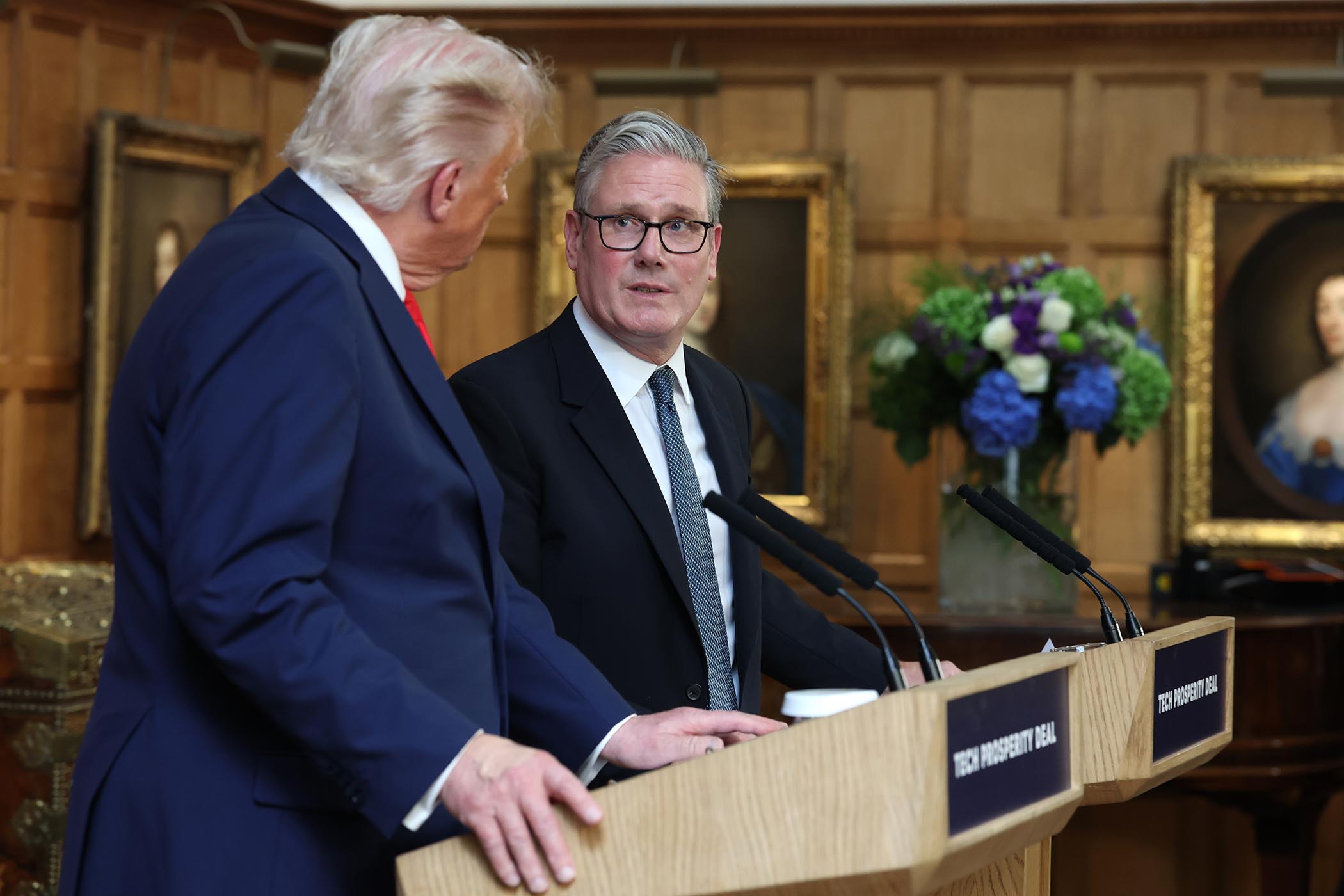

Portrait by Tom Pilston for The Observer

Keir Starmer says the thing he misses most as prime minister is taking long, solitary hikes in the countryside. “Going for a walk on your own and clearing your head, being out there with nature, is something I really enjoy. The peace, quiet, taking in a wider world – I've always loved it,” he says. “I don't moan about what comes with being prime minister. I want to do it, I love doing it, it’s a great privilege and therefore I don’t list all the various things that can no longer be done. But that one…”

He pauses. “Theoretically, I can go for a walk but the police team would come with me. I don’t feel that when they’re walking just behind me I can ignore them and therefore I start talking to them. It’s not the same as going for a walk on your own.”

