For months, the Trump administration insisted the reason for the military buildup in the Caribbean was to stop the flow of drugs from Venezuela to the US.

Then, in recent weeks, another one bubbled up: oil.

The morning after the Venezuelan president, Nicolás Maduro, was extracted in a midnight assault on Caracas, Trump again put oil at the heart of the matter, citing Venezuela’s past expropriation of US oil assets – and his plan to take them back.

“We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies – the biggest anywhere in the world – go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure and start making money for the country,” he said. “We’re in the oil business.”

But US oil companies themselves have been strikingly silent on the nation-building role Trump has in mind for them. Experts say that restoring Venezuela’s oil industry to its former heights would take many years and a colossal amount of money – if it were to happen at all.

US-Venezuela relations have hinged on oil for more than 100 years. Companies such as Exxon, Chevron and Texaco began pumping oil there early in the 20th century. Venezuela became one of the world’s biggest producers, reaching roughly 3.5m barrels a day in the 1970s – 7% of global production at the time.

The sector went through a relatively smooth sort of nationalisation in the 1970s, in which private companies were compensated and invited to work with the new state-owned Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) as service providers, without triggering a diplomatic incident with the US.

Is the Maduro regime minus Maduro going to change? The CEO of ExxonMobil is not going to commit capital and people until there’s an answer to that

Is the Maduro regime minus Maduro going to change? The CEO of ExxonMobil is not going to commit capital and people until there’s an answer to that

Ed Hirs, energy fellow at the University of Houston

But as production slipped dramatically over the next two decades, the government decided to open the sector up to foreign investment once more, and by 1998 production was back above 3m barrels a day.

Then, in the 2000s, the charismatic socialist Hugo Chávez forced oil companies into joint ventures controlled by PDVSA and hiked taxes. Companies that did not accept the new terms were fully nationalised, with compensation well below market value.

This was at the height of the commodity boom, and at first led to a massive increase in the government take from oil sales, amounting to tens of billions of dollars a year, allowing Chávez to pour money into social spending. But mismanagement, corruption and underinvestment dragged production down. Starting in 2005, US presidents imposed a range of sanctions on Venezuela, including its oil sector.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Chávez died in 2013 and was succeeded by Nicolás Maduro. A year later the commodity boom ended and oil revenues plummeted, triggering economic and social collapse.

Today Venezuela is a small-time player in oil, producing fewer than 1m barrels a day – barely 1% of global output. Because of sanctions, most of this is sold to China through shadow fleets at cut-price rates. Only one US company, Chevron, is still involved and exempt from these sanctions, producing about 25% of Venezuela’s output.

In the meantime, the US itself rose to become the top oil and gas producer in the world, reducing its dependence on imports.

Still – on paper, at least – Venezuela still has the largest proven oil reserves in the world. Hence Trump’s ambition for US oil companies to get involved once again. But challenges abound. One is that most of Venezuela’s oil is heavy and sour, meaning it is tricky and costly to extract, transport and refine. “Crude oil ranges from, say, champagne to coffee grounds in terms of quality,” said Bob McNally, president of Rapidan Energy and a former White House adviser. “Venezuela’s is almost like sludge.”

And after decades of decay, much of Venezuela’s oil infrastructure is in ruins. “[Boosting production] is not a matter of turning on spigots,” said Ed Hirs, an energy fellow at the University of Houston. “The iron, the steel has deteriorated. It’s been cannibalised, stolen, stripped.”

Francisco Monaldi, director of the Latin America energy program at Rice University, estimates it would take more than a decade and $100bn to take production to 4m barrels a day.

Only companies such as Chevron and ExxonMobil have the kind of capital and expertise needed to make this happen. The US secretary of state, Marco Rubio, told ABC News that he was “pretty certain that there will be dramatic interest” to invest in Venezuela now that Maduro was gone. Trump said he believed US oil companies could get expanded operations in Venezuela “up and running” in less than 18 months and even suggested the government could reimburse their investment. But the oil companies themselves have been conspicuously quiet.

One reason US companies would be interested is that many of them already have refineries that were built to process the kind of oil produced in Venezuela. “Our Gulf Coast refineries love to feed on a diet of Venezuelan, Mexican and Canadian heavy crude,” said McNally.

But buying oil is one thing; investing in Venezuela is another.

“It’s cautiously tantalising,” said McNally, noting that companies were looking for new oil supply heading into the 2030s. “But with an emphasis on the cautious.”

Right now, uncertainty reigns in Venezuela. It is unclear how long the current government, led by Maduro’s former vice-president, Delcy Rodríguez, will last, let alone what the legal and political framework for any investment would be, or when and how US sanctions will be lifted.

“Is the Maduro regime minus Maduro going to continue acting the way it did, or is it going to change? The CEO of ExxonMobil is not going to commit capital and people until there’s an answer to that,” said Hirs. “And they’ve already been expropriated twice by Venezuela. Do they really want to try that a third time?”

The global oil market will also dictate the logic of any investment. Speaking to NBC News on Monday, Trump argued in favour of greater production in Venezuela to keep the price of oil down. Voters might like that, but low prices mean lower revenues for the very oil companies Trump is counting on to revive Venezuela’s oil industry.

