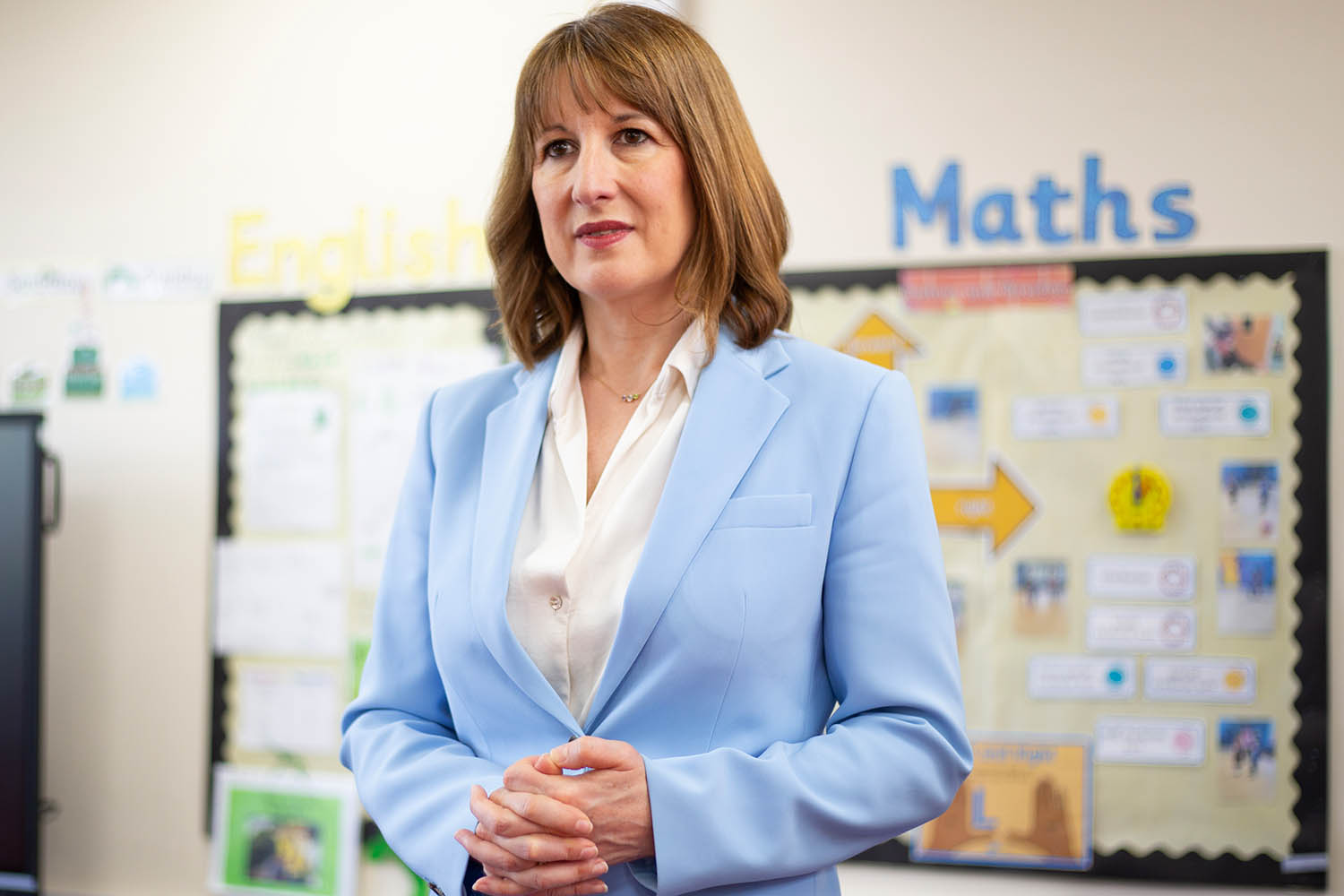

Who does Rachel Reeves have in her “mind’s eye”, as the prime minister put it, ahead of her first spending review this week?

“I think of the young people growing up in my constituency,” says the chancellor and MP for Leeds West and Pudsey. “I did really well at school but there were loads of girls who didn’t fulfil their potential.

“I don’t think that a young person growing up in Armley in Leeds, or Rochdale, has the same opportunities as a young person growing up with middle-class parents who have money to pay for the extra music lessons, sports, tuition, or even a bedroom where you can do your homework, or the security that you will be living in the same place for a long time. I want young people to have the opportunity to fulfil their potential, wherever they’re from, whatever their background. That’s what really matters to me.”

If Gordon Brown’s driving purpose as chancellor was to reduce child poverty, and George Osborne had the Northern Powerhouse, Reeves, the daughter of teachers, defines her mission as education.

Although last week the chancellor toured the country announcing billions of pounds for public transport as part of a £113bn capital expenditure splurge, this week, along with settlements for the NHS and defence, she will allocate an additional £4.5bn a year to schools. The Treasury says this will take per pupil funding for five to 16-year-olds in England to the highest level it has been.

The government has already announced plans to expand the number of children who receive free school meals and the prime minister has made clear he wants to reverse the two-child welfare cap to drive down child poverty. In an interview with The Observer, Reeves says her personal and political priority will always be improving life chances for disadvantaged young people.

