Gerry Adams stared at me; an intense, piercing stare across his desk on the top floor of Connolly House, the Belfast hub for Sinn Féin, notorious for the occasional IRA interrogation.

It was autumn 1991. That summer had seen hopes for a political settlement in Northern Ireland flicker, then die. The Northern Ireland secretary Peter Brooke was trying to revive them.

For BBC Panorama I had sought an interview with Adams. Like several other journalists my relationship with Adams had been pretty fractious over the previous decade. On my arrival at Connolly House, I was summoned upstairs to his office. It was like being back in the headmaster’s study.

“Before we do this interview – if I do it – you need to tell me who told you all this rubbish about me in your last programme.”

That “rubbish” was the chronology of Adams’s IRA career set out in a 1983 documentary I produced for ITV’s World in Action called “The Honourable Member for Belfast West”. It charted his meteoric rise from humble volunteer to the “shogun” or supremo of the “Republican movement” as the IRA euphemistically called it.

Adams was at his denials again last month, this time in the witness box of the Dublin high court in a libel case he brought against the BBC. The case concerned a specific allegation in a 2016 documentary that he had authorised the execution of an MI5 informer 10 years earlier. The jury found that the BBC had not acted in good faith or in a fair and reasonable way and awarded Gerry Adams £84,000 in damages.

Although it was not the heart of that case, the question of Adams’s alleged membership of the IRA came up in court. The BBC argued that he was widely considered to have been an IRA commander during the Troubles, while Adams told the jury, under oath, that joining the IRA was “not a path I chose”. His denial of any personal involvement in attacks that cost so many lives may have been a component in the jury’s decision to set that level of damages for the harm he said the BBC had done to his reputation.

It’s the position he has maintained steadfastly to this day. Except once, I’m told.

Related articles:

When I made the World In Action documentary in 1983 the allegation to which Adams took particular exception was that in 1972 he’d admitted to a police officer that he was a member of the IRA. Six months before transmission, Adams had been elected as a Westminster MP, part of his strategy to mobilise popular support for the “armed struggle” by allowing the IRA’s political wing, Sinn Féin, to contest elections, reversing decades of abstentionism.

To make him more electable by distancing himself from personal responsibility for the bloodshed, Adams was telling any journalist who asked that he wasn’t a member of the IRA. His lawyers had even sent a long, threatening diatribe to the Irish Times demanding damages for the “monstrous libel” of calling their client the “vice-president of the IRA”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

It’s right we are reminded of the strength of evidence of his IRA membership, lest this post-truth age claims another historical scalp

It’s right we are reminded of the strength of evidence of his IRA membership, lest this post-truth age claims another historical scalp

It was the belief of special branch that due to his entry into electoral politics, Adams had relinquished his day-to-day responsibilities for IRA units as its adjutant general. My notes from the time also reflect the branch’s uncertainty as to whether he had remained on the IRA’s ruling army council. However, Adams’s once closest confidant, the late Brendan Hughes, who joined the army council in 1987, stated in a lengthy tape recorded interview in 2001 that Adams was a long-standing member and it was the firm belief of Hughes and others that Adams dominated the strategic direction of the IRA from 1983.

My documentary disclosed how Adams had used an alias Joe McGuigan when he was arrested in March 1972 and included a clip in which he said he’d been badly beaten. What Adams didn’t mention was afterwards a special branch officer who knew him had ventured into his cell and reported that he’d succeeded in engaging him in a discussion about his past, having assured him none of it would be used as evidence against him.

The day I learned this – Thursday 6 October 1983 – has stayed with me. Into the room to which I had been escorted at police headquarters arrived a senior special branch officer clasping a thick file on Adams, extracts of which were then read to me. They recorded Adams’s rise through the IRA since he’d joined as a teenager. My note records that in the privacy of his cell in March 1972 Adams had “given [special branch] his whole story, his position, everything”.

Back in 1991, so scurrilous did he regard my disclosure about his alleged admission of IRA membership, that he demanded I disclose my source as if this were a moral obligation. Of course, Adams knew very well that source protection was sacrosanct so eventually he reconciled himself to not getting my answer.

Adams with Martin McGuiness in 1985. Photo credit: Independent News And Media/Getty

His special branch file reported that he’d gone from officer commanding the IRA in Ballymurphy in 1970 to OC of the entire Belfast brigade by 1973, the most violent period of the conflict marked by deadly car bombs in crowded places. My note reads: “We have several reports that he is involved in a large number of bombings, including Bloody Friday” when 22 bombs detonated in Belfast in rapid succession killing nine and injuring 130. What the branch meant by “involved” – how directly or indirectly – is unclear.

Interned in 1973 with a short jail sentence for trying to escape, Adams was released in 1977 and the special branch reported that six months later he became head of the IRA’s new northern command. In 1978, he was arrested after firebombs incinerated 12 diners at a restaurant, which he later acknowledged was “an atrocity.” Six months later a membership charge was dropped and he was freed and in 1979, according to the branch, became IRA adjutant-general, in effect deputy to the chief of staff, Martin McGuinness. The IRA was responsible for some 300 killings between 1979 and 1982, including 18 British soldiers from two massive roadside bombs at Warrenpoint.

