At 6.30am on 7 October 2023, Miri Eisin, a former colonel in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), woke up in Israel to an air-raid siren. “I said to my husband: is this the beginning of the Hezbollah attack?”

A military intelligence specialist, Eisin assumed the Iranian-backed paramilitary group was firing missiles into Israel. “All our intelligence capabilities were built up to look at Hezbollah and the Islamic regime in Iran,” she said. “Then we saw it was coming from the south. And we were like, Hamas? Oh, my God.”

Almost 20 months ago, Israel’s intelligence agencies were humiliated when Hamas launched its surprise attack from Gaza, killing 1,195 people and taking more than 250 hostages. The commander of Israel’s military surveillance agency resigned and public support for organisations such as Mossad fell to an all-time low.

In last week’s attack on Iran, Israel’s spies have taken the opportunity to rebuild their tattered reputation. This time, they were fighting an enemy they knew inside out. “When you look at what we’ve done in the last six days, you see capabilities that have been built over 20 years,” Eisin said.

By the time Israel’s advanced F-35 jet fighters had crossed into Iranian airspace in the early hours of 13 June, Mossad was well established behind enemy lines. As jets buzzed overhead, the agents activated armoured drones and other weapons that had been smuggled into Iran months before. In a matter of hours, entire aerial defence units were destroyed before they could fire on a single jet.

At the same time, Israeli intelligence pinpointed the locations of key Iranian targets, enabling six top nuclear scientists to be assassinated in a single airstrike. On Tuesday, Israel killed Iran’s top military commander – only four days after an airstrike took out his predecessor.

