The actor Eddie Marsan is an avid reader who studies complex texts to learn his lines. But when he was growing up on an east London council estate, the first time he picked up a book for pleasure, his father grabbed it and threw it across the room.

“The things that held me back were cultural,” he says. “In my experience, for the white working class, because they’d experienced poverty over generations, everything was short term – economically, educationally, morally.”

The wider impact is stark. White boys who are eligible for free school meals, like Marsan was, consistently underperform in education. Only a third in England achieved a grade 4 or above – the equivalent of a pass – in their English and maths GCSEs in 2023. This means almost 30,000 failed.

By contrast, 60% of Asian boys and 53% of Black boys on free school meals passed the crucial educational hurdle. Among white working-class girls eligible for free school meals, the figure was 38%. The total rate across all students was 65%.

Only 14% of white British boys on free school meals go on to university compared with 68% of male Chinese pupils from a similar financial background, according to social mobility charity the Sutton Trust.

“The performance of white working-class boys is really worrying,” says one senior source at the Department for Education (DfE). “There’s something not working. You have to recognise the successes of the system but be open and honest with each other about where we’re failing, and that’s a group where it really jumps out.”

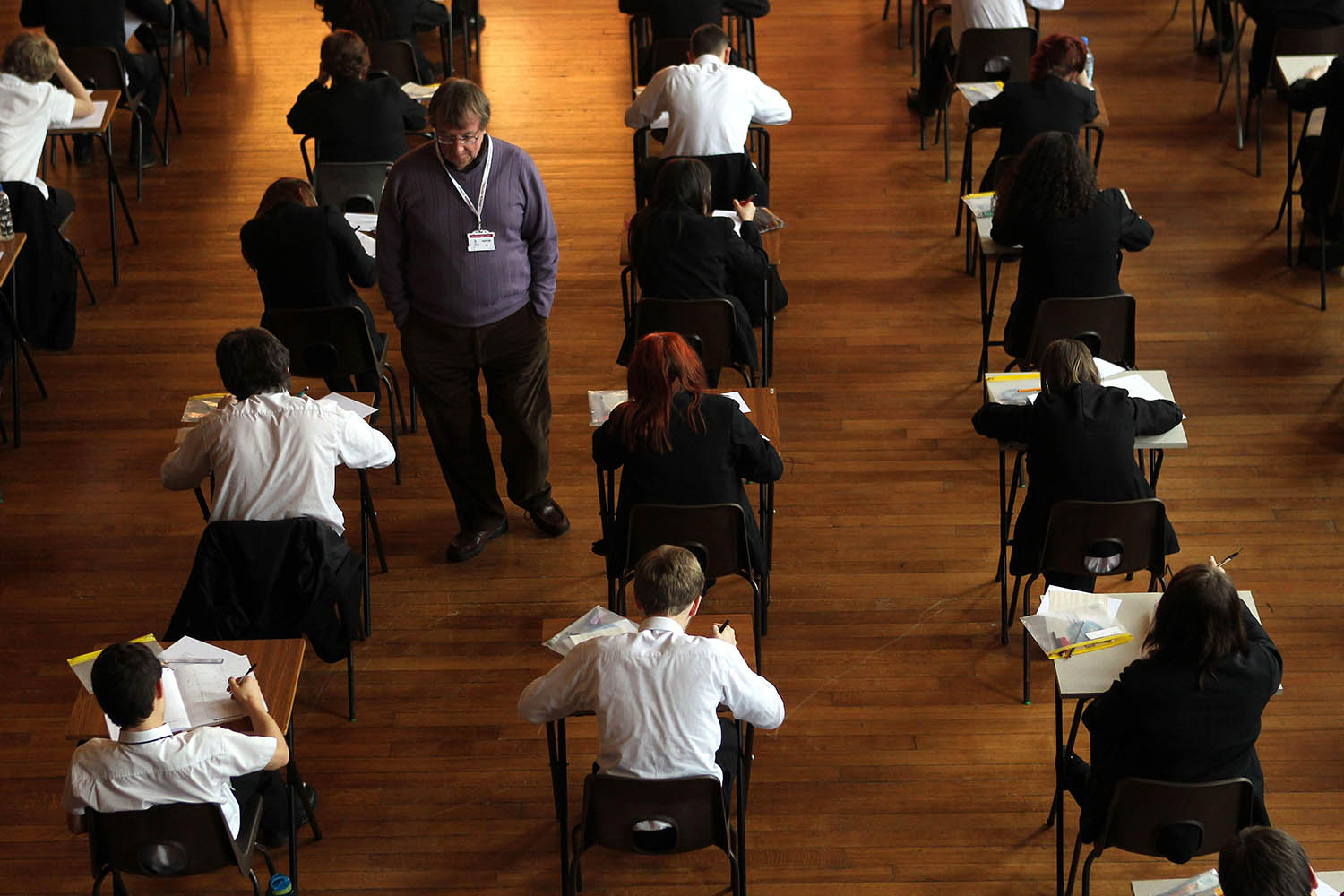

A strategy for white working-class boys will be included in a forthcoming white paper on schools in England that is also going to set out proposals for reforming special educational needs and disabilities (Send) provision. It is part of what is being described in Whitehall as a “reset” of education policy. The question is: how radical are ministers prepared to be? As thousands of children take their GCSEs, senior Labour figures are agitating for exams at 16 to be either scrapped in their current form or drastically slimmed down.

