The rash Lucia Magee had on her hand was barely noticeable. “It was really just redness,” William, her father, said. “If she hadn’t been a twin, we might have just concluded she had red fingers.”

But the absence of the rash in Lucia’s identical twin sister, Isabella, made their parents suspicious.

Two years later, the five-year-olds have formed an important part of groundbreaking research at Great Ormond Street Hospital (Gosh) and University College London (UCL) that may help scientists unlock treatments for several illnesses, including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

What the Magees now know is that Lucia has a rare muscle disease, one her genetically identical twin sister does not have.

The family had not heard of juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM), the illness Lucia was eventually diagnosed with. Few people have. It’s a rare autoimmune disease that is detected in about two in a million children each year. After the rash appears, it starts weakening muscles, so children seem more tired than usual.

“The reason it’s so serious is that a child can become extremely weak to the point where they can’t swallow properly,” said Lucy Wedderburn, a professor at UCL and a paediatric rheumatology consultant at Gosh.

If the condition is left untreated, it can harm the brain, lungs and gut, which, Wedderburn said, could even burst. For some children, JDM is fatal.

“As parents, naturally, when this sort of thing happens, you start googling,” William Magee said. “And it freaked us out – stories of children waking up and being unable to move. But we were fortunate that we somehow stumbled across the right doctors to get a diagnosis.”

Related articles:

The standard treatment for JDM is a course of steroids combined with other drugs to stop the body’s immune system from attacking itself. This is enough for some children to recover completely, but for others, the disease returns.

Wedderburn and her colleagues are trying to find out why. They are working with 705 families that have experienced JDM, in a group funded by Versus Arthritis, Myositis UK, Gosh Charity, the National Institute for Health and Care Research, the Chernajovsky Foundation and the George Bessell DFM Trust.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

