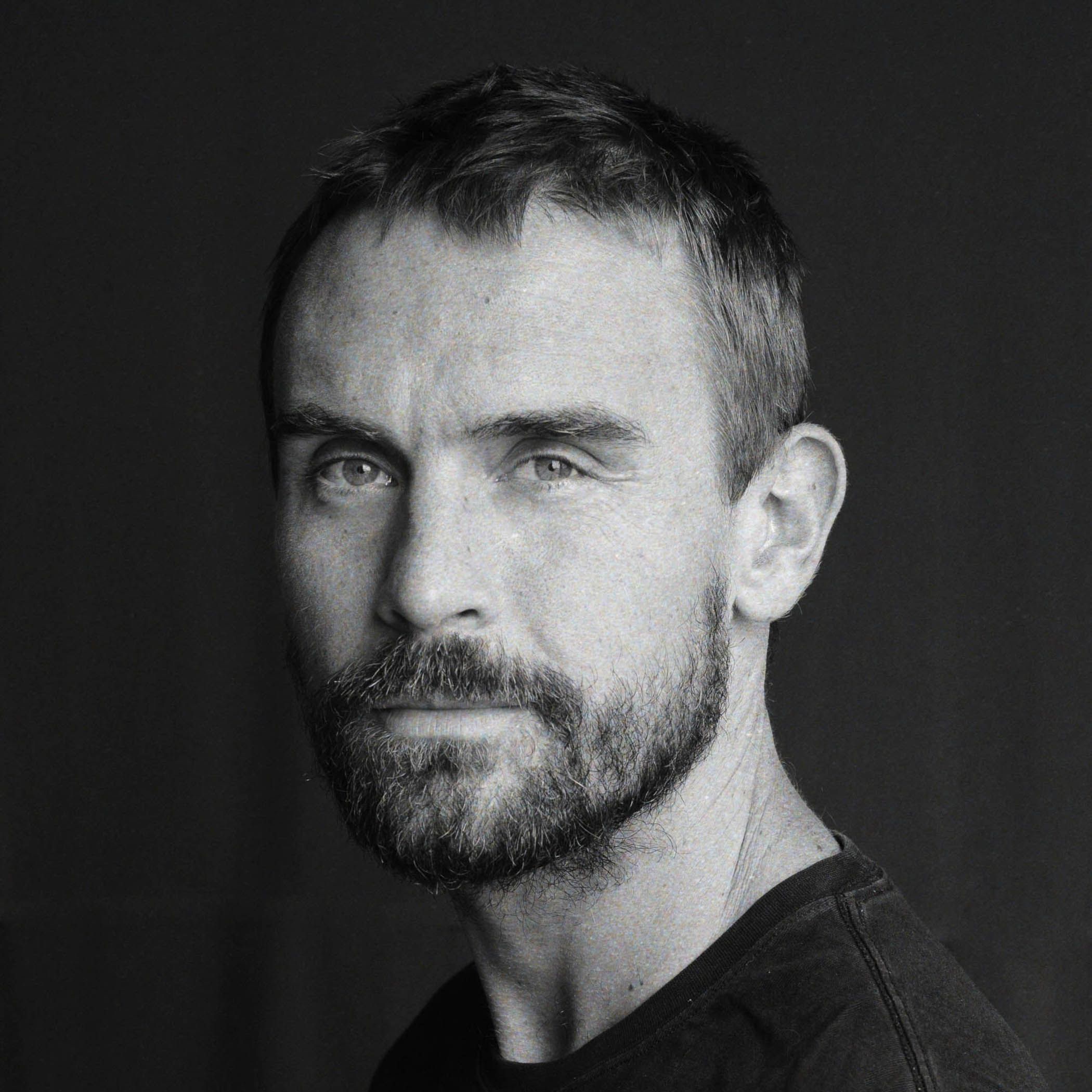

Words and photographs by Oliver Marsden for The Observer

Nour turned a pebble over in her hand and stared at the Mediterranean Sea. The other hand holding her headscarf in the wind while protecting her eyes from the Syrian sun.

It was the first time the 24-year-old had been to the beach and she couldn’t tear her eyes away from the huge expanse of blue.