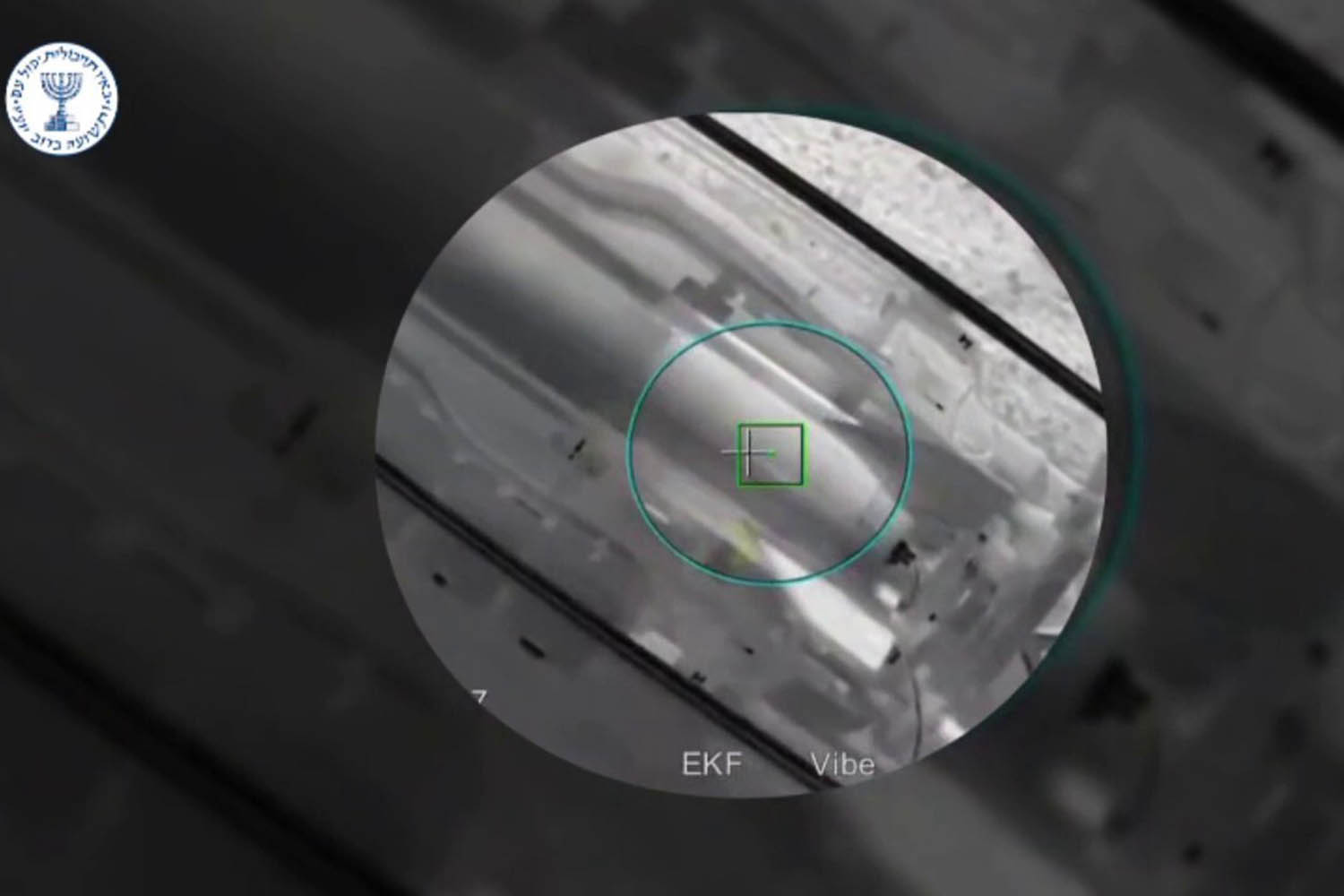

Weapons are smuggled into Iran before last week’s attack.

“It was extraordinary,” said Uzi Shaya, a former high-ranking Mossad member. “The level of intelligence and the translation into action, the way high-value targets were eliminated.”

Intelligence sources described a multi-year operation costing millions of dollars, designed to gain intelligence on Iran from every possible angle. Mossad agents are thought to have posed as foreign nationals to recruit Iranian opponents of the Islamic regime. The spies obtained intelligence that Iran was accelerating its nuclear programme in secret and discussing how to “mate” a nuclear device to a ballistic missile, the Economist reported last week.

Cutting-edge AI technology was used to sift data gathered over years from commercial satellites and from hacked phones, laptops and pagers belonging to Iranian personnel. By the time the strikes were launched, Israel’s military intelligence arm, Aman, and Mossad, its foreign spy service, had amassed a detailed bank of military and nuclear targets.

“I don’t think people realise how much audacity we have,” Eisin said. To avoid Israeli surveillance, a target would have to completely divest themselves of any electronic device – not just mobile phones but anything connected to the internet. “Most people don’t take themselves off the grid,” Eisin said. “You can get to anybody.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Israel has yet to achieve its ultimate goal – the destruction of Iran’s nuclear weapons programme. But the depth of its intelligence operation has spooked Iranian authorities. Almost 30 people have been arrested on suspicion of spying and dozens more for sharing articles “in support of the Zionist regime”.

The country’s intelligence ministry has issued guidance on how to spot collaborators, urging people to be wary of strangers wearing masks or goggles, driving pickup trucks, carrying large bags or filming around military or residential areas. A police poster published on state media advises landlords who have recently rented their homes to notify the police immediately.

‘People were saying we had failed... But the greatness of our agencies is the ability to recover fast’

‘People were saying we had failed... But the greatness of our agencies is the ability to recover fast’

Uzi Shaya, ex-Mossad

For Shaya, and other intelligence agents, Operation Rising Lion – the name for the latest attack against Iran – represents a rehabilitation for Israel’s intelligence agencies.

Shaya was “angry” on 7 October, he said. “We were caught by surprise. The people were saying that we had failed and we neglected them… that we were arrogant. And rightly so. It was painful to hear. But the greatness of our agencies is the ability to recover fast.”

The story of how Israel failed to deal with the threat from Hamas in 2023 while, less than two years later, pulling off an apparently extraordinary operation against Iran, is one of shifting military priorities, missed chances and political miscalculations.

Since fighting a war with Lebanon-based Hezbollah in 2006, Israel has poured millions of dollars into preparing for another major conflict with the militants – and with their backer, Iran. Hamas, in contrast, was viewed as a far less dangerous threat. Right up until September 2023, the Israeli military characterised Gaza as being in a state of “stable instability”.

By 2016, Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, began to allow Qatar to send millions of dollars a month to the Gaza strip in an effort to contain the group. Netanyahu told journalists as far back as 2012 that it was important to keep Hamas strong as a counterweight to the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank.

“The logic of Israel was that Hamas should be strong enough to rule Gaza,” Yossi Kuperwasser, a former head of research for Israel’s military intelligence, told the New York Times, “but weak enough to be deterred by Israel.”