We are in Cardiff where Starmer had hoped to take me on a ramble across the Welsh hills near his grandmother’s home, or a stroll where his wife, Victoria, went to university. As if to prove his point, security concerns and rain mean we have to stay inside the children’s centre he is visiting. But it is the conversation that counts, so we make the most of our walk around the corridors and classrooms.

Norman Tebbit, Margaret Thatcher’s party chairman, used to say that No 10 is the only building in Britain where the windows are smaller inside than outside because prime ministers so quickly get detached from reality in the Downing Street bunker. Starmer insists he is determined to cling to as many aspects of normal life as possible. “It is hard, and you have to fight for it. Different prime ministers do it in different ways. The way I’ve done it is keeping Vic and the kids pretty insulated from this life. The kids [a boy and a girl, aged 17 and 15] go back to north London, to their old life every day; they’re in the same schools, the same environment. Vic still works in the NHS. We just live in a different location.”

He has a “strict rule” of “no working meetings” in the Downing Street flat. “When I go into the flat, I’m Dad. Their main job, my two children, is to amuse themselves by laughing at me.” He still occasionally plays in his Sunday league football team – “when you get on the pitch it doesn’t matter what you do for a living”. And he returns every few weeks to the barber who has cut his hair for 20 years. “When our little boy was two, I took him there for the first time, I had to hold his hand because he was so scared. Now he’s six foot one. We go together and sit side by side.”

‘The young have been collateral damage for past governments’ failure – I want to turn that around’

‘The young have been collateral damage for past governments’ failure – I want to turn that around’

Increasingly, the public and private worlds are colliding. Earlier this year, the Starmers were profoundly shaken by the “fire-bombing” of their north London house. Now their new home could be under threat from mutinous Labour MPs who are plotting against their leader. The voters are disillusioned. One poll last week put Labour in fourth place behind Reform, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats. In Wales, Starmer’s party is heading for annihilation at next May’s Senedd elections. On the train to Cardiff, I message a minister to ask what I should ask the Labour leader. The reply: “Does he understand how viscerally unpopular he is?”

The clash between the desire for normality and the deep abnormality of being leader is symptomatic of a wider conundrum. Even though he is one of the most quoted and photographed people in Britain, Starmer is still a riddle for many. He is a working-class lad with a knighthood, a technocrat who has reached the pinnacle of politics, a north London human rights lawyer who is introducing the toughest immigration laws for a generation, and a staunch pro-European who refuses to revisit Brexit.

The son of a toolmaker who grew up in a pebble-dash semi in Surrey is often described as “ordinary” but his life has been extraordinary, with a traumatic childhood overshadowed by his mother’s debilitating illness and his father’s detachment. “My dad had no emotional space for us children,” he says. “He saw his job as ‘I go out and earn my living, I bring it home’. It wouldn’t have crossed his mind that, if he had spent more time with [us], that might have been something he would have enjoyed. He invested such emotional energy as he had in my mum. I was determined to be different with our kids.”

Voters – and Labour MPs – struggle to understand what drives Starmer or why he wants to be PM. So how does he articulate it? “I came into politics to change the lives of millions of people. I suppose if I was to reduce that down, it would be a focus on young people,” he replies. “Young people have been collateral damage for the failure of past governments and I intend to turn that around.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The decision to end the two-child benefit cap, announced in the budget, will be followed by a “youth guarantee” of work or training and thousands more apprenticeships. “There are plenty of people held back because they’ve grown up in poverty, or they’re working class, or they’ve been overlooked, who theoretically have the chance but don’t really have the chance,” Starmer says. “There’s a sense of ‘that’ll do’. Well, it won’t do.”

The prime minister points to his own family. “I came from a working-class background. I was the first to go to university, did law, had a good career as a lawyer, became a public prosecutor, leader of the Labour party and now prime minister. What better evidence could you have of social mobility in Britain? I tell that story because I hope other children might think, ‘perhaps I can do it’. When I was growing up, I didn't ever think I'd be Prime Minister.”

But his own experience is “more the exception than the rule”, he suggests. “Within my family, that didn’t happen to my two sisters, it didn’t happen to my brother. And my family reflects Britain. For every one person that does get through the gate, there are plenty who don’t.”

Aides say Starmer is most animated when meeting young apprentices in shipyards or nuclear power stations. “We still elevate going to university over doing an apprenticeship and, while we continue to do that, we are sending a message to those doing apprenticeships that somehow they’re not as highly regarded and they should be.” His brother, who died last year, struggled with learning. “My mum and dad… instilled in me ‘you’re not doing any better than your brother is, Keir’.”