I observe that the dates and ranks I was given by the branch tally closely with those subsequently disclosed by former IRA comrades of Adams, most notably to Ed Moloney in his seminal A Secret History of the IRA; also, an oral account to Moloney and former IRA man Dr Anthony McIntyre given by Brendan Hughes.

Hughes claimed that Adams was his boss. “I never carried out a major operation without the OK or the order from Gerry,” he said. And Hughes carried out very many operations, from shooting British soldiers to bank robberies to raise funds for the IRA, to procuring from the US high-velocity lightweight Armalite rifles, which Hughes said he did on Adams’s instructions. In Moloney’s groundbreaking sequel, Voices from the Grave, in which Hughes is interviewed at length, there are some 560 references to Adams, a further indication of his central role in the republican movement .

By 1983 Adams was being widely credited with leading the transfer of power in the IRA from the old guard, which he blamed for its near-defeat after it agreed to a ceasefire in 1974-75. At the Sinn Féin conference in Dublin that November, he was elected president of Sinn Féin.

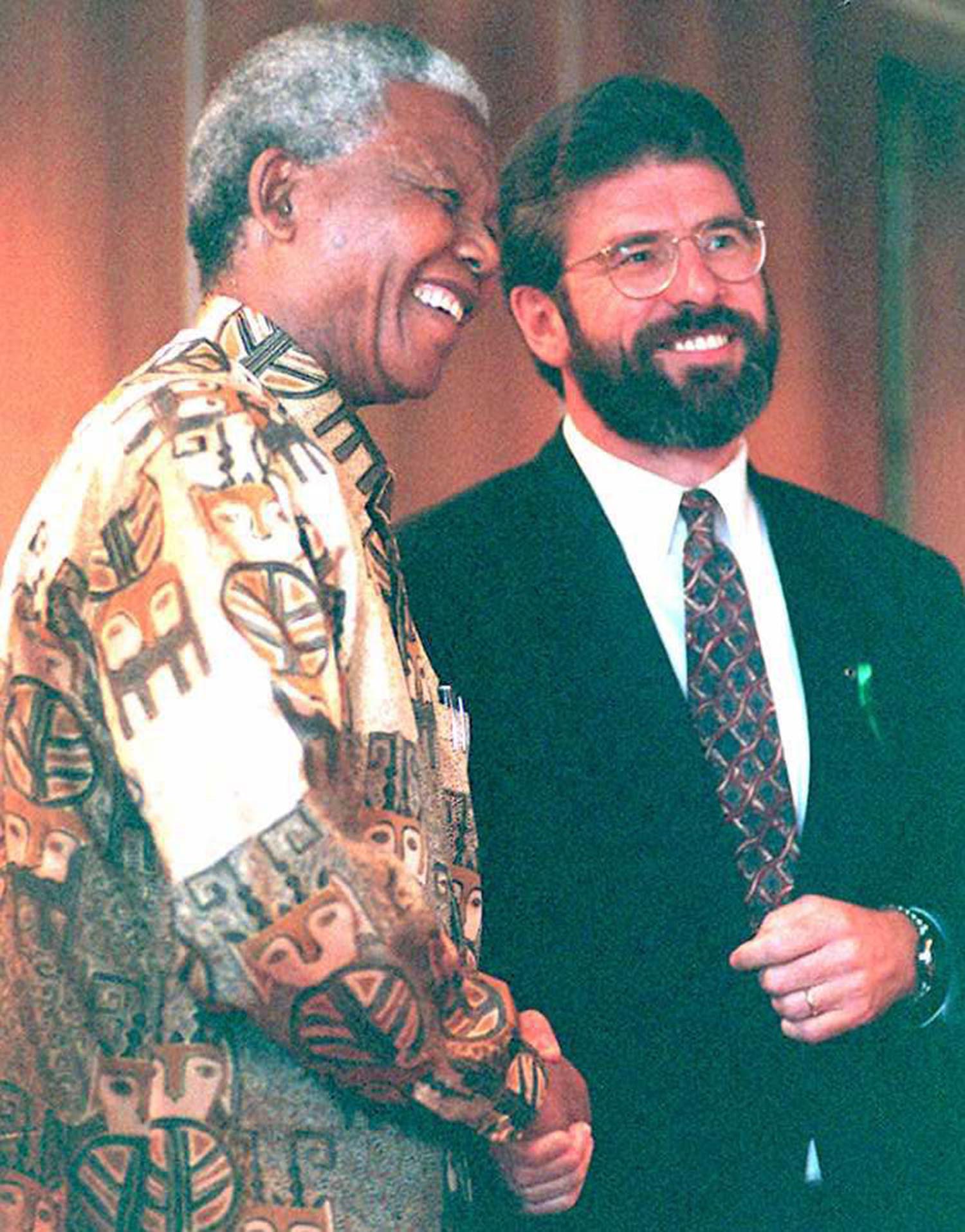

Adams with South African President Nelson Mandela in 1995 at the headquarters of the African National Congress, Johannesburg. Photo credit: Danny Hoffman/AFP