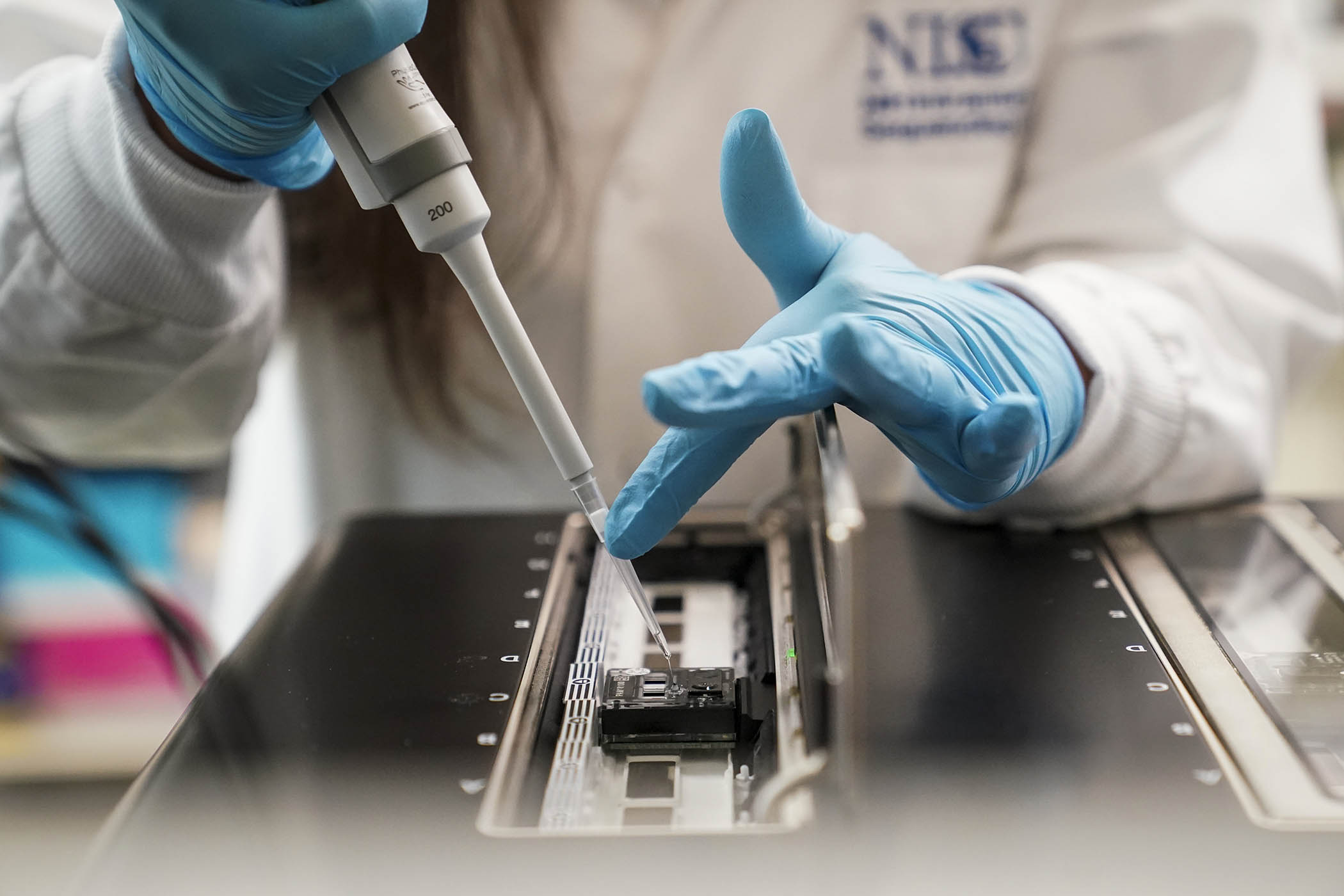

A new gene technique known as spatial transcriptomics has revealed part of the answer. The method is one of several developed in the past decade that enable biomedical researchers to examine single cells. The team used it to look at the muscle cells of Lucia and other children to identify which genes were active. They discovered a new issue: the cells’ mitochondria were not working properly.

“Mitochondria are the energy-producing components of all cells in the body,” said research fellow Meredyth Wilkinson, who led the project. “What was striking was a dysfunctional signature of some genes that were related to the energy output from mitochondria. It really opens up a body of evidence that shows we need to be targeting these mitochondria.”

Discovering that the mitochondria were not providing energy to the children’s muscles helps explain why they became weaker.

Mitochondria are a biological curiosity. Scientists believe that they may have been independent organisms that were absorbed, during the course of evolution, by other cells. They have their own DNA, separate from the nucleus in human cells, which is only transmitted through the mother.

This may explain why Lucia has JDM but Isabella does not.

The environment impacts on your genes and how they work. Food, infections, your gut. Gradually you acquire differences, especially in your immune system

The environment impacts on your genes and how they work. Food, infections, your gut. Gradually you acquire differences, especially in your immune system

UCL professor Lucy Wedderburn

“For me, the reason it’s so interesting is that the mitochondria, even in identical twins, won’t be identical at the very first cell split,” Wedderburn said. When a fertilised egg splits into two, the mitochondria are divided between the eggs.

That means it is possible that Lucia received mitochondria from her mother that her twin sister did not, and her mitochondrial DNA are responsible for her JDM.

Alternatively, something may have happened later on, with Lucia encountering something that triggered the disease while her sister did not. “The environment impacts on your genes and how they work,” Wedderburn said. “Food, infections, your gut. Gradually you acquire differences, especially in your immune system.”

Mitochondrial damage has been linked to other diseases. One of the genes studied during the research was PRKN, which is responsible for making a protein called parkin, which can cause genetic Parkinson’s disease, Wedderburn said.

“There will be very rare neurological diseases that start with a problem in a mitochondrial gene. And probably many other diseases, such as Alzheimer’s. There’s interest in this kind of interaction right across lots of diseases.”

The aim now is to establish whether existing drugs might be able to treat the mitochondrial dysfunction in JDM. One candidate is N-acetyl cysteine, or Nac, which is used to reverse the damage caused by taking too much paracetamol. The next stage for Wedderburn and Wilkinson is to develop a blood test that can detect the dysfunction.

The Magees are hoping Lucia will not need it. So far she has responded well to treatment, which includes steroids and plasma transfusions of intravenous immunoglobulin.

“Six months into treatment, things have started to quiet down,” William Magee said. “Lucia is now essentially symptom-free. We hope to stop the hospital visits some time next year.”