Today is the Dalai Lama’s 90th birthday, with celebrations kicking off with his Compassion Rising world tour – a series of events organised to promote “peace, unity, and the enduring message of His Holiness”.

Meanwhile, the Tibetan monk has used his birthday to cause a little trouble in big China by confirming in a video message that he will have a successor, putting to rest speculation over whether the 600-year-old institution will end when he dies – and setting India and China against each other.

Dalai Lamas are reincarnated after they die, according to tradition, and in his most recent memoir, Voice for the Voiceless, published in March, the 14th Dalai Lama said his successor will be born in the “free world”. The Chinese government, which annexed Tibet in 1950, disagrees, insisting that the Communist party would choose a successor from inside China.

India, home to the Dalai Lama and over 100,000 Tibetans in exile, backs the Buddhist leader, setting up a potentially explosive final chapter in his life. To add a little spice, the smooth-headed Ocean of Wisdom, has suggested he may return as a “mischievous blonde woman”.

Alexander Norman, author of the first authorised biography, The Dalai Lama: An Extraordinary Life, suspects that the priest may already have chosen who will follow him. “I wouldn’t be in the least bit surprised if he has found a successor,” he says.

The Dalai Lama has said that we ordinary folk cannot manifest an emanation before death, but superior Bodhisattvas such as he, who can manifest themselves in hundreds or thousands of bodies simultaneously, can. It’s a sharp political move if he has. By anointing a living successor, he can ensure that the process can proceed without the missing 11th Panchen Lama, one of the key figures in that process, who was kidnapped along with his family by Chinese authorities in 1995.

Such political savvy feels at odds with his Instagram profile, which has more than a whiff of a wellness app about it: “The purpose of our lives is to be happy”, “where ignorance is our master there is no chance of peace” and “be kind whenever possible. It is always possible”. You get the idea.

As well as being a soundbite whizz, he is also “a great tease”, according to Norman. “In the west he’s seen as a sort of Peter Sellers at the end of Being There, doing no wrong and gliding four feet off the ground. But his nickname for me was goshimbo, which means four-headed, big-nosed one, and when I told him Hodder had sold the rights to the biography in America, France, Germany, Italy and Japan he said ‘all because of one stupid Englishman’.”

He has suggested he may return as a ‘mischievous blonde woman’

He has suggested he may return as a ‘mischievous blonde woman’

Journalist Fiona Lensvelt interviewed him for The Times in 2015 and found him “especially warm and quite tactile, not in a weird way,” she explains. “He would laugh along to his own jokes, which I found amusing, and pat you on the arm to get you laughing a bit more.”

The Dalai Lama was born Lhamo Thondup in 1935 to a Tibetan farming family in Taktser, a tiny village in the then Tibetan province of Amdo (in what the Chinese now call Qinghai). He had two sisters and four brothers and his family was already on the religious map. His older brother Thubten Jigme Norbu had been identified as the reincarnation of a 17th-century lama, Taktser Rinpoche, in 1922 by the previous Dalai Lama. There was no precedent for one family to produce two reincarnated lamas, but the small house was particularly religiously fertile. The youngest son, Tenzin Choegyal, was recognised as the reincarnation of another high lama, Ngari Rinpoche.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The Dalai Lama’s eldest sister, Tsering Dolma, became a politician and founded the non-profit refugee organisation Tibetan Children’s Villages (TCV); his younger sister, Jetsun Pema, was president of TCV, and the remaining brother, Gyalo Thondup, ended up working for the CIA.

Lhamo Thondup’s life changed when he was two years old. The mummified corpse of his predecessor turned its head to look towards the toddler’s family home during embalming, while Tibet’s temporary ruler had visions and dreams that led monks to the boy. After some simple tests – the child always picked out objects owned by his predecessor – they whisked him off for his education, induction and installation as Tibet’s spiritual and political leader. The process, His Holiness recalls, was “a somewhat unhappy period of my life”. In 1939 (ahead of a spiritual ceremony, at the age of five, the following year), he was given the name Tenzin Gyatso. His political enthroning took place a decade later in 1950 when he was 15.

Shortly afterwards, Chinese troops entered and occupied Tibet. Leading a population of just six million and with an army of 8,500, he turned to the UK and America for help. None was forthcoming. He attempted an uneasy truce, but in 1959 the Chinese tried to capture him and the people rose up to protect him. He fled across the border to India in disguise and has lived in the Himalayan foothills ever since.

Perilous escapes aside, it was not a typical adolescence: he had to remain celibate and was banned from masturbating. “He said he’s very lucky that he doesn’t feel sexual urges so that wasn’t a problem for him,” Norman says. “He said he can certainly appreciate a beautiful woman but doesn’t really get beyond that.”

The Dalai Lama set up his palace-in-exile in Dharamshala in Himachal Pradesh in northern India, in a compound that looks much like the rest of town except for the presence of heavily armed Indian soldiers. From there he has called for a peaceful “middle way” – non-violent resistance but a demand for Tibetan autonomy. Some celebrities – such as Richard Gere – encountered him on the 1970s hippie trail, but it was the Nobel peace prize in 1989 that pushed his struggle into the mainstream.

