The US embassy in Bolivia, like a fortress behind its perimeter wall, has been a hulking, silent presence for almost 20 years. Back in 2008, the country’s leftwing president, Evo Morales, accused Philip Goldberg, the US ambassador, of conspiring against his government – and kicked him out of the country.

The embassy has lain near dormant ever since.

But Morales is no longer in power. His party, the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS), has imploded. And on Sunday Bolivia is set to swing to the right as it chooses between Rodrigo Paz, a centrist senator, and Jorge Quiroga, a conservative former president, in a presidential runoff.

Both candidates have said they will rebuild the relationship with the US – just as Donald Trump’s administration places Latin America at the heart of its foreign policy.

“The US-Bolivia relationship has been in the deep freeze for decades,” said Benjamin Gedan, a former state department official. “Both sides bear some responsibility for the breakdown. But the duration of the estrangement is mostly attributable to Morales and his political movement.”

Morales’s antipathy to the US predated his time as president. As a farmer of coca – the leaves of which are chewed by tradition in the Andes, but can be processed into cocaine – Morales was targeted by forced eradication campaigns in the 1990s as part of the US-led “war on drugs”.

It was in leading the resistance to these campaigns that Morales rose to prominence, first in the coca farmers’ union, then in the MAS, which he led to power in 2006. Soon after, when his government was rocked by secessionist protests in the eastern lowlands, Morales perceived the hand of the US behind them.

First he removed the ambassador. Two months later he did the same to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Then, in 2013, it was the development agency USAid, which Morales accused of having “political rather than social” ends. The MAS instead cultivated relationships with China, Russia and Iran, while peppering its speeches with invective about el imperio – the empire.

Related articles:

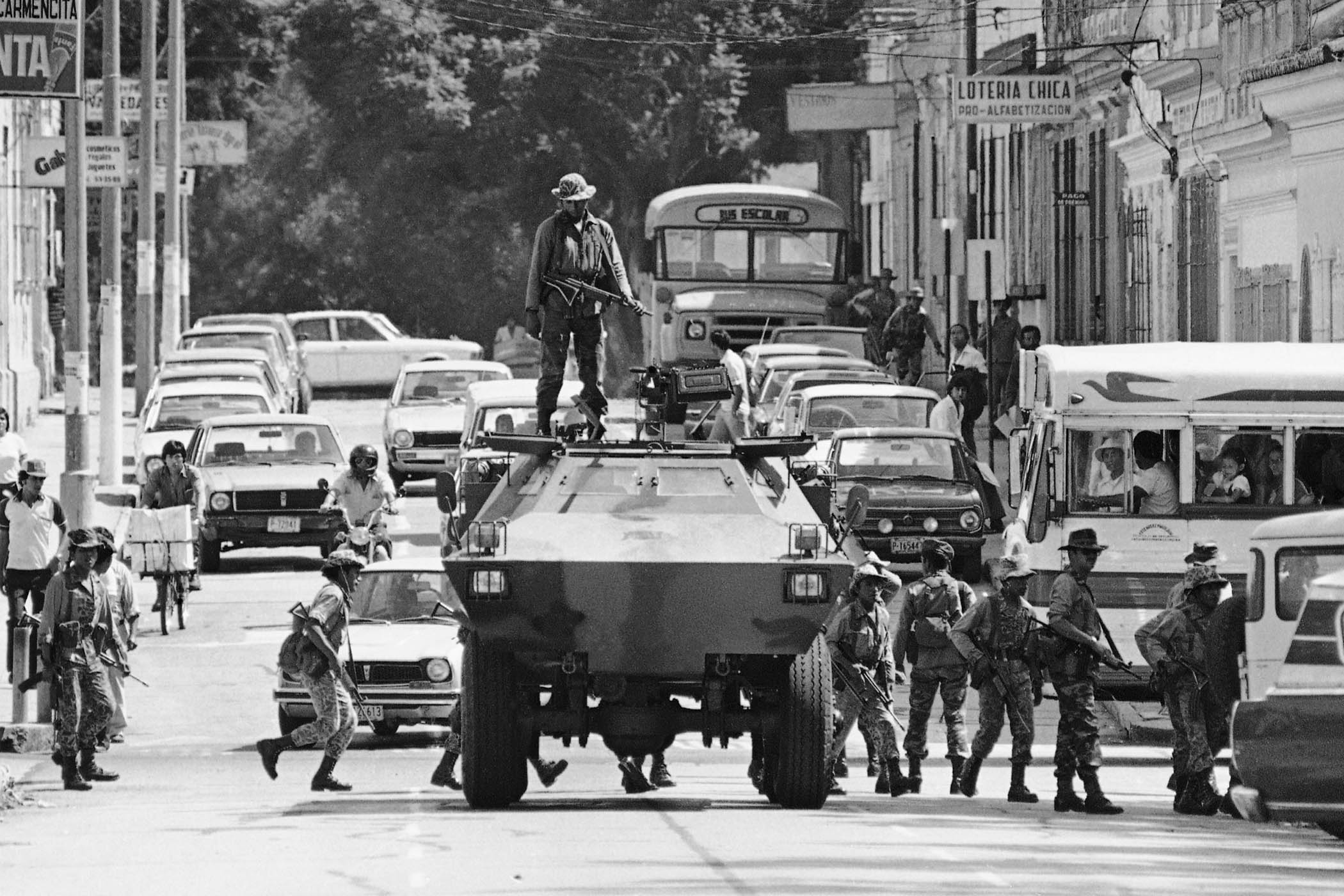

It wasn’t alone: other leftwing governments in the region, such as the regimes in Cuba and Venezuela, have long shared animosity towards the US, stemming from its history of military interventions and support for dictatorships during the cold war era.

But this election will mark a dramatic change. The infighting and the country’s economic crisis are of MAS’s making. Having won the 2020 election with 55% of the vote, it scraped 3% in this August’s first round. That means the next congress will be dominated almost entirely by centrist and rightwing groups. A new US ambassador could return within months.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The US demands it gets its way in the western hemisphere. It is willing to use force

The US demands it gets its way in the western hemisphere. It is willing to use force

Benjamin Gedan, ex-US state department official

It is just one of a string of elections in the region over the coming year that could see leftwing governments replaced by more rightwing, market-oriented ones – notably in Chile and Colombia, helping the Trump administration advance its new hemispheric agenda.

“US engagement in Latin America is more intense than it’s been in decades,” said Gedan. “But it’s also narrower: there’s an obsession with reducing migration and a focus on disrupting drug trafficking.”

This signals a revival of the 1823 Monroe Doctrine, in which the US marked the Americas as its patch and warned European powers against interference – only this time the rival is China. “The philosophy is the same,” said Gedan. “The US demands that it gets its way in the western hemisphere – and is willing to use force when necessary.”

In the case of Bolivia, Gedan anticipates “a fairly long honeymoon”, starting with the exchange of ambassadors and discussions about US investment. But the Trump administration may press for changes to Bolivia’s international relations – and to its coca policy, which allows tens of thousands of farmers a small plot to provide leaves for chewing, though in practice a part goes to cocaine production.

Bolivia could take cues from other Latin America countries – such as Mexico – which have managed to satisfy the Trump administration with tactical concessions. That might mean sacrificing ties with Russia and Iran, but not China, says James Bosworth, founder of consultancy Hxagon. “In Latin America, Russia and Iran are trolls,” said Bosworth. “China actually has interests – including in the mining and energy sector in Bolivia.”

Evo Morales with supporters in March this year.

On coca, it could mean inviting the DEA back and perhaps extraditing some drug traffickers to the US. “But they would not be thrilled if the DEA were to start demanding aerial fumigation of coca in Bolivia,” said Bosworth. “That’s where you end up with massive protests and political instability.”

The backdrop to this will be the White House’s willingness to act unilaterally – as shown again last week, when it destroyed a fifth alleged drug trafficking boat in the Caribbean, near Venezuelan waters, bringing the death toll to 27. The US has amassed ships and soldiers in the region, prompting fears in Caracas of a possible attack. Last week Trump confirmed he had authorised the CIA to conduct covert operations in Venezuela.

Yet the regional response to these strikes has been unusually quiet, perhaps reflecting the little love for drug traffickers and the Venezuelan regime – but also a fear to speak out.

“Muted is an understatement,” said Gedan. “This is a region that jealously guards its sovereignty – understandably, given the history of US military intervention – and which generally has very little tolerance for this type of US armed action, regardless of ideology. But it’s been almost silent.”

That does not mean, however, that there would be backing in the region for regime change in Venezuela, warned Bosworth. “The fact they have some support for going after drug boats does not mean they have support for regime change and boots on the ground.”

Photograph by Pablo Rivera/Getty. Other picture by Fernando Cartagena/Getty