A few feet behind, her mother, Fatima Sallat, a school teacher from Idlib, smiled at the scene on Wadi Qandil beach, a popular tourist spot 20 miles north of Latakia.

“The first thing that crossed my mind when arriving here was how happy I was for my children to finally see the sea,” she said, grinning at her daughter. “At last, we can traverse our land freely.”

Just a stone’s throw along the beach, men and women sipped local Afamia beer while catching rays in their shorts and bikinis. As a family walked past the scene in full niqabs, the beach became a study in contrasts: the uncovered gazing at the veiled, the veiled gazing back – each registering the other with equal curiosity.

During Syria’s 13-year brutal civil war, much of the country was divided and inaccessible. Last December, everything changed.

Ahmed al-Sharaa sprung out of Idlib, the northern city he controlled with his Sunni Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), and thundered south towards Damascus. The soldiers of Bashar al-Assad dropped their weapons, tore off their uniforms and fled into the night.

Nour Sallat, from Idlib, on the shore of the Mediterranian for the first time

Assad himself, whose family had ruled Syria for 53 years, escaped on a plane to Moscow. With no opposition, al-Sharaa swept into Damascus on 8 December and ended the war.

In Syria’s new order, few places have changed as sharply as the coastal region of Latakia and Tartus. Traditionally home to members of the Alawite community, a religious offshoot of Shia Islam and the sect that the Assad family belonged to, the coast was spared much of the civil war’s fighting. Shielded from the worst of the violence, Alawites enjoyed a degree of privilege and stability denied to other sects.

Under Assad’s staunchly secular rule, religion was kept firmly out of public life: the beaches brimmed with music, alcohol and bikinis.

This summer, families from the northern cities of Idlib, Aleppo and Raqqa flocked to the coast, many dipping their toes in the sea for the first time in their lives.

‘It’s amazing being here. We feel completely different and very happy. We can’t wait to swim’

‘It’s amazing being here. We feel completely different and very happy. We can’t wait to swim’

Ahmed, visitor from Raqqa

But while the new arrivals can enjoy freedoms previously denied, the fall of Assad has had a dramatic effect on the lives of Alawites, not all of whom supported the former president. It is not just tourists who have come to Latakia and Tartus – security is now also provided by Islamist allies of the new president.

“They shouldn’t be responsible for the only stretch of coast,” a local bar owner complained. “We are seeing behaviour at checkpoints we have never seen before. They are asking what religion people are. It’s ruining my business.”

The coastal region has become a microcosm for the whole country. The people are free, but fears remain. President Sharaa, welcomed like a rock star at the UN general assembly in New York last month, has yet to earn the trust of swathes of his own people. The inclusiveness he promised has yet to materialise, and his own men have been accused of violent attacks against minorities across the nation. Anxiety still runs deep in the new Syria.

Ahmed, Faraj and Abdallah view the sunset having made the 230 mile trip from Raqqa

Sharaa’s speech to the UN was broadcast live in a Tartus square packed with people. As he made the short walk to the podium, the crowd erupted into cheers.

“Syria is reclaiming its rightful place among the nations of the world,” Sharaa told the UN. His words were met with chants of “No God but Allah, Jolani is God’s beloved,” referring to the self-declared president’s nom de guerre. Men and women threw their hands into the air, the new Syrian flag fluttering beside the stark white of the Al Liwa Islamic banner – previously unthinkable in the predominately Alawite city – never taking their eyes off the large screen. All under the watchful gaze of masked security forces.

The square sits in Central Park –originally named Al Bassel Park after Bashar al-Assad’s late older brother, but recently renamed by the new government – 50 miles south of the beach at Wadi Qandil.

As the sun began to set, lights from ferris wheels and sea front cafes flickered into life along Tartus’s corniche. Nearby, three friends from the north-eastern city of Raqqa posed for selfies in front of the sunset. Ahmed, Abdallah and Faraj had made the 230-mile trip to see the sea for the first time.

“It’s amazing being here. We feel completely different and very happy,” Ahmed said, smoothing down his traditional green jubba and checking his hair, before striking a pose and continuing. “We can’t wait to swim. We have only swum in the Euphrates before.”

