During the closely fought 1992 general election campaign – Major v Kinnock – the main BBC TV news bulletin, which I was editing, ran an item on NHS health budgets (yes, even then). At the end of the programme I trotted back to the newsroom. Two producers held up telephone receivers: one cradling an incoming blast of complaint from Conservative HQ, and one from Labour – about the self-same item.

In a disgraceful act of self-indulgent theatre, and only for a brief moment, I grabbed the receivers, one in each hand, and placed them in a loving embrace, mouthpiece to earpiece for maybe 15 seconds. Only after that did I speak to them in sequence to discover – surprise surprise – that they had nothing of substance to say.

They were going through a ritual, doing what so many have done before and since, in the hope that their accusations of bias would lead to a change in the balance of future coverage. They would not have bothered to phone a newspaper in the same way, because they would have calculated they would have been laughed at. Laughing at complainants is not the BBC way.

For all the decline in its audience numbers, the BBC still matters hugely. In part because it is used more than its competitors by a mile; 94% of the UK adult population per month, and on average 15 hours a week each. It is still the most trusted news brand out there.

But that’s not the only reason politicians feel an insatiable need to burst forth about the BBC’s doings. They can, and do, claim extra legitimacy for their beefs because of their democratic status, while the compulsory licence fee, £174.50, ensures any MP can buttress their running commentary with reference to the interests and opinions of their hard-pressed, licence-paying constituents.

There’s a lot of golden-ageism about the BBC’s impartiality … It’s very largely misguided

There’s a lot of golden-ageism about the BBC’s impartiality … It’s very largely misguided

There are other political forces that bore their way into the BBC. It’s the government that sets the licence fee in the first place, mostly through gritted teeth. It would rather it was funded by something less visible – or perhaps Father Christmas. And it’s the government that, every decade or so, decides the terms under which the BBC operates at all in the form of a Royal Charter. The next one is due in 2027 and nobody has much of an idea as to what is in the government’s head. But it takes up a lot of BBC thinking time.

There’s not much affection to be found anywhere on the political spectrum for the Beeb and, often, that’s understandable. You don’t want the politicians and the largest media organisation in Britain to be hugger-mugger. If you had to choose, friction is much preferable to intimacy.

A host of politicians and commentators forever defer to the memory of the sanctified Lord Reith to add heft to their critique. The latest is Nigel Farage, who in the wake of last Sunday night’s resignations said the BBC should exist but in a stripped back form with no licence fee, and that it “should get back to its Reithian principles” of “political neutrality”. The Times this week similarly advocated “Reithian principles” in its latest editorial (the zillionth) urging the BBC to “reform itself”.

Except that Lord Reith, a borderline monster, was not neutral. During the general strike in 1926 he kept Labour off the airwaves, a risible decision even in a more deferential age.

There’s a lot of golden-ageism about the BBC’s impartiality and its record in telling the truth. It’s very largely misguided. For a lot of my life the BBC has reaped the dividend from an amorphous but strong sense that it had had a “great war”, with its reporting centre stage. It definitely did many marvellous things during the second world war – but for understandable reasons, it was highly constrained. The truth was very, very often not told.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

