Last Wednesday Tiananmen Square in Beijing hosted a massive parade. The event commemorated the 80th anniversary of the end of the second world war in Asia. But with hundreds of lethal weapons complementing the thousands of soldiers marching in perfect formation it was also an advertisement for China’s new military confidence – a strong contrast with the weakness that allowed Japan to invade the country in 1937.

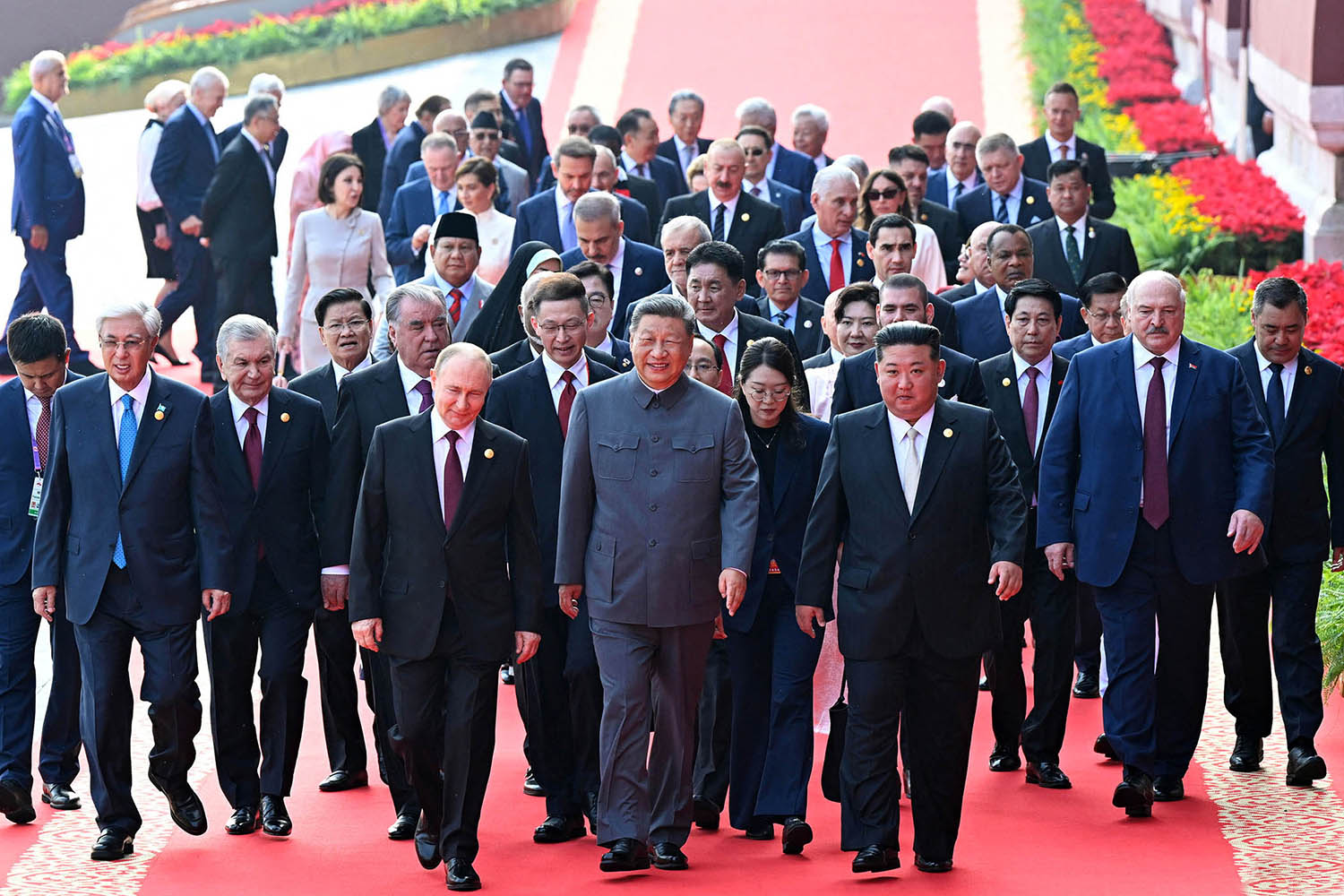

Although Japan was defeated in 1945 by an alliance of the United States, the British empire and China, the history they commemorated was distinctly Asia-focused and the key leaders who came to the ceremony were almost all Asian. The presence of Vladimir Putin prevented any senior Americans or Europeans attending, but it didn’t prevent him being feted by Xi Jinping, with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un making up a trio.

The eclipse of America’s war record and the rise of Asia’s narrative in the second world war seems to foreshadow a new prominence for Asia’s role in global politics. The parade came just days after another striking geopolitical troika when Putin was greeted by Xi and Indian premier Narendra Modi at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation meeting in the northern Chinese city of Tianjin.

These two events – producing two striking images – have led some to question whether this was the week that the Asian century truly began.