Does he feel guilty? “No, I feel defensive, protective. I don’t like to display anger and I don’t often, but when people say someone is thick, something goes through me. I hate it because they’re talking [about] my brother. And he wasn’t thick.”

For the first time, the cabinet is entirely state educated and many ministers have, like Starmer, overcome adversity in their early lives. “It does make a difference,” he says, “because having a point of connection is important. You need to have people in your mind’s eye – not a policy, graph, a set of statistics but the people whose lives are going to be changed.”

We walk down a corridor, past pictures of children jumping in puddles, and turn into a classroom. Angela Rayner, who grew up caring for her bipolar mother and left school, pregnant, at 16, is “the best social mobility story this country has ever seen”, Starmer says. Does he miss her? “Yes, of course I do. I was really sad that we lost her. As I said to her at the time, she’s going to be a major voice in the Labour movement.” Will she be back in the cabinet? “Yes. She’s hugely talented.” He thinks both Rayner and the chancellor, Rachel Reeves, have suffered from misogyny at Westminster. “All politicians get quite a lot of abuse these days but for women it’s always worse.”

Starmer says ensuring young people fulfil their potential is his “moral mission” but government policy does not always match the rhetoric. The curriculum and assessment review, which should have been the chance to reinvent the education system, was woefully unambitious. “I think we can do more, frankly, and I think we should do more.”

And the budget, which some wanted to redistribute resources between the generations, ended up once again favouring the old. The Treasury has even declared that pensioners will be exempt from income tax if the state pension tips over the threshold, while younger workers, earning precisely the same amount, will still have to pay.

“I don’t think you should trade off young people and pensioners,” Starmer insists. Surely the increasingly unaffordable pension triple lock has to go after the next election? He does not want to be drawn on what happens in the next parliament “but your challenge is a good one,” he says, “which is to make sure we’ve got a clear enough path with resources, funding and ambition for young people to go as far as their talent will take them.”

Then there is Europe. Starmer is determined to reach an agreement with the European Union to bring in a youth mobility scheme. “We’re looking at the size of it, the duration of it,” he says, “but the principle that young people should be able to go and study and work and enjoy time in another country in Europe is a really important one.” Some believe he should go further. Minouche Shafik, his economic adviser, is among those urging him to boost economic growth by entering into a customs union. Starmer insists there is another way. “I’m having discussions with all our EU partners about how we can be closer, and we’re making real progress. They are not saying, ‘join the customs union’.”

I ask him five times whether he still believes the UK will not rejoin the EU in his lifetime, as he said in the run-up to the election last year. He conspicuously fails to repeat the claim. “We’ve stopped having the discussion about whether we should go backwards and pick over Brexit” is the closest he gets to a reply.

The prime minister insists that “the battles coming up in politics” are bigger than him or his party. “They’re about who we are as a country,” he says. “We are at a political fork in the road, the like of which we haven’t seen.

“We’ve had Labour versus Tory at every election since the war. I’ve always wanted a Labour government but I’ve never worried about the future of our country under a Tory government. With Reform, I worry about what will happen to our country in terms of tearing our communities apart. Once you say that diverse communities aren’t British, that reasonable, compassionate people aren’t part of who we are, and that we don’t want to look after each other, and that only points of division count, you’re going in a different direction.”

He is almost as rude about the Greens. “They’re anti-Nato at a time when the world is more volatile than it has ever been. The Green party thinks it’s all right to sell drugs and there should be no restrictions. So somebody could sell drugs outside my children’s school but, if you’re a landlord, it should be unlawful. That’s nuts. They’re dangerous.”

The stakes could not be higher. Downing Street is clear that if Starmer faces a leadership challenge, he will fight it. Victoria is “always there to defend”, he says. “She is a complete rock and she’s got brilliant instincts. We do talk things through.”

But his own personal ratings are among the worst of any prime minister. If he thought that him staying on as leader would make a Farage premiership more likely, would he stand aside?

“When I took over the Labour party, everyone said to me, ‘you’re not going to be able to change the party’. We ignored that and carried on. Then they said to me, ‘you’re not going to be able to win an election.’ We got a landslide Labour victory. Now, 17 months into a five-year Labour term, they say ‘you’re not able to change the country’.

“Every time we’ve been in this position, we’ve defied them. And that’s what I intend to do.”

He says his mother taught him to always walk towards the next challenge. “Every time she was knocked down, she would get back up. However hard that was for her, even when it took her months and months to get back on her feet, she said, ‘I’m going to walk’. I carry that inside me.”