Netanyahu’s encouragement of the Qatari payments, which continued until 2023 and were used to pay government salaries and to buy fuel, was based on the assumption that a steady flow of money would maintain peace in Gaza, as well as a flawed assessment that Hamas was not capable of a large-scale attack.

Israeli intelligence officials now believe that the money played a role in the success of the 7 October attacks, if only because it allowed Hamas to divert some of its own reserves towards military operations.

Shaya was in a personal position to dispute Netanyahu’s approach. He was part of a Mossad unit called Taskforce Harpoon, which was set up in 2001 to disrupt the money flowing to terrorist groups. It brought agents from across counter-terrorism under one roof and gave them a direct report to the prime minister.

Taskforce Harpoon helped instigate financial sanctions targeting Iran and its proxy, Hezbollah. But its investigations into Hamas’s money weren’t taken so seriously. “The resources given to fight against Hamas financing were extremely limited,” Shaya said. “A lot of wrong actions were taken. We didn’t understand that you have to fight the whole package of a terror entity… not [just] the military wing.”

Udi Levy, the head of Taskforce Harpoon, told The Observer his team had amassed detailed financial information on Hamas as early as 2013, when he briefed Netanyahu. “We knew a lot – we knew almost everything,” he said. “But in 2013, when we showed him Hamas’s infrastructure, let’s say that he was less interested.”

Levy said Israel had to be “very honest” about the 7 October attacks. “It happened because the intelligence, especially Mossad, [directed] all its resources only towards Iran and Hezbollah and not to Hamas.”

In 2018, after both Shaya and Levy had left the intelligence services, Israeli security officials obtained secret documents that exposed Hamas assets worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Taskforce Harpoon had been disbanded two years before as part of an agency reorganisation.

Agents shared the documents with the Israeli government and Washington. Despite this, none of the named companies faced sanctions from the US or Israel until 2022, according to the New York Times. By then, Hamas had used some of that money to build up its military infrastructure and lay the groundwork for the 7 October attacks. Netanyahu “made the same mistake as the Saudis,” Levy said. “[Believing] you can buy quiet with money.”

To Levy, Netanyahu’s policy of allowing billions of dollars to flow into Gaza before 2023 to promote stability was doomed to failure. While the evidence in the Hamas ledgers was being ignored or underplayed, Israel’s intelligence agencies were encouraged to take the fight to Iran and Hezbollah.

The fruits of these labours were evident last year, when Israel managed to assassinate Hezbollah’s former leader, Hassan Nasrallah. Israeli agents recruited people to plant listening devices in Hezbollah bunkers, enabling them to know which one Nasrallah was hiding in before an F-15 bomber blew it – and him – up.

Israeli security forces in action.

The assassination was the culmination of a two-week offensive during which Israel remotely detonated explosives in thousands of pagers and walkie-talkies used by Hezbollah.

Each pager had a few ounces of explosives concealed within it, and the blasts sent Hezbollah militants crashing off motorcycles or slamming to the ground as they were shopping. Years earlier, Israeli intelligence had set up a shell company in Hungary, posing as an international pager producer.

This operation – a modern Trojan horse – came two years after another daring attack in which Israel killed Iran’s top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, with a remote-controlled machine gun hidden on the side of an Iranian highway.

“As a nation and an army, when the initiative is yours, you have an advantage,” Shaya said. “When you are surprised by your opponent, it’s totally different. This is a lesson we should learn. All the wars we won were wars we initiated. All the wars we had trouble with – like Yom Kippur – were when the other side had the initiative.”

As vaunted as Israel’s technical prowess is, its tactics have raised serious ethical concerns. The country has used AI extensively in the war in Gaza to compile potential targets. Many of the resulting strikes have led to heavy civilian casualties, mistaken identifications and arrests.

Success in Iran is unlikely to make criticism of the Gaza campaign recede. Last Tuesday, health officials said at least 59 people were killed by Israeli military drones and artillery fire, and more than 200 wounded, trying to get food.

For the former intelligence operatives, the rehabilitation of their colleagues is almost complete.

“It has totally recovered,” Shaya said. “But we shouldn’t pay attention to reputation. We should pay attention to how to fix our mistakes. Our enemies are not done yet.”

Photographs by IDF, Atta Kenare/AFP via Getty Images