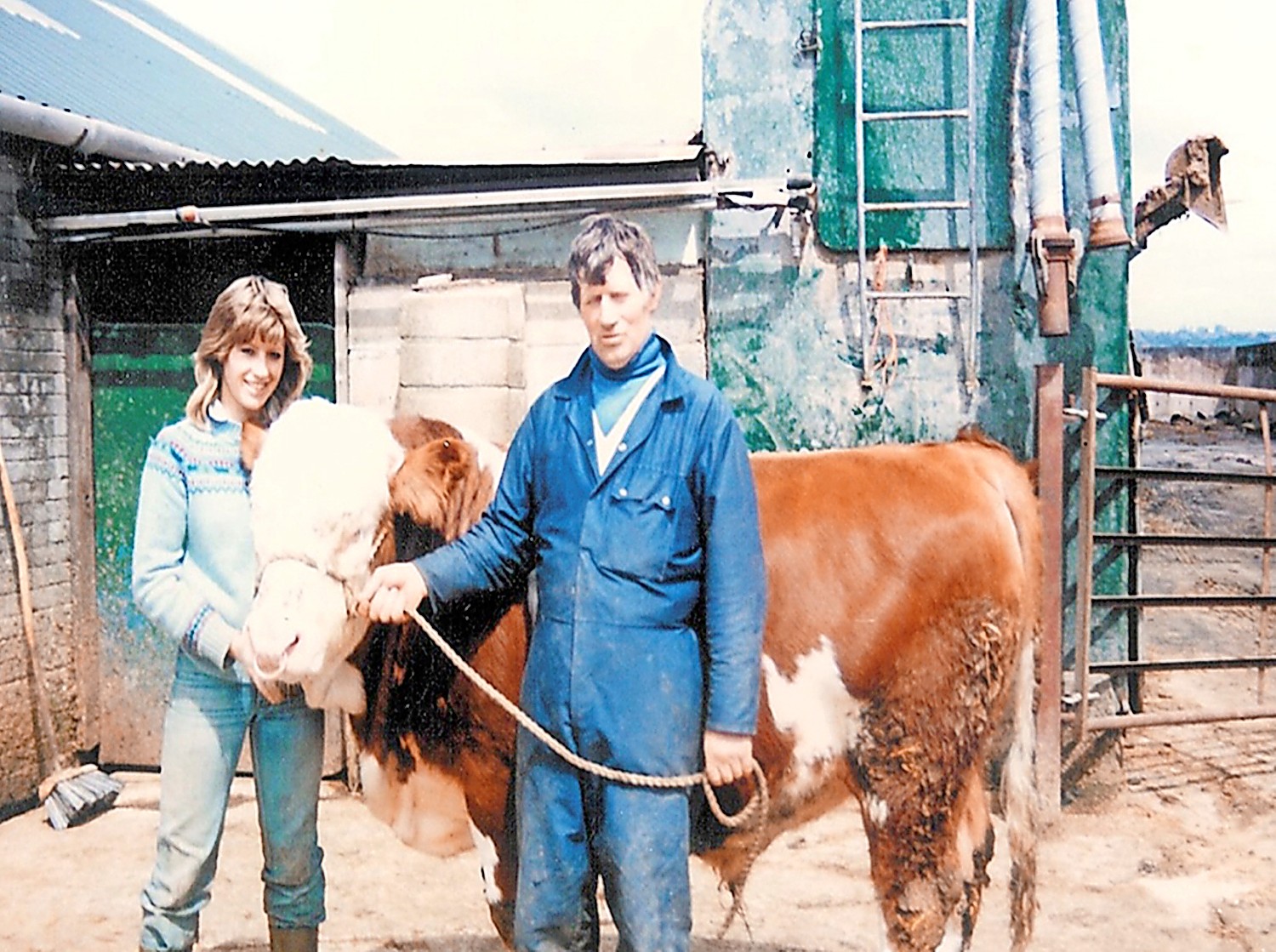

As a child, Julie Plumley remembers seeing her father spraying weedkiller on his farm in Dorset, with his arms bare and no mask on his face.

She would work at his feet pulling out weeds as he sprayed the land from a container strapped on his back, with the breeze blowing the acutely toxic spray through air. John Stockley was later diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and always believed the weedkiller – called paraquat – may have been involved. He died in 2017.

Syngenta, the Chinese-owned manufacturer of paraquat, has moved in a recent court filing to settle claims in the US over allegations that farmers and agricultural workers developed Parkinson’s disease and kidney disorders after exposure to paraquat. The firm has said litigation can be time-consuming and “distracting”, stating that despite the move to settle there is no merit to the allegations.