Max Pyziur from the Energy Policy Research Foundation, an energy thinktank in Washington DC, said: “The attractiveness of pursuing investment in Venezuela from a political-legal framework, as well as from a commercial framework, right now is far diminished, if it is there at all. It’s a bearish scenario.”

One possibility is that the Trump administration’s coercive pressure means US companies can negotiate favourable deals with the Venezuelan government – though it would be years before any profits were realised.

“There may be a mismatch between how fast the Trump administration would like to see capital flow into the sector and oil production to increase, and how fast that actually happens,” said McNally. “It may be years beyond the end of Trump’s term before we see the fruit.”

After all the action over the weekend, when markets opened the price of oil barely budged. “Near-term, it’s really a nothing burger,” said McNally. “Venezuela is such a small exporter, and nothing’s really changed.”

But stocks in US oil majors did jump, perhaps reflecting a long-term bet by investors that something may actually come of Trump’s plan for them in Venezuela – or simply speculation.

“That’s just speculators thinking there might be something there,” said Hirs. “It’s Joe Sixpack on the couch saying, ‘I think I’m going to get me some oil shares.’ Good luck, guy.”

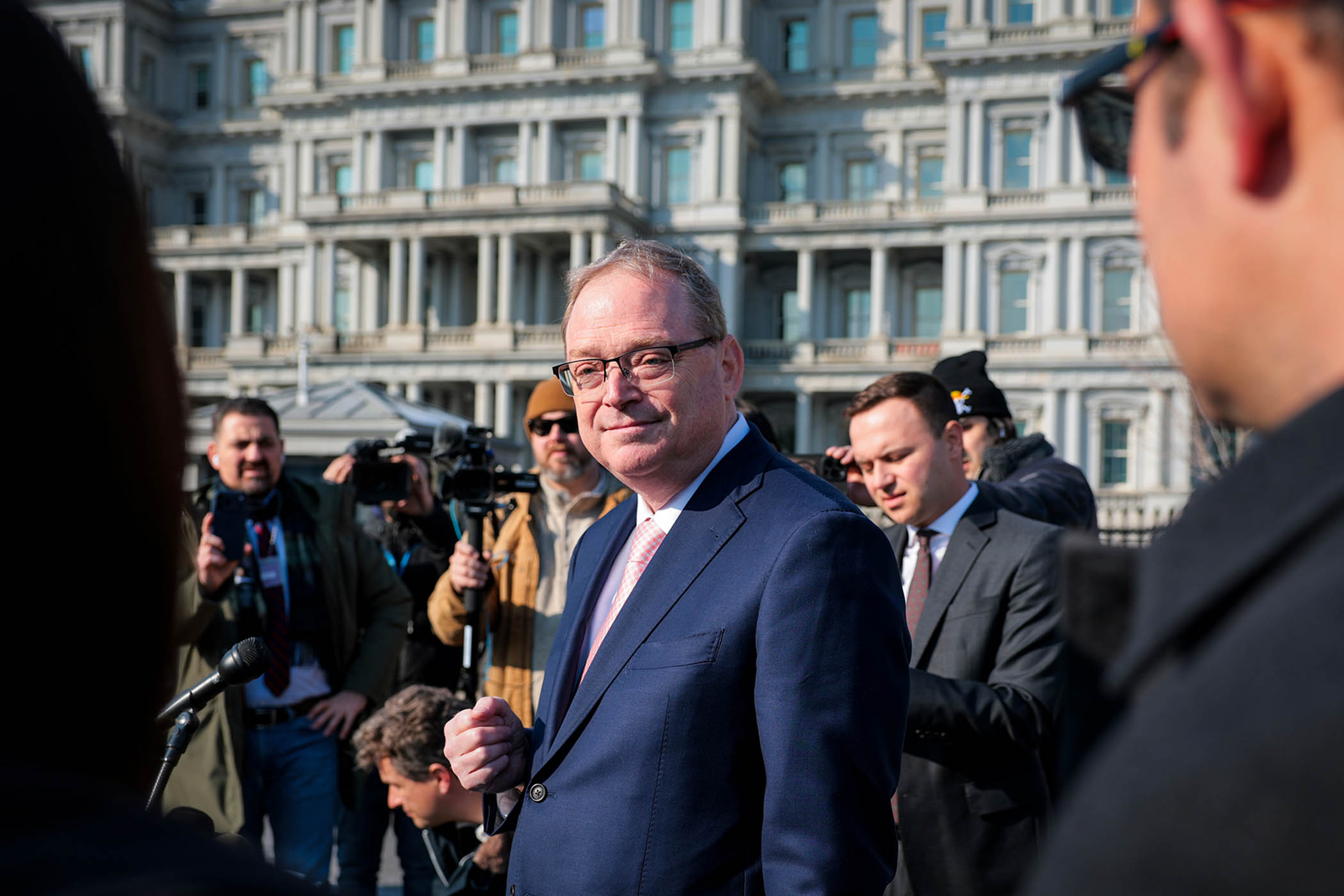

Photograph by Jose Bula Urrutia/UCG/UIG via Getty Images