The fate of the French prime minister was decided in the national assembly yesterday, when François Bayrou and his centre-right government lost a confidence vote.

But the future of the country will be shaped elsewhere – online and on the streets. Over the summer, two opposing campaigns have emerged on social media to amplify the voices of ordinary voters.

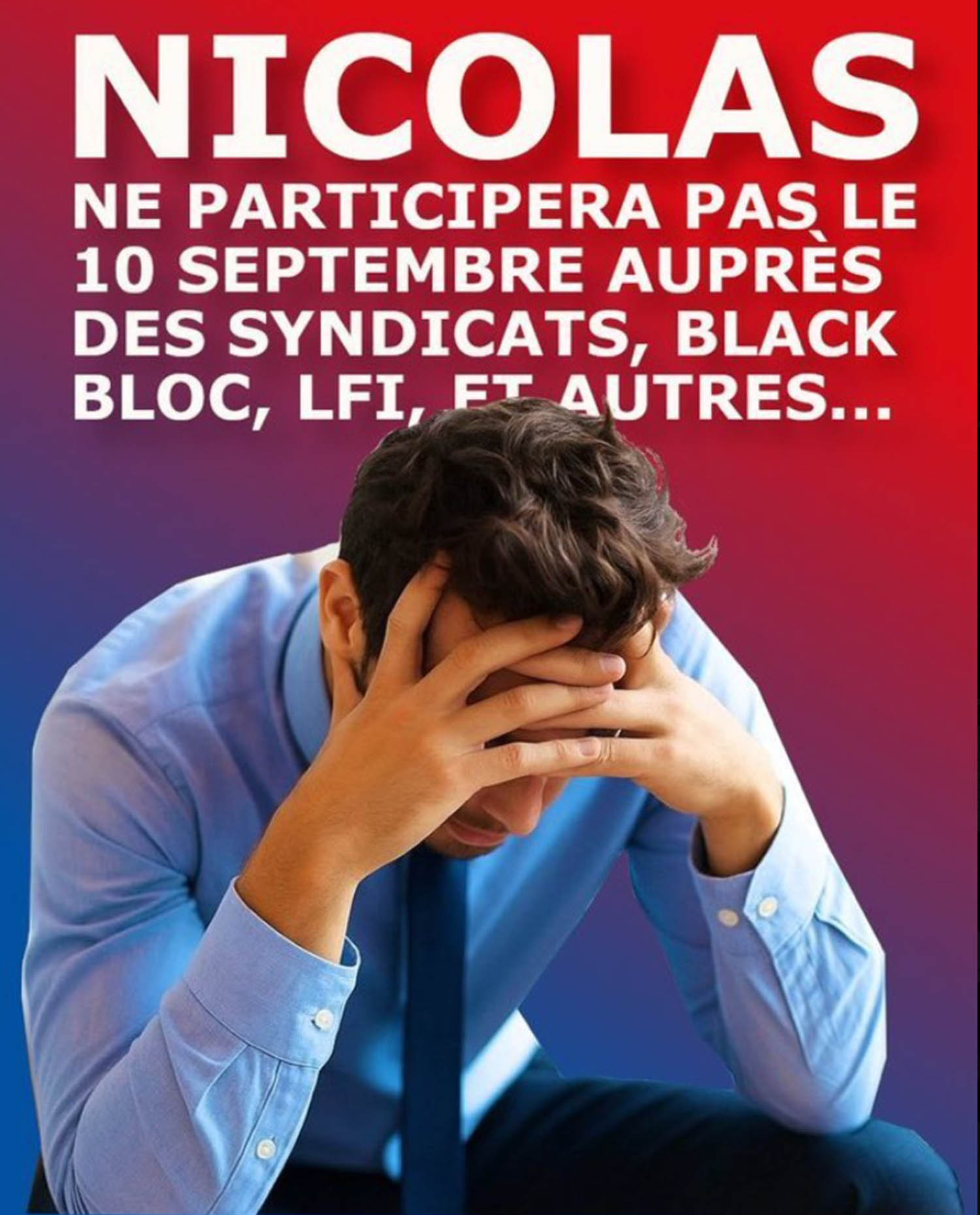

“C’est Nicolas qui paie” (Nicolas picks up the bill) began as a rightwing meme; a white-collar worker pictured with his head in his hands, virtual Nicolas despaired of paying high taxes to fund what he viewed as a nanny state.

