Latin America has never been a priority for British intelligence. That was all too clear back in 1982 when Argentina seized the Falkland Islands with little warning.

MI6 operates relatively few stations in the region and GCHQ leaves most of the work of intercepting communications to the Americans.

There are operations in Colombia and the Caribbean for countering the drugs trade. Some of the sharing with the US over this work was suspended late last year as Washington began striking Venezuelan drug boats amid concern that British military and intelligence officers could become complicit in war crimes. But the reality was that this kind of intelligence – information about speedboats moving around the West Indies for instance - was low level and of marginal value to the US.

The US did not need any UK help – militarily or intelligence-wise – to carry out the operation to capture Maduro. This was America first and America alone, a display of power when it comes to intelligence and military force even if the political aftermath is uncertain. But even if the UK played no role, the implications of that operation for London and British intelligence services are profound.

Other countries' intelligence services will be scrambling to work out what all of this means, perhaps none more so than the spies of Beijing. A senior Chinese envoy was meeting Maduro just hours before he was taken by US special forces. Not only did Chinese intelligence fail to foresee the US plan but they now look to have lost a crucial foothold in Latin America. Venezuela was Beijing’s most important ally in a growing tussle to assert influence in the region. As well as growing commercial sway and using debt for leverage, Beijing has been quietly expanding its military and intelligence footprint across the region from Venezuela to Argentina (where it has a space tracking station) to Cuba (where it has listening stations).

This increasing Chinese influence was one reason Washington was keen to act. The original Monroe doctrine of 1823 sought to keep other powers out of America’s backyard. In those days that meant European powers like Britain and Spain in Latin America and Russia in the Pacific north-west of the continent. The modern “Trump corollary” to that doctrine is more about pushing China back. The traditional response to such worries might have been to try and win over Latin American countries with economic ties, diplomacy or development aid. But instead the Trump administration elected to take a very different tack; to get rid of a leader cosying up to Beijing and make clear that this is just the start of a new kind of coercive diplomacy which will stretch across the region. In response, China, like Russia, has done little to suggest it will do much more than offer bland statements about the removal of an ally.