The group found the journey surprisingly hassle free. Abdallah doesn’t have an ID, just his birth certificate. Where once bribes would have been expected, if he had made it that far at all, the new soldiers on the checkpoints were lenient, they let the men straight through.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

However, Sharaa’s security forces have come under national and international scrutiny following an outbreak of violence on the coast early this year.

Clashes erupted on 6 March after former pro-Assad soldiers attacked new security and defence officials near the Latakia-Tartus highway, killing 22. In response, security forces and civilians acting alongside them launched brutal reprisals, much of it directed at Alawite communities. Around 1,400 people were killed, amid murder, torture, desecration of bodies, looting and arson. The UN Syria commission of inquiry concluded many of the “acts likely amount to war crimes”.

Judge Joumaa al-Anzi, who heads the committee, told The Observer the president’s office had ordered the inquiry and that those arrested would face justice.

“Of 536 possible suspects, we have managed to arrest 42, and the government allowed us to question them. We are confident that all of these men will be held accountable; if not, then the purpose of creating this committee is nullified and void.”

I always feel anxious. I don’t feel safe, especially with these new soldiers in the area

I always feel anxious. I don’t feel safe, especially with these new soldiers in the area

Dr Ghazal, Alawite dentist

But not all share Anzi’s faith in the system. Sitting at the upmarket Junada resort in Tartus, Dr Ghazal, a dentist in her twenties who refused to give her last name for fear of retaliation, told The Observer she no longer felt secure in her own city.

“I always feel anxious. I don’t feel safe, especially with these new soldiers in the area,” she said, wringing her hands under a restaurant table as she watched tourists swim in the small bay nearby.

Ghazal described how she and a group of friends drove to a party one evening months after the coastal violence. “All of us Alawite, seven of us in one big car and the women wearing skirts.” The car was stopped by security forces at a checkpoint and the driver ordered out of the car at gunpoint. Their IDs were taken before the men at the road block started harassing the group for being from Latakia.

“We were terrified,” Ghazal recalled. “After that we learned our lesson. Now the girls go in one car and boys in another.”

Such incidents have affected Ghazal’s relationships. Before 8 December she would sit and chat with friends from different faiths or sects, creed absent from the conversation. Now religion is often a topic and her friendship group is fractured.

Ghazal believes there has been a paradigm shift in power in the region from Alawite to Sunni.

“However, no one minds it as long as we are safe and respected,” she said, before casting an eye around the resort and adding, “In general, I’m not feeling respected.”

Several bar owners have reported problems, including attacks by security forces and licences revoked after footage was shared online of men and women dancing together. In one recent incident, security forces came crashing onto the beach in the dead of night, breaking into resort cabins and chalets as visitors slept. Witnesses described women being dragged from their rooms by their hair.

“I was slapped and beaten in front of my family for asking the internal security why they were doing this,” said one of the victims, who was visiting the region for the first time.

Crowds in Tartus celebrate President Ahmed al-Sharaa’s address to the UN last month

A beach bar owner, speaking anonymously, said 33 men and 22 women were arrested and the bar’s security cameras seized in the raid. One of those arrested said they overheard security services say “they’re being arrested for participating in prostitution”, while others claimed that “the entire area is suspicious”. All of those arrested were released hours later. The bars and cabins remain closed.

Back on Wadi Qandil beach, Nour and her mother sat down with their family to enjoy a home cooked meal as the cool Mediterranean breeze picked up. Fatima’s husband, Sobhi, handed out stuffed vine leaves and kibbeh, a popular dish made by pounding bulgur wheat and meat together into a fine paste, before squeezing it into oval shapes for frying.

“It’s the first time I have been to the sea in 14 years,” he said, brushing sand off his hands. “We have only had a good reception from the people of this region. I was so happy to put my feet in the sea, but even happier that we have got rid of the dictator Bashar.”

Sobhi’s son, Bashir, turned to look over his shoulder as another SUV with Idlib license plates pulled up to the waterfront. The family fixing their abayas as they excitedly spilled out on to the beach. The young man turned back with a grin.

“When the men at checkpoints see Idlib plates they are happy,” Bashir declared. “We’ve gone from being the forgotten governorate, to the star governorate.”