It was at that conference that we obtained corroboration for Adams’s IRA membership, which at the time I didn’t report. We covertly recorded a conversation with Adams’s right-hand man Danny Morrison. When I asked Morrison if Adams’s increasing foray into constitutional politics meant he was becoming militarily “doveish”, he pushed back: “Where do you think we came from?” We were also the first to disclose that while in jail Adams had penned a series of columns under the alias “Brownie” in which he wrote “Rightly or wrongly I’m an IRA volunteer. The course I take involves the use of physical force…” – again, something Adams strongly denied in the witness box.

So following Adams’s victory in court last month, it’s right that we are reminded of the strength of evidence of his IRA membership, lest this post-truth age claims another historical scalp, especially since his persistent denials have been characterised by a haughty “how-very-dare-you” umbrage. As the writer Howard Jacobson says, alarm bells ring when a politician stands haughty upon his honour.

“Is it not true you have a decisive voice in the activities of the IRA?” BBC Panorama’s Fred Emery asked Adams in 1982 after the first of his many election victories, this time to the Northern Ireland assembly. Adams dismissed this as “an impertinent question”.

Asked by the American NBC network in 1983 if his move into constitutional politics meant a reduction in violence, with no hint of irony Adams replied: “Well, that’s a question you’ll have to put to the IRA.”

To the faithful, it was a different story. At that year’s commemoration of Wolfe Tone, Irish republicanism’s founding father, knowing cheers and laughter greeted Gerry Adams when he welcomed “Friends... my fellow gunmen and gunwomen.”

Questions of morality are very difficult and vexed ones for all of us

Questions of morality are very difficult and vexed ones for all of us

Gerry Adams, 1996

Adams regards himself as a deeply moral individual, unable to “get through life without being prayerful” and he “like[s] the sense of there being a God”. It is true that he has sometimes sounded intensely regretful for civilian deaths in IRA atrocities, and yet he has also hedged: “Questions of morality are very difficult and vexed ones for all of us,” he said in 1996.

Yet in 1987 he had no difficulty in rationalising on TV the brutal execution of an alleged IRA informer Charlie McIlmurray by telling his West Belfast constituents that “Mr McIlmurray, like anyone living in West Belfast knows, that the consequence of informing is death.”

Last month in the Dublin high court, when asked about his attendance at the funerals of IRA members, he responded: “You’re trying to persuade this jury I had no reputation whatsoever because I attended funerals?”

It was more than mere attendances. Adams carried the coffins of multiple IRA volunteers who had terrorised the public and gave many graveside orations. To mark his libel victory over the BBC, Adams put out a blog. Its title, “Putting manners on the BBC”, was the kind of Brit-bashing that still lands well within republican grassroots.

And here’s the puzzle: there was never any need for Adams to deny his involvement in the IRA. He could simply have said “no comment”.

Instead we’ve had decades of pious moralising about the sanctity of the “armed struggle” but with claims of no personal involvement in it.

True, under his influence, the IRA wound down its murder machine, Adams having recognised Irish reunification was more achievable by going constitutional. Only he and the God he prays to will know whether he was gripped by more of a tactical imperative than a moral one.

One explanation might be that had Adams taken the “no comment” line rather than outright denial, he would have lost the kudos of the many world statesmen and notables who’d vouched for him. They’d have egg on their faces.

And one thing is clear: once the BBC had broadcast a serious allegation it couldn’t prove but, given Adams’s past, considered in the public interest to air, he seized the opportunity of rewriting history as victors do. “For many years when I was wrongly represented in sections of the media, my legal advice was consistently not to sue for libel,” his victory blog explained.

Fortuitously for Adams, the BBC signal reached across the Irish border allowing him to achieve his ambition by suing for libel in Dublin, where not only would the judge not allow evidence to be introduced of his involvement in the IRA; he also required the jury to adjudge Adams’s reputation as it stood in 2016 exclusively within the republic. The selected jury was relatively young, their lived experience of the conflict in the distant north confined to its final phase heading for peace, the worst of the bloodshed behind them.

A leading American vouchsafer for Adams, former Congressman Bruce Morrison told the court that he had a reputation as someone whose “word could be taken seriously and could be relied on”.

In delivering peace, that is clearly true. And it is the peacemaker in Adams that the jury appears to have bought into, more than the peacetaker. In a statement sent to The Observer, Adams’s lawyer said simply: “My client has consistently rejected over many years all claims that he was a member of the IRA.”

To parody Ireland’s WB Yeats, at the high court in Dublin last month, a terrible beauty was born.