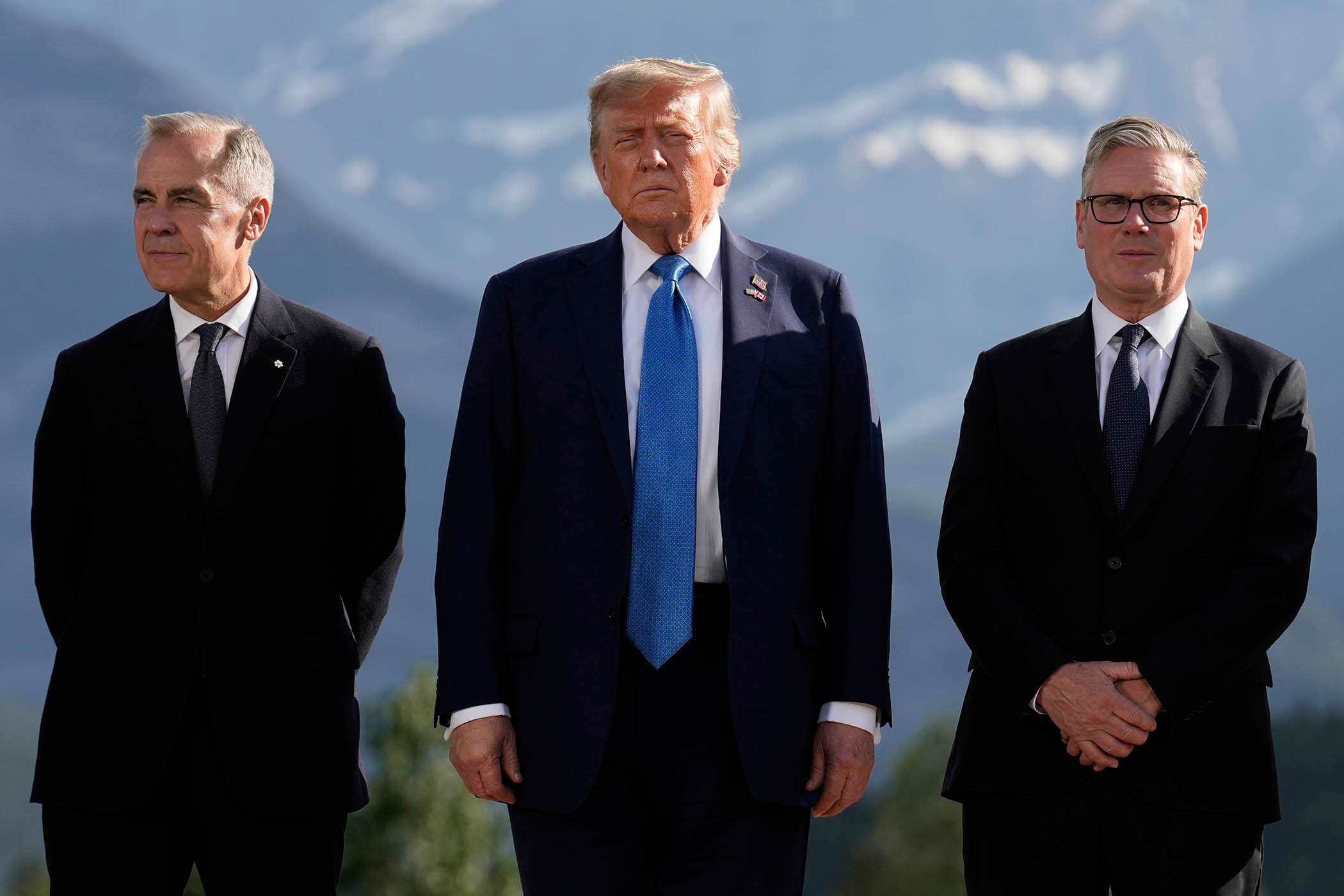

For Britain, an aggressive American push-back against Chinese influence poses problems. Keir Starmer is expected to visit Beijing shortly in an effort to improve relations. Washington will be watching closely – but British officials know that the US is also looking to reset economic and trade ties with China so they will be wary of being caught out.

Even if Britain’s direct interests in Latin America are relatively narrow, the new Trump ‘Donroe doctrine’ has implications which reach its shores

Even if Britain’s direct interests in Latin America are relatively narrow, the new Trump ‘Donroe doctrine’ has implications which reach its shores

There has even been speculation that China might secretly welcome the move by Trump because it would make it easier for China to justify a move against Taiwan. In truth, Beijing sees Taiwan as an internal issue and will ultimately make a judgement primarily on the criteria of whether it is militarily ready to take Taiwan and whether the US would respond. But other countries in Asia may still be left nervous by the possibility that larger states will feel they have a freer hand when it comes to smaller ones.

The problem for Britain is that even if its direct interests in Latin America are relatively narrow, the new Trump ‘Donroe doctrine’ has implications which reach its shores. That is particularly thanks to the northern rather than southern part of America’s backyard. Canada is not going to be invaded or see its prime minister snatched from his bed, but American assertiveness has already put pressure on the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance of English-speaking nations of which the US, UK and Canada are part. It has been a central pillar of British intelligence since the end of the Second World War but has already been entering a more complex phase with sub-arrangements like the AUKUS alliance of Australia, the UK and US. The relationship between the US and Canada over tariffs has at some points spilled over into talk of undermining security relationships. They have yet to break down but the old cosy Five Eyes meetings are going to be a thing of the past.

Greenland presents the biggest headache for London. Britain has reinforced the strong talk from Denmark – which runs the territory – that Washington should back off its claims that it wants to take over. That is in response to President Trump reiterating his talk that the US needs Greenland for its security. Specifically, he has cited claims that Russian and Chinese ships are operating there. There is not much evidence of that in Greenland though it is true that both Russia and China are becoming more assertive in the Arctic generally, sending submarines under the ice and trying to build economic ties. Beijing has certainly been interested in Greenland’s critical minerals and in the eyes of hawks in Washington, having more control over Greenland is a pre-emptive move to stop a more independent-minded Greenland turning away from Denmark and towards China and its investment.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

But Washington’s talk of taking control of the territory undoubtedly risks straining the NATO alliance to breaking point. If a country outside the alliance was publicly threatening to take Greenland it would trigger talk of Article Five and collective self-defence but no one in NATO has any clue how to react when the threats come from within.

Similarly, if any other country was behaving like Washington recently, a top priority for the spies of other nations would be collecting intelligence about the intentions of its leadership. That is a no-no for Britain, as under the Five Eyes arrangement members are not supposed to spy on each other. Former British spies say there is nothing to gain and a lot to lose from even thinking about spying on Washington, since being found out would be disastrous. They remain confident that the US is keeping, and will keep, its side of the bargain as well.

Even an operation as unorthodox as the capture of Nicolás Maduro will not trigger a change in that UK policy, particularly since intelligence collection on Washington’s intentions is barely needed anyway, when officials and influential Americans openly telegraph their ambitions and boast of their intentions over social media, posting pictures of Greenland covered by an American flag.

On an operational level, British spies may still be working effectively with American counterparts in many regions of the world like the Middle East. But in the wake of Venezuela, the strategy of staying close while keeping their heads down and hoping the storms will pass looks like it will get much harder. And the UK may have to find a way of keeping a closer eye on what is going on across the Americas than it has done in the past.

Photograph by Mark Schiefelbein/AP