‘I don’t want my mum or someone else’s mum to be paying more tax than they need to’

‘I don’t want my mum or someone else’s mum to be paying more tax than they need to’

Rachel Reeves, chancellor

“This is not about just getting children a pound above the poverty line. You want to give people real opportunities. Of course, that’s about good schools but it’s about more than that, it’s about good housing, good transport, it’s about having facilities in the local area, all the things that some people take for granted but are not the reality for everybody.”

Reeves, 46, who has two young children, insists that she cares as much about the “soft infrastructure” of nurseries and school breakfast clubs as the “hard hat” projects favoured by her predecessors. “What is the biggest thing that stops women from fulfilling their potential? It is often not having good childcare. If we want to boost productivity and participation in the labour market and make the most of talent everywhere, helping women get back to work is absolutely crucial,” she says.

Related articles:

“I do think I approach it differently. We all bring everything in our stories and our backgrounds to our jobs. I’m the first female chancellor but I’m also someone who went to my local state school from a pretty ordinary background. My parents weren’t poor but they weren’t well off. They got divorced when I was quite young.

“My mum kept all of her receipts, she went through them with her bank statements because we did not have money to waste. I take that approach. The Treasury’s money is taxpayers’ money and I don’t want my mum or someone else’s mum to be paying more tax than they need to or not getting value for money. That’s very deeply ingrained in me.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Almost a year into the job, Reeves is under attack from the right for raising taxes and from the left for cutting welfare. One side criticises her for splashing the cash, the other blames her for returning to austerity-lite. The economic growth she promised to deliver has failed to materialise and the cost of living crisis continues to bite. Her honeymoon with business is over.

“It’s a problem,” one senior Labour figure says. “We’ve got a situation where business has been hammered on national insurance costs, hammered on energy prices and hammered on labour market reforms.”

The chancellor boxed herself in to demonstrate economic credibility before the election. Now cabinet ministers, who have been fighting furiously to defend their budgets ahead of the spending review, complain that she is too single-mindedly focused on her fiscal rules.

One highlights the decision to suddenly impose an additional £500m cut to incapacity benefit in the spring statement after the Office for Budget Responsibility downgraded its growth forecast. “We should have been making a moral argument about welfare reform but instead it became all about saving money.” The cut to winter fuel allowance – the chancellor’s first big announcement – is expected to be reversed this week. “She’s been captured by the Treasury, it’s all about balancing the books,” a former minister said. “There’s a lack of imagination.”

One radical idea proposed to the Treasury, and being discussed, is to include “human capital” projects which produce a high return on investment – such as early years education or public health measures – in the definition of capital spending, making it easier for the chancellor to boost funding for these services.

A senior Labour figure says: “Rachel is very bright, quite tough, people like working with her. As ever, women are judged more harshly than men. They talk about her hair and clothes, which Gordon Brown or George Osborne never had. But the problem with both Rachel and Keir is neither of them can draw pictures. Their speeches are really abstract, they don’t bring it alive.”

Jeremy Hunt, the chancellor’s Conservative predecessor, who is in regular WhatsApp contact with her is more forgiving. “Compared to many Labour politicians she’s got very sensible instincts,” he says.

“She arrived as chancellor and found there were pressures on the public finances. She thought it was all the terrible Tories but I think she’s beginning to realise that’s the job.

“Just this week she committed to a defence review that’s going to cost 3% of GDP but only put up 2.5%. Trying to make ends meet is part of what every chancellor does.”

Paul Johnson, Institute for Fiscal Studies director, thinks Reeves, a former Bank of England economist, is a natural fit for the Treasury. “She feels a bit like a chancellor from central casting but to some extent that’s a good thing. Kwasi Kwarteng [Liz Truss’s chancellor] was against Treasury orthodoxy and look where that ended. The orthodoxy is the orthodoxy because we’ve learnt over decades what works and if you stray too far from it, you get disaster.”

But he warns that, with President Trump causing havoc in the global economy, it is looking increasingly likely that Reeves will have to raise taxes in her autumn budget. “She’s not looking like a lucky chancellor.”

Reeves, who describes herself as a “girlie swot” and a “worrier”, must hate the uncertainty created by an unpredictable US president. But, having coined the term “securonomics” – by which she meant the government should intervene to protect households from economic shocks – she insists she is prepared for the worst.

“In an age of insecurity you need to do things differently. Where things are made and who makes them matters. We are trying to build an economy that can better withstand shocks because shocks are coming more quickly,” she says.

“Every week in my weekend reading I have a pack of all the different initiatives going down to quite a micro level – solar farms, wind farms, data centres – and I go through them say ‘OK is there enough water for this housing development? Can we get a grid connection soon enough for this data centre?’ We are focusing on growth in a way the Treasury has not done for a long time.”

When Reeves was a junior chess player, her trademark move was the Sicilian Defence, a particularly aggressive opening. She won her first match when she was seven and became national champion at 14. As she competed in tournaments all over the country, she was often patronised by privately educated boys.

She remembers being drawn against one whose friend told him: “Lucky you, you’ve got a girl. You’ll win no problem.” She was determined to win, and did. “I have always had a thing about proving I’m as good as anyone.”

The focus on education in the spending review could give her the human narrative she and the government need to cut through to the voters. “I often get stopped by women who are really proud that we’ve smashed the glass ceiling. People say ‘I showed my daughter you on the telly and said: if you work hard at maths, you could do a job like that one day’.”

Photograph by Richard Saker/The Observer