His high profile has landed him in trouble – his US fundraiser, the Tibetan monk Tenzin Dhonden, was replaced in 2017 after allegations of corruption, which they denied, and there was some outrage in 2018 when he spoke at an event organised by Keith Raniere, the founder of the sex cult NXIVM – but it has also enabled the Free Tibet movement to stay in the public eye.

As a result, the Tibetan movement is working closer than ever before with Hong Kong, Taiwanese and Mongolian groups – and Chinese dissidents. “They show much more sympathy, understanding and awareness of our cause,” says Tenzin Rabga Tashi, the campaigns lead for Free Tibet. His succession will be a testing time. If China attempts to impose its own choice, Tashi is clear that Tibetans will reject them. “Already the Indian government has shown support and we’re hopeful that the UK government will also stand by His Holiness’s decision,” he says.

Norman is even more pointed. “You’ve got to remember that this whole idea about peace-loving Tibetans is a tremendous nonsense,” he says. “The Dalai Lama preaches peace and inspires his people but they are perfectly prepared to fight if it comes down to it. If his successor is appointed by the Chinese… his people will go to war.” He is doing what he can to avert such a conflict, says Norman. “And he is a very clever man who’s streets ahead of most people. He might pull it off.”

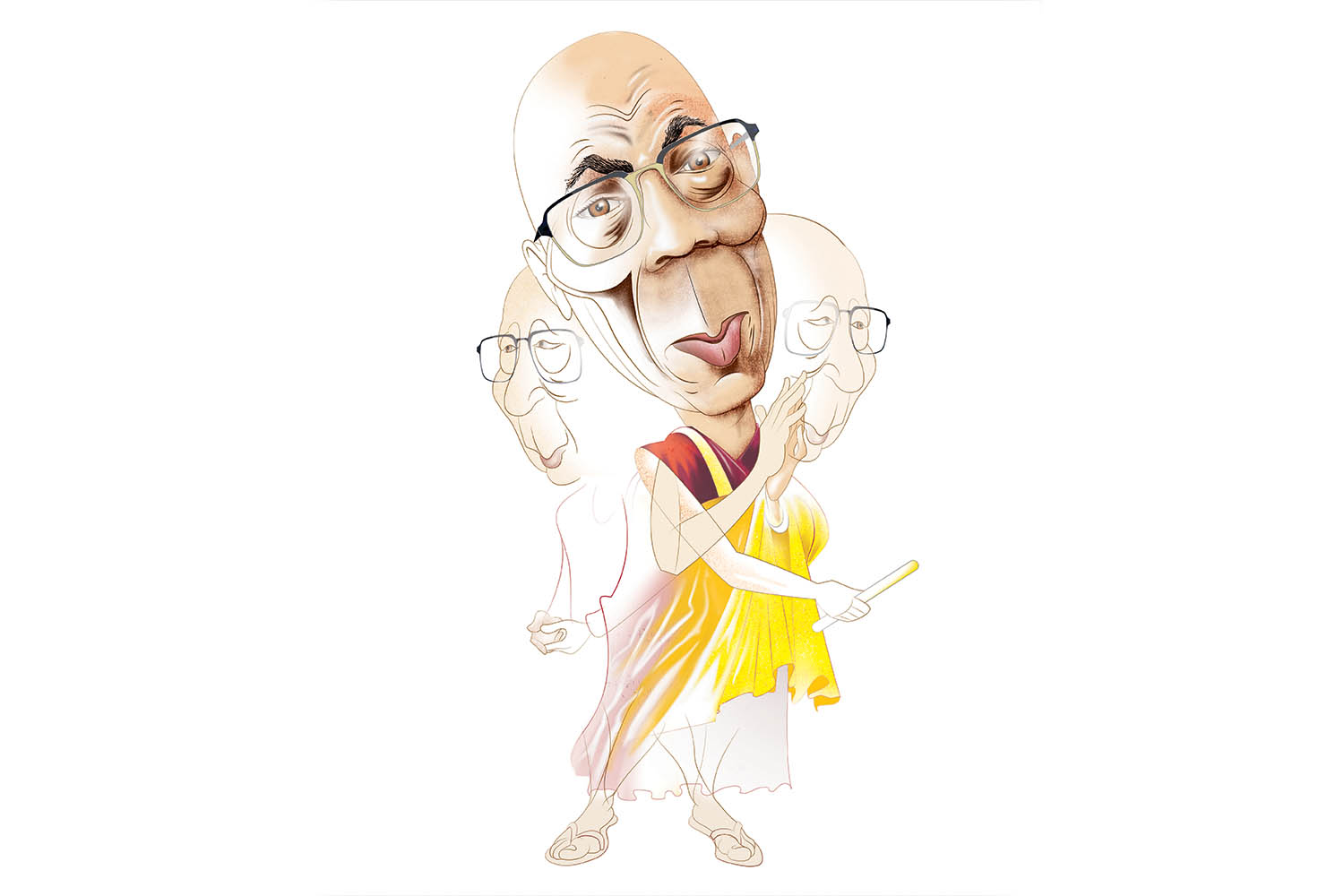

Illustration by Andy Bunday