There are also calls for A-levels to be reimagined to allow pupils to take a broader range of subjects up to the age of 18 and end the “sheep and goats” division between academic and vocational education.

Tensions are growing in the government over the future of the curriculum and assessment regime. Becky Francis, the academic appointed to head a review, promised “evolution not revolution”, but some in the DfE and No 10 believe fundamental change is required to create a system that is more relevant and engaging for pupils while better preparing young people for work. One well-connected educationalist describes Francis as a “timid technocrat” who is likely to produce a “damp squib”. Others believe Bridget Phillipson, the education secretary, may be more willing to champion change, particularly to the number of exams children take at 16. “When the review comes back, she could always say: ‘I’ve got this – I understand these recommendations but they don’t go anywhere near as far as I want,’” says a source.

Oli de Botton, the prime minister’s new education adviser, has long called for a complete overhaul of what he sees as a “broken” assessment system. He once suggested that GCSEs and A-levels “neither stretch the brightest very much nor do they provide good opportunities for kids to get decent vocational skills”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Last year he wrote a policy paper on the curriculum for Labour Together, the Starmerite thinktank. It argued for a “broad and bold” transformation of what and how children learn, including a greater focus on creativity, oracy and employability. One idea was a “digital learner profile” which would allow pupils to set out their achievements beyond written exams.

Peter Hyman, who set up the innovative School 21 with De Botton and was an adviser to both Starmer and Tony Blair, believes that an overhaul of GCSEs and A-levels should be “one of the great legacy reforms” of the Labour government. “Preparing young people for a rapidly changing world requires every bit as much radicalism as turning around the NHS,” he says. “It’s only through radical reform that we will get the economic growth we desperately need in all parts of the country and develop the talent to be at the cutting edge of new industries.”

Keir Starmer, whose son took his GCSEs last summer, is said to be personally concerned about the shortcomings of a system that tests children on how well they can memorise facts rather than encouraging a broader set of skills.

Four former Labour education secretaries – David Blunkett, Charles Clarke, Estelle Morris and Alan Johnson – are among those urging him to introduce fundamental reform.

Nobody is suggesting that exams should be abolished altogether but there is a growing sense in Whitehall that the current system is writing off too many children.

Actor Eddie Marsan. White boys who are eligible for free school meals, like Marsan was, consistently underperform in education.

About a third of pupils effectively fail all their GCSEs at 16, and they are disproportionately from the most disadvantaged families. Almost a million young people are not in education, employment or training. There is a mental health crisis among teenagers, and a fifth of pupils are consistently absent from school.

The public is becoming increasingly disenchanted with the disconnect between education and the jobs market. An Opinium poll for The Observer found that only a fifth of people think schools prepare children well for life or work. Just 15% believe assessment should rely mainly on exams.

Employers are desperate for change. A recent survey of 300 businesses by PwC found that only four in 10 think the current curriculum and assessment system prepares young people properly for the workplace. Almost half of companies have to give additional training in computer skills, critical thinking or problem solving to recruits. A third find themselves providing basic literacy or numeracy support.

Since the election, the DfE has often seemed on the back foot. The well-organised defenders of a traditional “knowledge-rich” curriculum, led by the former education secretary Michael Gove, have been quick to accuse the government of “dumbing down”.

The changes to academy freedoms which are currently going through parliament have been attacked by both Blairites and Conservatives for undermining one of the rare cross-party policy success stories of recent years.

To the frustration of ministers, the controversy has made Downing Street reluctant to embark on a wider argument for school reform for fear it could be portrayed as undermining standards. One cabinet member says: “We sit in the opportunity-mission board meetings, and there is lots on welfare, jobs or housing when it should be all about education.”

The Conservatives are fighting hard to defend what they see as a strong record on education, but the reality in schools around the country is mixed. Although England has risen up the international league tables, the overall ranking masks deepening inequalities.

The “disadvantage gap” between rich and poor, which had begun to narrow, is once again growing. According to the Education Policy Institute, poorer pupils are more than 19 months behind their wealthier peers at age 16, and there are enormous regional variations. In Blackpool, the “disadvantage gap” is 28 months, in Knowsley 27 and in Portsmouth 26.

The focus on white working-class boys will be uncomfortable for some on the left who prefer to highlight a simpler connection between deprivation and educational outcomes. The evidence suggests, however, that parental attitudes matter at least as much as family income or what happens in the classroom.

‘A third of the country leaves education without the system finding out what they can succeed at rather than what they can’t do’

‘A third of the country leaves education without the system finding out what they can succeed at rather than what they can’t do’

Anthony Seldon, headteacher and historian

Headteachers describe pupils starting reception still in nappies, unable to talk or speaking with an American accent because they have spent so much time watching cartoons.

“There is something about being clear about the expectations, responsibilities and obligations on families, but we also need to orientate what we do to make schools more engaging, open and inviting places,” according to a DfE source.

Anthony Seldon, the headteacher and contemporary historian, says a radical shakeup is needed to draw out the potential of every child rather than just those who are good at exams. “It would not be dumbing down – it would be levelling up,” he says. “It’s totally unacceptable for a third of the country, including many white working-class boys, to leave education without the system finding out what they can succeed at rather than what they cannot do. It was a failure of the Gove reforms not to address that, and a glaring omission that is contributing to the country’s poor economic performance, as well as causing misery to young people. Labour has to grip this so we can move into a new era. The education system has to change.”

Photograph by PA Images/Alamy