The idea was that his taxes were going towards benefits for migrants and for pensioners to go on cruises, while he was getting nothing back.

The meme became a movement. Conservative and far-right politicians have cautiously adopted Nicolas. Anxious not to alienate cruising pensioners – boomers are key supporters of Les Républicains and Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (National Rally) – they have leaned into the anti-immigration rhetoric in which the fictional Nicolas finances the benefits of the fictional “Karim”.

Bruno Retailleau, France’s rightwing interior minister, has said that Nicolas embodies the sense of injustice felt by part of the population. “It’s the France of honest people, who pay their taxes, who work … who don't make a fuss, not because they have nothing to say but because politicians often don't care,” said Retailleau to a political thinktank last month.

“This is what I call the silent majority. They feel a sense of injustice because it is Nicolas who always pays.”

On the left, the Bloquons Tout (Block Everything) movement has also evolved from an online campaign, this time to hasten economic and political collapse in France by paralysing the country.

The campaign emerged on the Telegram and Signal networks in May from a citizens’ collective in northern France calling itself “the Essentials”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The campaign has since spread over X, TikTok, Facebook and Signal, and has been hailed as the new gilets jaunes movement, in reference to the wave of popular but increasingly violent yellow-vests protests that swept throughout France in the two years before Covid.

According to analysts at Visibrain, which monitors social networks, there are signs the Bloquons Tout hashtag was artificially amplified with astroturfing, whereby fake accounts or bots publish thousands of messages a day to boost content.

But the political scientist Antoine Bristielle, a director at the Jean-Jaurès Foundation thinktank, said its recent report profiling supporters of Bloquons Tout had found they were overwhelmingly young, highly educated, reasonably well-off and supporters of the radical left.

Bristielle said both online movements were seeking to revolutionise France, not through traditional street marches and protests but as social and political social media influencers.

“They hope that by getting enough support on social media, they can bring about change,” Bristielle said. “The common characteristic of both is that they were born outside of the political parties. Usually, it is the parties that express their vision of society, but social networks allow the people to express their political visions.”

Bloquons Tout will try to shift the movement to the streets this week, announcing its intention to paralyse the country on Wednesday but exactly how remains unknown. A briefing note from French intelligence and police warned that an estimated 100,000 protesters may block strategic transport energy and defence sites, train stations, petrol refineries and Amazon distribution centres as well as carrying out acts of sabotage.

The problem is that Macron is determined not to appoint someone from the left as prime minister because he fears they will unpick everything he has done up to now

The problem is that Macron is determined not to appoint someone from the left as prime minister because he fears they will unpick everything he has done up to now

Antoine Bristielle, political scientist

There is a sense of deja vu about the impending political crisis that even supporters of Emmanuel Macron admit is of the president’s making. Last year, he called a snap general election with the aim of consolidating his government’s control of parliament after his centrist party had performed badly in European elections.

Instead, the election saw a surge in support for the far-right National Rally, whose progress was only stymied by a leftwing alliance in the second round vote that left the national assembly split into three roughly equal groups, none of which had a majority.

Macron could have chosen a prime minister from the left who, with the support of his own MPs, might be able to form a majority coalition government.

“The problem is that Macron is determined not to appoint someone from the left as prime minister because he fears they will unpick everything he has done up to now,” Bristielle said. “So he chooses someone from the centre or centre-right, but they do not have the support of enough MPs.”

Macron’s chosen prime minister, Michel Barnier, was forced out after three months following MPs’ rejection of his proposed budget. Now his replacement, Bayrou, has faced the same fate. He proposed cuts of €44bn to public spending, achieved by freezing pensions and benefits, and cancelling two public holidays, along with other measures.

That Bayrou and his government would fall on Monday seemed certain. But what happens next is the unresolved question.

Macron could appoint a new prime minister, who will face exactly the same budget crisis as their two predecessors, or dissolve parliament and call a new general election. The president is unlikely to heed calls to resign.

Bristielle said that, despite their rejection of party politics, the success of the “C’est Nicolas qui paie” and Bloquons Tout movements will depend on which of their demands are adopted by mainstream parties. “We are already seeing political parties trying to capitalise on these movements and reclaim their support,” Bristielle said.

He added: “If Emmanuel Macron’s response is not what people want, this could provoke much greater anger. It’s difficult to know what comes next.”

Photograph by Zakaria Abdelkafi/AFP/Getty Images