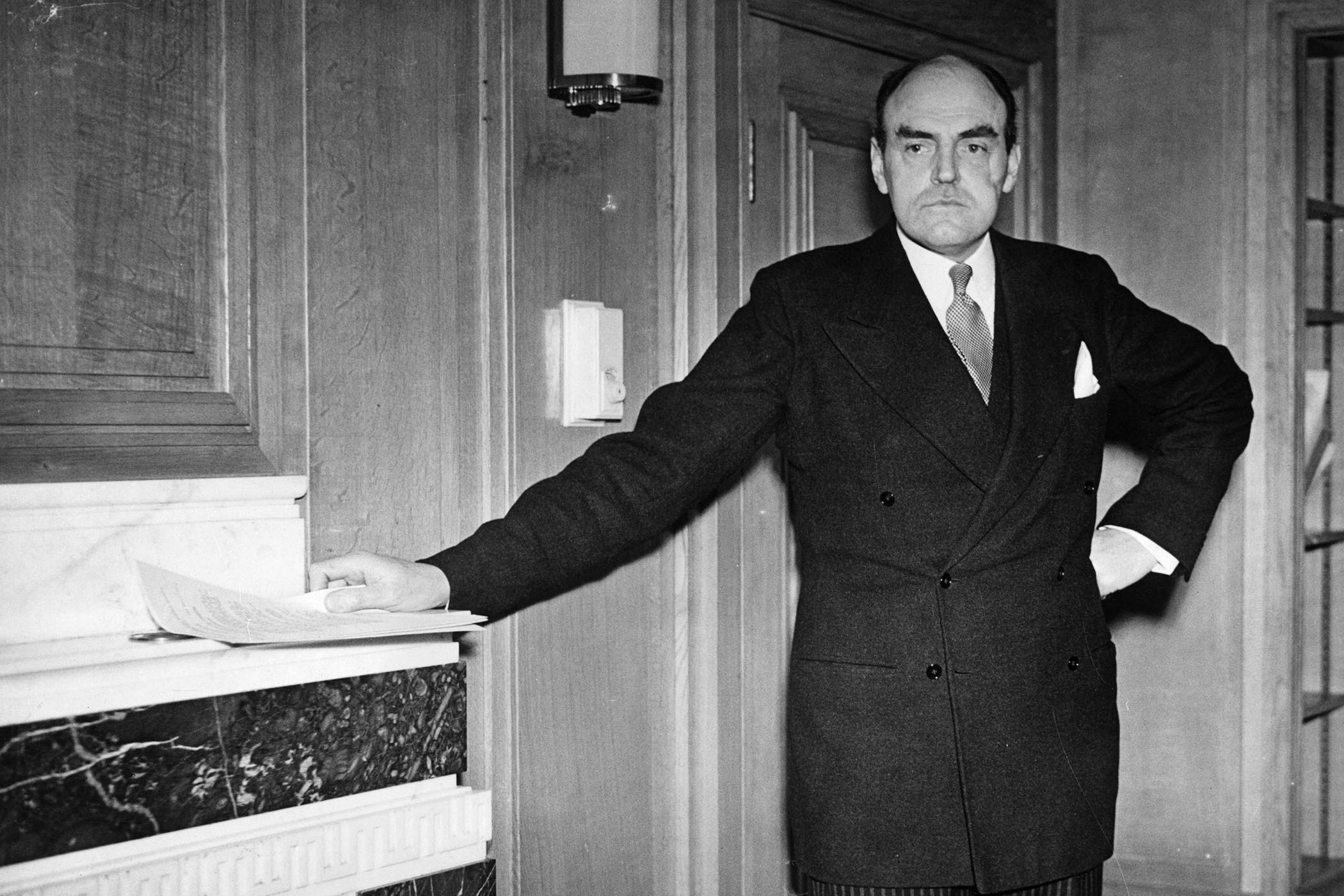

During the Suez crisis in 1956 – not often featured in golden-age accounts – the BBC hummed and hawed before finally allowing Labour’s leader, Hugh Gaitskell, who was bitterly opposed to Britain’s involvement in the war, to address the nation. The prime minister, Anthony Eden, was livid and claimed that the BBC had – what else – acted against “the national interest”.

