A few weeks ago, Sam Freedman wrote in The Observer about the challenges facing the centre right. After listening to hundreds of voters and senior strategists in the US, Germany, Australia and the UK for new research for the Progressive Policy Institute, it is hard not to conclude that centre left parties are facing their own difficulties too.

The findings should make every politician deemed part of the status quo sit up and take notice. You could say it is a plague on all your mainstream parties.

Voters around the world have never been more disaffected, especially those from the struggling working classes. Previously thriving and optimistic that their kids could “better themselves”, many now feel beleaguered; neglected by “tired” political parties that once championed their cause. In Germany, voters asked to imagine the Social Democratic Party (SPD) as a drink chose stale coffee, contrasting with the populist AfD, seen as “an energy drink” , “fresh, ready to provide a much needed shake-up”.

Change is non-negotiable for these voters and there is much talk of delivery. Of course, delivery is non-negotiable too. However, as the Democrats found to their cost in the US, delivery counts for little unless these hard-pressed working-class voters can actually feel it.

Daily battles to make ends meet have pushed the cost of living to the top of their priority list. Immigration is a close second, driven by a powerful sense of unfairness. In the course of our research, we heard the same anger everywhere:

“My son can’t find an apartment but everybody comes pouring in from foreign countries, and they suddenly get an apartment. Something is very wrong,” said one former SPD voter in Germany.

“If you let thousands of people into the country then it’s a problem if they don’t sustain themselves and take the resources of people who have paid into the country their whole lives,” a former Democrat voter in the US said.

However, against this bleak backdrop, we found positive lessons where the centre left has succeeded – in Australia, in the UK a year ago, and in pockets of the US where Democrats bucked the trend and won. These wins weren’t easy. But successful candidates persuaded voters to believe they would deliver for them, because they believed they could deliver for them and, even more importantly, they believed they wanted to deliver for them. This last point is the deal breaker. Not just “yes we can” but also “yes we care”.

Only by feeling political leaders’ conviction as well as seeing their competence was it possible for voters to believe in them. And only when they believed in politicians was it possible to believe in their country, believe in their future, believe in themselves.

Donald Trump ticked the box for voters. Seen as a strong champion, if imagined as a car he’d be a dump truck: as a drink he’d be neat whisky: tough and competent. But he also seemed motivated, successfully channelling working class voters’ anger, overcoming misgivings that he might be ‘in it for himself’ or the rich.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Winning US Democrats acted as local insurgents, battling for local communities

Winning US Democrats acted as local insurgents, battling for local communities

In Australia, Anthony Albanese, like Keir Starmer in the UK, also championed working people. After losing Labor’s lead mid-term, by election day he was “Albo”: down to earth, on your side, fighting for you: “Albo’s a normal bloke you could have a beer with. He gets it,” explained one persuaded voter. His Medicare initiative was a strong symbol of “getting it”. Voters could see much-needed new care centres opening in their own neighbourhoods. This tangible proof point was mentioned again and again by swing voters.

In each country voters spoke with sadness about the decline of town centres. Physical signs of disrepair like boarded-up shops and pot-holed streets were a constant reminder of the neglect that they felt and of government’s inability and unwillingness to change things.

Winning US Democrats had tackled this directly, acting as local insurgents and battling for their local communities. Successful candidates delivered on kitchen table issues and focused their campaigns directly on local people. One confided: “In my district we had Mrs Domico – a single voter that my staff and I kept in our minds at all times.” Another, Michigan’s Kristen McDonald Rivet, addressed voters directly. They liked what they saw: “She wasn’t putting on a façade… it seemed like she was talking to a friend.”

If building belief is the aim, there is a powerful belief bias at play when both delivery and conviction combine to create local champions. Maine’s Jared Golden hired a boat to bring constituents along the river to Capitol Hill, announcing: “Washington wasn’t listening to Maine, so we brought Maine to Washington.” A swing voter observed: “Golden had the whole community behind him. It felt authentic. It felt truthful.”

Building back belief in government can be done. But it means showing and telling the difference being made by politicians who care and can do. Being in power at virtually every level in the UK is a huge advantage. It’s time to use it.