Paraquat was banned for use in the UK in 2007, but Syngenta is still permitted to make weedkiller at its plant in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, for export. Campaigners are calling an immediate ban on its UK production.

Plumley, 62, who lives near Sherborne, Dorset, founded the charity Countrymen UK to provide support to people like her father. She said she had seen several cases over the years of farmers and workers who have developed Parkinson’s after using paraquat, with no family history of the condition.

These cases included one man who used the herbicide to clear weeds on railway tracks and another farmer who worked with her father and had also regularly sprayed paraquat.

“These people have been the rocks of their family and suddenly everything is taken away,” she said. “I felt my dad was stolen from us.”

She said she was “ashamed” the product was exported from the UK despite a ban on its use in the country because of its toxicity. She said: “I can’t understand how this can happen. We’re not allowed to use it here, but we’re producing it for other people.”

Plumley said she welcomed any payments to farmers and agricultural workers in the US, but there should be a wider compensation scheme. She said more research was required to establish the incidence of Parkinson’s disease in farming areas in the UK.

‘These people have been the rocks of their family and suddenly everything is taken away’

‘These people have been the rocks of their family and suddenly everything is taken away’

Julie Plumley

Paraquat was first manufactured in 1962 by the British chemical giant Imperial Chemical Industries. Its use is now banned in more than 50 countries, with the US Environmental Protection Agency warning users that “one sip can kill”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The plant in Huddersfield employs more than 450 people. In March it marked the first production batches of a new insecticide after a £50m investment, hailed by investment minister Poppy Gustafsson as a “vote of confidence in the UK economy”.

A number of scientific studies have found an association between paraquat and Parkinson’s, but there is no conclusive evidence of a causal link. Studies have shown agricultural areas often have higher rates of the disease.

Figures obtained by Greenpeace Unearthed found Syngenta in the UK exported 2,771 tonnes of paraquat in 2023, with all exports going to the US. Greenpeace UK chief scientist Dr Doug Parr said: “As Syngenta prepares to settle thousands of lawsuits with US farmers and more European countries ban exports of hazardous pesticides, it’s time for the UK government to end this toxic trade once and for all.”

The Pesticide Action Network UK said paraquat was one of the “most deadliest pesticides” still in production and it wanted to see a global ban on its use.Syngenta faces 5,800 lawsuits in the US. Lawyers involved in the case filed a motion to stay the case on 14 April 14 after signing an agreement intended to resolve a large tranche of the cases.

Sygenta said in a statement: “Syngenta has settled certain claims ... related to paraquat. Syngenta believes there is no merit to the claims, but litigation can be distracting and costly. Entering into the agreement in no way implies that paraquat causes Parkinson’s disease or that Syngenta has done anything wrong. We stand by the safety of paraquat.

“We have great sympathy for those suffering from the debilitating effects of Parkinson’s disease. However, it is important to note that the scientific evidence simply does not support a causal link between paraquat and Parkinson’s disease.”

The company says it considers there are flaws in research suggesting an association between paraquat and Parkinson’s disease. It says Dr Douglas Weed, an epidemiologist with no ties to Syngenta, has reported “there is no compelling scientific argument for claiming that an association exists much less a causal association”. The firm says more than 750 firms around the world are registered to sell paraquat, a generic herbicide; it was an essential tool to improve soil health; and that it was was safe when used as directed.

The UK’s toxic pesticide exports

In just one year, the UK exported nearly 8,500 tonnes of pesticides banned on farms in this country.While France and Belgium prohibit the export of pesticides banned across Europe, the UK still allows such products to be made in Britain and sold to foreign markets.

In 2020, Baskut Tuncak, then a United Nations special rapporteur, warned of the “double standards” of countries that allow the trade in chemicals banned in their territories. An investigation published by Greenpeace Unearthed and the NGO Public Eye in December found that in 2023 8,489 tonnes of pesticide banned on British farms were exported from the UK. Of those, 98% were made by Syngenta, which is based in Basel, Switzerland, and owned by a Chinese state-owned enterprise.

The export of hazardous chemicals is regulated by the Health and Safety Executive under the Prior Informed Consent Regulation. For certain pesticides, such as paraquat, the explicit consent of the country is required before export.

A government spokesperson said: “We take our trade and international obligations for human health and the environment very seriously. This is why the UK goes beyond international standards for paraquat exports, requiring explicit consent from the importing country before any export can take place.”