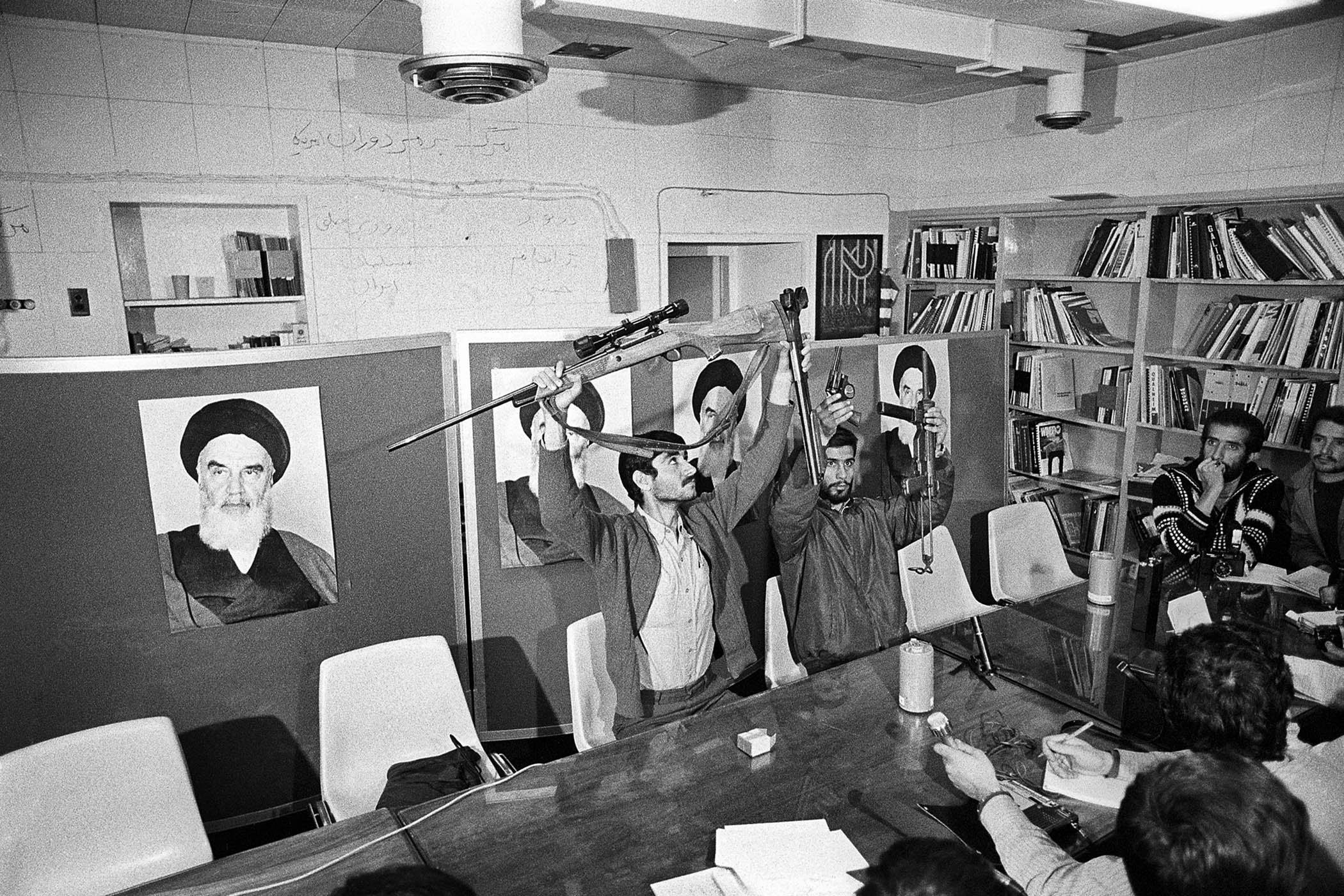

And the rows and the pressure have gone on and on and on. The BBC was accused of treachery during the Falklands war because of the properly inquiring tone of another of its great presenters – Peter Snow. Its reporting of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction – lack of – in 2003 led to a seismic row, the resignation of both the director general, Greg Dyke, and the chair, Gavyn Davies, and a humiliating apology – but the BBC had certainly made mistakes and I should know.

There was no golden age of BBC impartiality, and there has been no golden age of politicians willing strongly to recognise and appreciate, in public at any rate, the BBC’s journalistic integrity. I don’t suppose that will change. In a less shrieky world the departure of the hugely able Tim Davie would lead to some understanding about how tricky it is for a public service broadcaster to navigate the crashing forces of polarisation. Dream on.

Mark Damazer is the former controller of BBC Radio 4

Photo by William A. Atkins/Central Press/Getty Images