Deborah Mattinson was appointed director of strategy to Keir Starmer in July 2021 and helped deliver electoral success three years later. Claire Ainsley is director of the centre-left renewal project at the US based Progressive Policy Institute

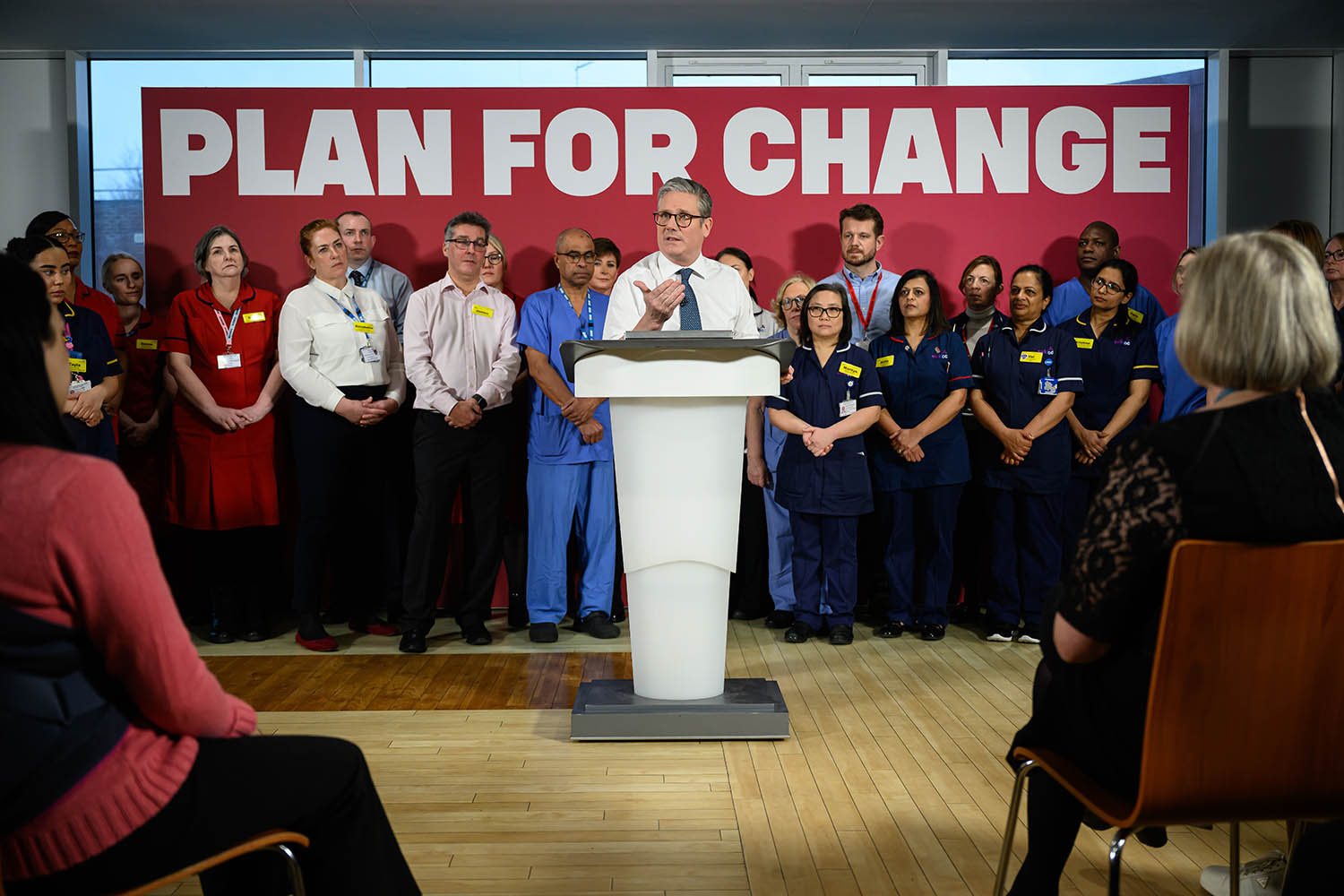

Photograph by Leon Neal/Getty