The retreat from liberal values in much of the west has given Asia’s agnosticism about politics freer rein. Asia still maintains liberal democracies (South Korea, Taiwan), less liberal ones (India, Indonesia) and authoritarian states (China, Vietnam). But Asia’s leaders do not criticise each other on internal governance. The celebration of the second world war in Beijing may have referenced anti-fascism, but it was certainly not a celebration of the triumph of democracy.

Instead, last week suggests that Asia may be at the heart of new partnerships. The picture of Modi, Xi and Putin together is in some ways the mirror image of the encounter between Nixon and Mao in 1972, when the US managed to become closer to a China that was at odds with the USSR. This time round, the odd couple is Modi and Xi, whose geopolitical friction is very real, but who deliberately chose to take a photo opportunity with each other along with Putin as a way of reminding the US that Asia’s rising powers have options other than the west.

This increasing geopolitical assertiveness comes in part from Asia’s growing centrality to the world’s economic future.

Some 50% of global GDP is in Asia, and the IMF projects regional growth of nearly 4% in the near future. The effect of the new Trump tariffs is not yet clear, but they may have the effect of making trade less global and more regional. Asian countries may form even deeper supply chains with China, which is already the major trading partner of almost every country in the region.

One factor above all may shape it in the next few years: energy. Geopolitics was also shaped by energy in the 1970s, but half a century ago it was a battle over just one fuel, oil. Trump’s energy policy is much more about a fork in the road: the US will return to fossil fuels, leaving green energy to develop elsewhere. And China, perhaps to its surprise, has been left in the EV driver’s seat when it comes to solar, wind, and even nuclear energy. After all, many of the growing economies in south and south-east Asia are also the countries most vulnerable to climate change. They need to pacify an emerging middle class with aspirations to better jobs and a more consumerist lifestyle. They also need to ensure that hurricanes, typhoons and other weather patterns that threaten the region don’t become worse.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The Trump administration’s answer to their energy hunger is that they should buy more US-produced gas and oil: the US has recently pressured India to stop buying so much from Russia. Asian nations won’t stop buying fossil fuels any time soon. But they will want bigger solar farms and more wind turbines, and now they will get them from China. China itself will continue to be a major emitter of carbon. However, it has recently announced a big new hydropower plant in Tibet, which may yet cause friction over water supply with India and other countries downstream, but is a sign that China intends to dominate what it calls “ecological civilisation”.

This idea seeks not only to shift over time toward renewable energy, but to associate it with a wider moral message, particularly resonant in the global south, about dealing with climate change. The Biden administration’s misleadingly titled Inflation Reduction Act was in large part an incentive to create green energy capacity in the US for use in the democratic world; much of the plan has been cancelled under Trump. Unless Europe steps in as a major manufacturer of green energy technology, China is likely to dominate that sector for decades as an authoritarian near-monopolist on a major global public good. China has a good chance of dominating the struggle for energy generation for years, maybe decades. Why will Asia need to generate so much power? The newest technologies will demand it: as more of daily life in the 2020s and 2030s involves AI, the huge, power-hungry data farms needed to support it will become a key part of debates on energy and data sovereignty.

Meanwhile, Europe is in a bind. The famed German manufacturing sector is faltering and its longstanding success at selling cars into China’s immense market has crumbled as homegrown EV brands such as BYD have become dominant. In AI and 5G, China continues to dominate the field as Europe fails to innovate. As the US withdraws funding from some key areas of biotech, such as mRNA vaccines, Chinese influence will continue to grow in key pharmaceutical fields.

However, underlying geopolitics will still place obstacles in the way of Asia’s giants cooperating on economics. Despite Modi’s recent friendly encounter with Xi, India and China remain wary of each other. The dispute between the two countries over the border in the Himalayas is a reminder that there are potential conflicts just under the surface across the region.

Asia has been broadly peaceful for years. But there is no automatic reason that this will remain the case. In the early cold war, conflicts broke out in Korea and Indochina, and even in recent years there have been small-scale but deadly confrontations between India and Pakistan. Today, the fear of war is greater than a generation ago. Xi has indicated his desire to “resolve” the Taiwan issue by unifying the island with the mainland. A full-scale invasion remains unlikely, particularly if the US remains steadfast in its willingness to offer support for the democratic island. But it is not unthinkable, and the cost to the world economy would be devastating: one report places it at $10tn.

The economic prosperity of Asia is dependent on complex supply chains, financial flows and overall predictability. A war would blast those assumptions into pieces, triggering not just a regional but a global recession. Nuclear brinkmanship by North Korea, or in south Asia, or a naval confrontation in the heavily-travelled South China sea might all have the same effect.

The parade in Beijing marked the end of a conflict that devastated Asia eight decades ago. Today, the region is coming of age as a driver of global economic and technological growth, as well as increasing geopolitical heft. But if they want an Asian century, its leaders will have to do much more to prioritise peace.

Rana Mitter is ST Lee Chair in US-Asia Relations at the Harvard Kennedy School and author of China’s Good War: How World War II is Shaping a New Nationalism

Photograph by Indian Presidential Office/UPI/Getty Images. Other photograph by TR/KCNA via Getty Images