saw that Dr P was moving his head from side to side.

Related articles:

“No,” he said quietly.

I could barely breathe. The room felt as though it was tilting. It was like an eerie horror movie.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“What do you mean?” My heart felt wild, beating hard. “I just can’t do it any more,” Dr P said. “I care about you, and it’s true. Stewart is not faithful.”

A heart attack felt possible. Silence.

I left the session and got on the highway. I drove straight to school and found him teaching a class on Nathaniel Hawthorne – I caught his attention through the window in the door. He came out immediately. “I’ve just been at Dr P’s,” I said and stared at him.

“I’m finishing up. Meet me in the cafeteria.”

“He told me about the other women.”

His blue eyes suddenly looked cold and alien as he turned towards me. I had never seen this look before; it was like looking at a stranger. I took a step back.

“You just ended the relationship,” he declared.

We didn’t make it to the cafeteria.

That night we sat at the table in the rustic kitchen that had once given me such comfort. First, he wouldn’t admit the truth – he wore a spaced-out gaze, as if he were formulating a perfect alibi. He said my insecurity was stifling, but I barely heard; I was in my own bubble.

‘I care about you, and it’s true. Stewart has not been faithful’

‘I care about you, and it’s true. Stewart has not been faithful’

I cried like a desperate baby. I ran out into the backyard and dropped on to the snowy ground, hitting my head again and again. I was so dependent on this man, and not just the affirmation of his attention and adoration – my whole identity had been subsumed by his world. His music, his ideas, his friends. I felt like a hatchling, kicked prematurely out of the nest. Eventually I came back inside and we held each other, sliding to the floor. He didn’t ask for forgiveness, but we wondered together, could we repair this? In that embrace, we gathered forces against the therapist.

The next morning I wept in an urgent call to Dr P. “How could you traumatise me that way?”

“I suppose, upon reflection, it was like the hand of God coming down and I can see that…” Jungians loved Biblical references. “It was hard to watch you suffer.”

I left them both. I moved out of Stewart’s house and into a studio above a garage and concentrated on writing poetry. I cried a lot and lost a lot of weight. I thought I’d never recover. A lot happened in that studio; you know, the way it is in your 20s and you’re trying to get your self-esteem back and you have a crazy way of doing it.

Stewart’s new woman was even younger than me, and beautiful. I would drive by the old place, hoping to get a glimpse of her. It was like picking at a scab. One day there she was, in an old Volvo, long dark straight hair, a crisp white cotton sleeve hanging out the window. I followed the Volvo for a while, watching as her long arm turned the wheel. She seemed more graceful than me in every way.

Stewart began to call me, late at night. I’d let him come over to my studio above the garage and we’d have melancholy sex. He’d leave at 3am and return to the Volvo girlfriend. I was now “the other woman”. This was a man who slept with another woman during his honeymoon with his wife – I’d known this all along, but had caught that dangerous “it will be different with me” virus. Some months later I was suddenly cured – I broke off all contact. It had to be swift and severe; abstinence at the beginning of sobriety.

When I heard that Stewart had died, I’d moved to another city and was living with a gentle man. There was an old neighbour from those days living with Stewart who had always remained a friend; I ran into her once in a while. At first she told me he was sick, in the hospital, and not wanting to see anyone. But I didn’t want to know too much, and she was tentative – I still wanted her to hate him with me. At least she shared that the Volvo woman hadn’t lasted very long. Eventually, she told me he’d died and I imagined all the women who might appear at the funeral, like a procession from a Fellini film.

Over the years Stewart’s name has been hard to say aloud. It’s been like calling forth the winds of betrayal, but it was the last time I’d completely dissolve into someone else because of how lost I was, or how special they made me feel. Stewart had once asked me if I’d ever considered having my nose “fixed”. I was shocked and hurt at the time, but I said no. Turns out, my nose was fine.

A while after the midnight visits stopped, I ran into him in the street. I looked away. I didn’t even risk saying hello. That’s how you have to do it.

For more information on Binnie Klein’s music project, go to inthesetrees.com